Higher education is a battlefield and the trauma inflicted in this war of inequitable attrition can leave lasting effects that compromise and exhaust mental well-being.

While all mental health is undeniably important, a context that receives little attention is how black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) staff experience mental illness in the face of continuous racial inequality and discrimination within the academy. This takes covert and overt forms, including lower wages, being undermined by colleagues, and hiring biases.

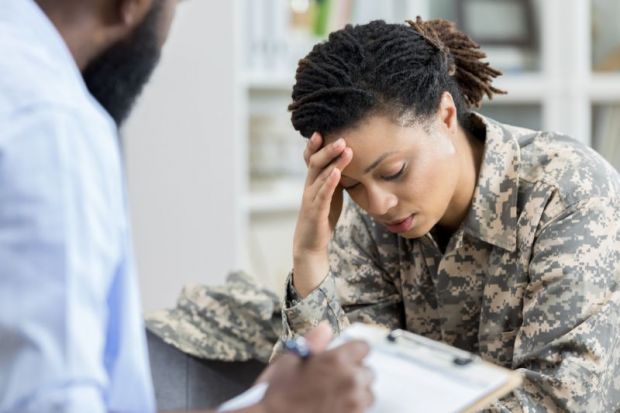

This type of visceral violence places many academics of colour in positions of vulnerability. Often, appropriate psychological interventions are not available for staff who encounter racism in all its sustained forms, and racial micro-aggressions resemble a death by a thousand cuts, which invariably has consequences for BAME staff.

Currently, university pastoral services are inundated with staff referrals to counselling services, with occupational health services equally severely under strain. While there has been much needed focus on student mental health, concerns about the mental health of BAME staff within higher education remain in the margins. There is little acknowledgment of the racialised terrain of the academic workplace or the fact that these experiences are compounded by a sense of victimisation, marginalisation and racial discrimination.

In many cases, universities are complicit in sustaining and maintaining the discriminatory cultures that so often disadvantage BAME staff. Racial harassment, barriers to promotional opportunities and career advancement, and the dearth of BAME senior leaders within the sector are all significant factors. The relentless, daily encounter with racial discrimination is a nuanced and complex experience that requires contextual psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing.

But many BAME staff with symptoms associated with mental illness have had unfavourable outcomes from mental health intervention. Often their experiences reflect an attempt to dilute the perniciousness of racism, probably, in part, because of the lack of diversity among healthcare professionals within higher education pastoral services.

Indeed, racial ascriptions and conscious or unconscious biases can emerge when healthcare professionals probe, and can lead to attempts to decentre racism as the problem. This trivialisation and deflection has huge implications for BAME staff seeking psychological help.

Likewise, the racism that they experience recounting racialised episodes to colleagues, line managers or mental health professionals can be traumatic.

To address the gaps in adequate support for BAME staff, pastoral and counselling services on offer must be culturally appropriate, where necessary, and recruitment processes for healthcare professionals within universities must require cultural sensitivity as an essential component of their skill set.

Healthcare professionals should also undertake continuing professional development that supports them in understanding various types of intersectional discrimination and how these affect minority groups more specifically within the higher education sector.

Understanding the plight of BAME staff is important for the higher education sector’s wider goal of creating greater equity for ethnic minorities.

Part of the solution is developing institutions that are culturally representative in terms of race, class, religion, gender, sexuality and ability. Pastoral services comprising ethnically diverse healthcare professionals will recognise the need to cater to a diverse university populace.

This would also contribute towards a greater understanding of the extent of racism in higher education and its debilitating and sustained effect on BAME staff.

Jason Arday is assistant professor of sociology at Durham University. He is also visiting research fellow in the Office of Diversity and Inclusion at Ohio State University and a research associate in the Centre for Critical Studies in Higher Education Transformation at Nelson Mandela University.

Dr Arday will be speaking at THE Live, a two-day event exploring how UK universities can renew their public sense of purpose and tell their story to the world, running from 27-28 November.