This week, an Advertising Standards Agency crackdown on deceptive claims by universities identified several institutions that it believes have misled students.

Chief executive of the ASA, Guy Parker, said that the rulings send "a clear message to UK universities" about backing up claims "with good evidence" . "Misleading would-be students is not only unfair, it can also lead them to make choices that aren't right for them," he said – and quite rightly.

When it comes to student recruitment, we believe medical schools advertise inappropriately too. Below, we look at several areas where we believe this is happening.

Medical schools’ use of league tables

When considering to which UK medical schools they should submit applications, would-be medics have three well-known domestic guides available to them. Two are free of charge online (the Guardian University Guide and the Complete University Guide), and another is available for purchase (the Times/Sunday Times Good University Guide). These guides present league tables that, as we know from personal experience and from perusal of student websites, are likely to influence applicants’ choices.

Universities use these league tables in their advertising. “Dundee – 1st in Scotland” trumpets that medical school’s website, quoting its position in the Guardian league table. But it is also 4th in Scotland in the Times’ league, and 5th in Scotland in the CUG’s table (and there are only five schools in Scotland).

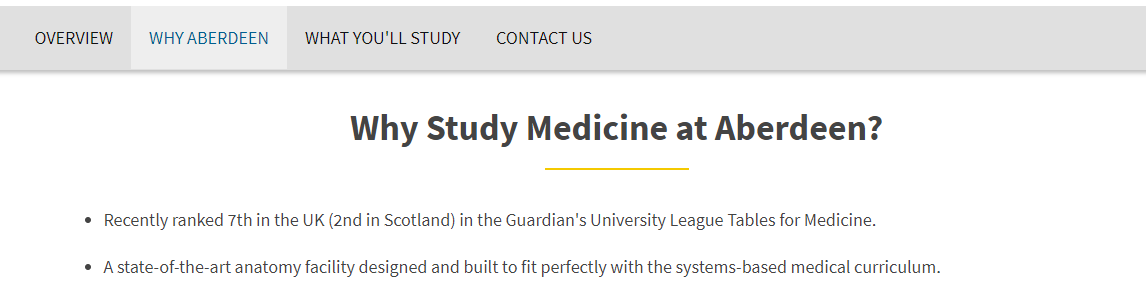

Meanwhile, the University of Aberdeen’s current claim (“recently ranked 7th in the UK (2nd in Scotland) in the Guardian's University League Tables for Medicine”) is quoting the 2017 guide data. The 2018 guide (published in May 2017) has Aberdeen 12th in the UK and fourth in Scotland. It is 25th in the UK in the 2018 CUG.

Interestingly, none of the domestic UK rankings and the associated guides incorporate the actual performance of graduates from different medical schools in their later postgraduate training.

This information is readily available from the website of the UK regulator, the General Medical Council, which publishes a variety of datasets that can be explored to examine the performance of graduates of different medical schools on all postgraduate examinations and progress reviews.

Incorporating career performance data

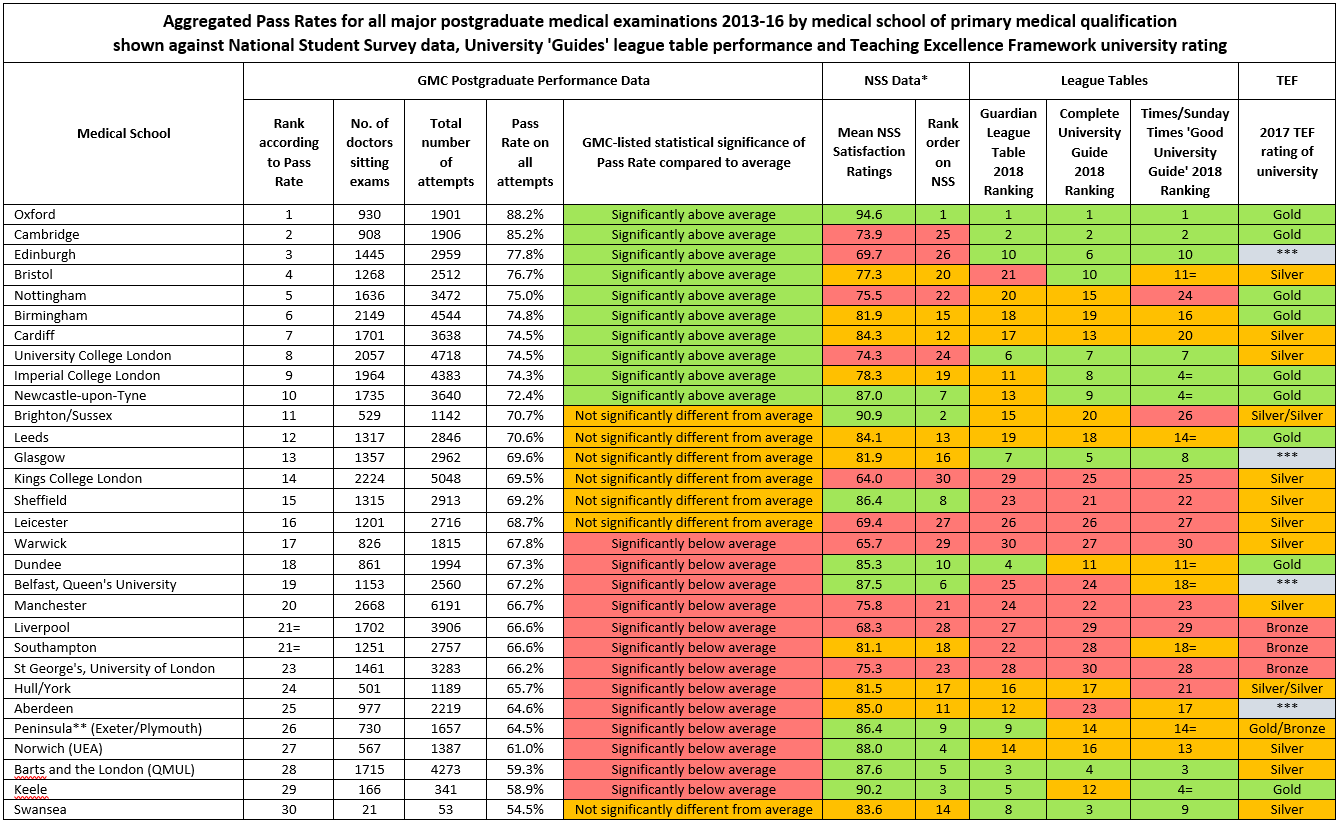

Believing that it may provide more sensible guidance for would-be doctors, we have prepared a league table based on graduates’ published examination performance:

Table notes: 1. GMC data for rump 'University of London' graduates (N=448) excluded as medical school is unknown. 2. St Andrew’s - not a complete medical school - is excluded from the above, as are Lancaster and Buckingham medical schools, whose students have yet to take postgraduate examinations. Where necessary, guides’ league tables have been adjusted as a consequence.

* 2016 NSS data are shown: the 2017 data published recently are incomplete because of student boycotts ** The GMC provides data for Peninsula Medical School graduates, but it is now separated into Exeter & Plymouth Universities. Figures in 'guides' and NSS columns are the two universities' averages *** Declined to participate in TEF exercise Download a larger version of this table

As well as examination performance, the table above shows performance of the 30 full medical schools on the three guides’ latest league tables, the top and bottom 10 schools on each guide being marked in green and pink respectively. The guides are clearly somewhat discrepant, with one school ranking fourth in one, and 13th in another; and another school at rank 10 in one and rank 21 in another.

The table also shows aggregate National Student Survey performance, and the universities’ performance in the recent teaching excellence framework (TEF).

Ranking of postgraduate performance does not relate significantly to ranking on the three league tables – confirming earlier findings. There was, however, a significant correlation of postgraduate performance with university TEF score (although the TEF measure is not specifically for the medical school but the whole university).

Our table does not include average academic attainment of entrants, nor the amount of assessment within medical schools, although both of these also correlate independently with better postgraduate performance.

Differential performance of medical schools’ graduates is also relevant to the planned expansion of medical school places, envisioned as an allocation of 1,500 extra places by 2019. Expanding schools whose graduates’ career performance is poor might extend the workforce in a less than optimal way.

Perfidy among the Mediterranean franchises

UK medical school expansion is not limited to the home country. Two UK medical schools have recently established Mediterranean franchises reminiscent of the Caribbean offshore schools that have attracted considerable criticism for their marketing practices.

Barts and the London Schpool of Medicine and Dentistry (Queen Mary University of London) has taken full-page newspaper advertisements touting the benefits of students entering their school on the Mediterranean island of Gozo. “Barts and the London, QMUL is ranked 2nd in the UK for medicine,” it states, referencing the Guardian University Guide 2017.

The advertisement offered a picturesque sea and harbour view, but did not mention that Gozo has a population as tiny as that of Rutland – which may be relevant to the effective provision of a comprehensive undergraduate curriculum.

As for "student life", however, its prospectus promises much: “From prehistoric temples to world-class scuba diving facilities and watersports, clear blue seas and white sandy beaches, festivals and football, there’s plenty to see and do here... Living here will be an unforgettable experience”.

The prospectus also describes Barts as “one of the top medical schools in the UK” but does not tell would-be applicants that that postgraduate performance of Barts’ graduates is the worst of those of all well-established UK medical schools (see table).

St George’s Nicosia operation, meanwhile, recently advertised in its prospectus that its mother school “…is recognised for excellence in medical education, receiving a score of 23 out of 24 in the UK’s Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) inspection of medicine – the highest score of any London medical school”. Enquiries to the QAA and others showed that this information was nearly 20 years old, based on the Teaching Quality Assessment (TQA) last published in 2000.

It was subsequently withdrawn, the mis-sell being blamed on the Cyprus operation, even though the QAA reports that St George’s signs off all recruitment material.

In conclusion, we think it is wrong that, in their recruitment processes, scientific, evidence-based institutions cherry pick statistics from guides that rank schools quite differently from each other. We urge those contemplating a career in medicine to both to examine the GMC's dispassionate data which describe graduates' performance in later examinations, and to treat NSS and university guide data with caution.

Aspirant doctors contemplating entry to UK offshore schools (which demand heavy fees of up to €175,000 over five years) should probably treat marketing claims with particular scepticism. Those charged in the next few months with deciding to which schools to allocate the 1,500 extra medical school places, to which Jeremy Hunt committed, should also note those data similarly.

Richard Wakeford is life fellow of Hughes Hall, University of Cambridge, and Chris McManus is professor of psychology and medical education at UCL.