The hullabaloo over the BBC salaries continued this week as Radio 4’s Women’s Hour host Jane Garvey galvanised 45 of her female colleagues at the BBC into writing to director general Tony Hall to insist that the corporation address the gender discrepancies highlighted within it. Good on her. But this got me thinking about the similarities within our own sector.

As a publicly-funded body, the BBC was compelled to publish the salaries of those of its employees paid more than £150,000 directly from the licence fee; effectively, from public funds. So where would this leave institutions like ours? If the salaries of senior academics and officers across the UK’s HEI’s over the £150,000 threshold were published, would our gender pay gap make for any more comfortable reading, and if not, does that necessarily mean what it appears to?

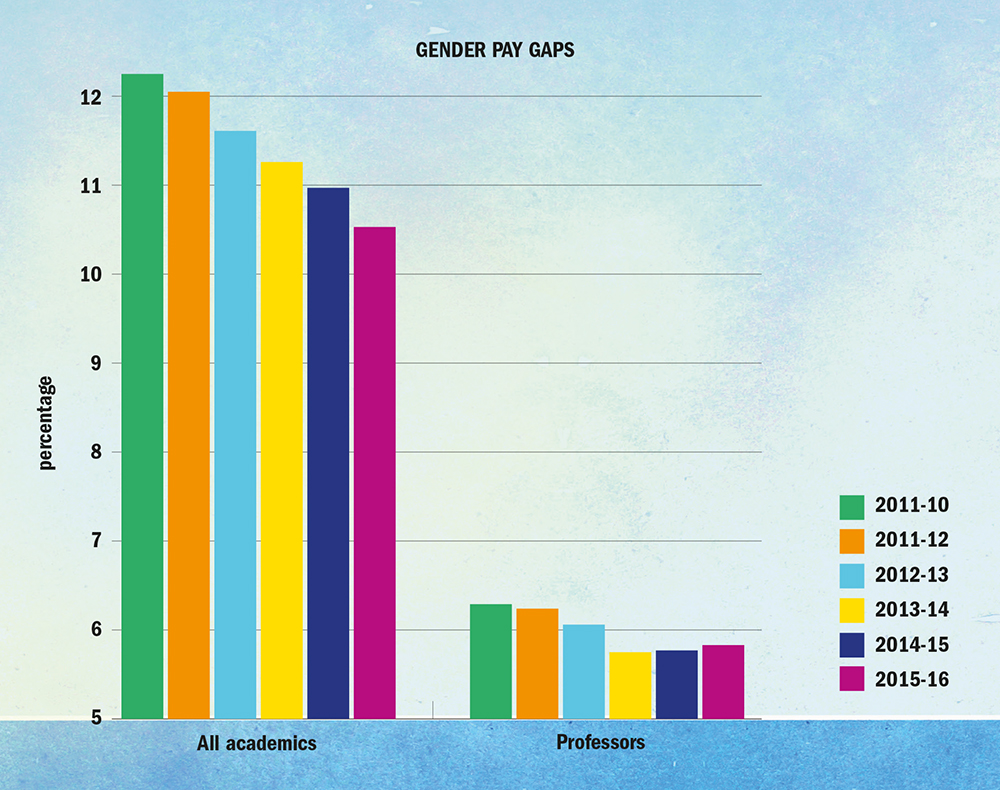

Looking at the figures in the most recent THE Pay Survey, the gap between male and female academics is still eyebrow-raising; a gap of 10.5 per cent in 2015-16, meaning that the average female academic’s salary is less than 90 per cent of her male counterparts'. Not quite as dramatic as the Beeb perhaps, but significant if you’re on the wrong side of that gap nonetheless.

However, while in isolation that might seem pretty damning, viewed over time there’s definite evidence that progress is being made; that 10.5 per cent gap has improved each year, falling continually from 12.3 per cent in 2010-11. And there’s the first problem: at best, one set of published figures is only going to show a snapshot, rather than the trend.

And that trend is positive; pay inequalities across the sector aren’t news to us. Universities are already working hard to address this, but it’s more ‘water on stone’ than an overnight fix. Indeed, it’s entirely possible that measures to remedy the disparity are exacerbating rather than alleviating the problem, at least in the short-term; there’s more than one example of institutions taking positive steps to encourage female academic staff to apply for promotion, which in turn has a negative impact on their academic pay gap due to the larger number of female staff at ‘entry level’ salaries below the average of their longer-standing (male) colleagues.

That will settle down over time as staff turn-over evens out the gender balance and all those new professors progress up the increments, but it could be misinterpreted, if viewed only from an isolated statistic, to be evidence of an increasing problem rather than a positive step towards balancing the numbers.

There are historic issues related to subject area, too. Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa) from 2014-15 estimating academic populations shows a relatively well-balanced 55:45 ratio of men to women in humanities, arts, business, and politics, but closer to an 85 per cent bias towards men in engineering, chemistry, and physics. That’s not going to be resolved overnight, and relies on career and course options in schools being given an equally well-balanced portrayal to boys and girls.

I’m not sure Tom Chambers’ comments helped, either. Essentially, the Casualty heartthrob suggested that men get paid more than women because “men’s salaries aren’t just for them but for their [stay-at-home-mum] wives and children too”. Thanks for that, Tom. But as behind-the-times as that might be, it’s akin to the “women take time out to have babies” argument: it’s true, certainly, that if one really is “only as good as your last paper” then career progression might be hampered by publication gaps due to periods away for childcare, but with the introduction of shared parental leave and flexible-working legislation, this should become progressively less of a barrier than it perhaps once was.

Was it ever entirely true anyway? I know of very prolific grant-and-publication-achieving female academics (with children), and equally some men who seem to survive quite happily on one programme grant per quinquennial.

To take an example close to home, the success rates for men and women applying for grants from the Medical Research Council in 2015-16 actually show a marginally higher percentage success rate for women (25.6 per cent) than men (23.2per cent), and an even 27.5 per cent success for both genders across the five years from 2011/12. What they do show, however, is a far higher number of applications (65.8 per cent), and hence awards, to men than women (3,275 vs 1,615 in 2015/16).

Is this indicative of a smaller number of eligible female researchers (the Hesa data would seem to imply not), or that women are less likely to (or less likely to be encouraged to) put forward funding applications in medicine?

Again, universities and funders are already taking steps to address this. Tying National Institute for Health Research funding for medical schools to Athena SWAN status, for example, might have been a pretty blunt instrument, but it provided levers which universities could use to push for change where attitudinal inertia might otherwise have held back progress.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m certainly not advocating quotas or positive discrimination at recruitment – and I know a number of my female colleagues who would never forgive me for any implication that they weren’t more than entirely capable of competing on a level playing-field without such artificial "assistance" - but increased mentoring and support for more junior "early career" academics, the shifting of meetings from first- or last-thing to more "childcare-friendly" hours, flexible or remote working arrangements, increased nursery provision or tax-saving voucher-schemes, "return-to-work" support for research and teaching staff, gender-blind recruitment processes, and greater outreach to schools and colleges to break down the perception of “boy jobs” and “girl jobs” (thanks, Theresa) are all positive initiatives which we’ve all been working with for years.

Which brings me back to Garvey’s letter. Why just Women’s Hour, or even just the BBC? Surely, in the second half of the second decade of the 21st Century, we should be taking the opportunity to push for wage equality across ALL public sector pay?

Universities lead the way, and while no-one’s suggesting the problem of salary inequality is already magically resolved (it clearly isn’t) we seem to be much more cognisant of the issue, and proactive in challenging it, than we sometimes give ourselves credit for. Whilst complacency or self-congratulatory back-patting would be premature, put simply we just need to continue pushing with the good work and maintain that momentum; keep calm and carry on, indeed.

Alex Holmes is head of administration and finance in the department of paediatrics at the University of Oxford.