On 12 January, the Higher Education Committee (HEC) of the University and College Union (UCU) must make a crucial decision. Will it implement the plan it voted for in November and begin a marking and assessment boycott (MAB) this month – before, in February, calling UCU’s 70,000 members across 150 universities out on indefinite strike until UCU’s pay and pensions demands are met? Or will it adopt a new course?

UCU’s general secretary, Jo Grady, has proposed an alternative approach that would see escalating strikes through February and March, then a re-ballot and a MAB targeted at end-of-year assessments and, potentially, indefinite strikes over the final months of the academic year.

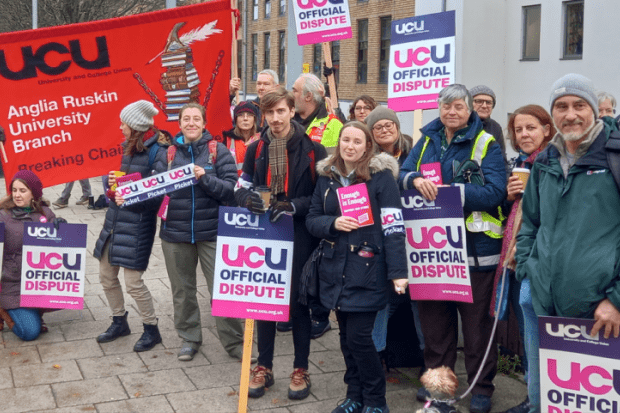

UCU’s historic success in winning an aggregated national ballot for industrial action even with the new 50 per cent turnout threshold has already concentrated employers’ minds. They have brought forward negotiations for the 2023-24 pay round by three months and are willing to consider a pay rise in February in addition to the standard September in return for agreement that neither side will escalate action while talks continue. It was against this backdrop that Grady’s proposal emerged, but it has sparked accusations of betrayal from some UCU activists and heated discussion of strategy.

Supporters of the HEC’s November decision have called for its implementation, demanding that union democracy be respected. Yet members have never been asked about indefinite strikes, and if the HEC acts without majority support, it could not only doom the current campaign but also lead to a mass exodus from UCU, dramatically weakening it.

Grady has asked UCU branches to canvass members and report on their preferences at a meeting on 10 January (two days ahead of the HEC meeting). Do they want indefinite or escalating strikes? Is a MAB starting in January better than one targeted at summer exams (subject to a required re-ballot)?

Meanwhile, at least two other significant pitches have emerged. The “UCU Commons” group favours Grady’s escalating strikes but support a January MAB, while another group led by Sarah Joss, Heriot-Watt UCU vice-president, and Vicky Blake, the former UCU president, modifies indefinite strikes to, perhaps, allow members some respite from deductions: four days of strikes and one day of work rotating each week.

Those favouring indefinite action argue that UCU should make the most of its current ballot mandate and join railway, NHS and postal workers to maximise pressure on employers. They also cite successes arising from indefinite strikes by precarious US university staff at The New School and Columbia University, as well as by UK criminal barristers.

Yet the barristers only opted for indefinite strikes near the end of their six-month ballot mandate and after five months of escalating action. And even industries with much higher unionisation (and, therefore, more union power) than academia have stopped short of such a step. How many UCU members will be prepared to strike indefinitely and lose weeks of pay amid a cost-of-living crisis? With a turnover of around £22 million and a fighting fund of £2 million to £3 million, the UCU could only provide daily strike pay of £50 to £75 for a matter of days. Indefinite strikes risk dividing the union as members who cannot afford to lose pay opt to cross picket lines or quit the union.

The timing of an MAB and its pairing with strikes is crucial to success. Those arguing for an immediate boycott reiterate that it requires no re-ballot, while combining it with indefinite strikes pre-empts punitive pay deductions from employers. However, most December marking will already have been completed, not all universities have January assessments, and those that do will feel little immediate pressure since graduation and progression are decided at the end of the academic year.

In addition, since not all UCU members are involved in January marking and some are more able to afford punitive pay deductions than others, an immediate MAB risks dividing members as well as exhausting strike support funds even before any strike action resumes.

These factors pose huge risks for the UCU. If intensive action occurs too early or for too long, employers may be able to sit back, pocket pay deductions and wait for hardship and division to collapse the strike. UCU Commons’ call, meanwhile, for both January and summer MABs risks satisfying advocates of neither indefinite nor escalating strikes. Moreover, MABs and the indefinite four-days-a-week strikes advocated by the Joss-Blake group are high risk since both could incur pay deductions of up to 100 per cent as employers can legally refuse to accept partial performance.

The questions facing UCU members therefore boil down to this. Should an MAB and strikes begin immediately, raising the stakes for employers and union members and potentially jeopardising current negotiations? Or should the HEC choose Grady’s more gradualist strategy and, like most other unions, put mounting pressure on employers while requiring less sacrifice by members – coupling this with the threat of a re-ballot and summer MAB targeting students’ graduation and progression?

Employer leaders will take full advantage of continued attacks on Grady and prolonged infighting among activists. Therefore, a clear decision that guarantees the support of all UCU members must be made on 12 January. In our view, Grady’s strategy is the most robust one. It will allow wide participation while giving time and scope for negotiations without risking everything on one throw of the dice.

Jak Peake is senior lecturer in the department of literature, film and theatre studies at the University of Essex, where he is also branch president of the University and College Union. Adam Ozanne is honorary senior lecturer in economics at the University of Manchester and a former member of the HEC.