The recent debate in Times Higher Education over the merits of pedagogy highlights the sad fact that teaching and learning within universities sometimes feels like a turf war between academics and those in education development.

In recent years, the UK has placed greater emphasis on teaching quality through the introduction of the teaching excellence framework. Alongside other developments, such as the largely mandated implementation of lecture capture, this has understandably led some academics to resent what they regard as unwarranted interference in their teaching and an erosion of their autonomy.

The education development field can often feel similarly embattled. Its credibility and its value are regularly questioned and it can sometimes feel a bit lost and peripheral, desperately trying to gain an academic and institutional foothold. And while the divide between education specialists and those who teach may have reduced somewhat during the pandemic, it is still a divide. The relationship is still dysfunctional.

The hard work of everyone who contributed towards ensuring the continuity of learning and teaching during the pandemic should be celebrated, but we should also recognise that the experience has highlighted that, organisationally, reflection and improvement are needed – when the time is right.

I would argue that the pandemic has underlined that the current model of university teaching is too solo mío (mine only) and that education support is far too disconnected and, at times, esoteric to meet the challenge presented by the greater complexity of present and future technology-mediated learning experiences.

Teaching – irrespective of your disposition towards it – has been burdensome during the pandemic. Academics have largely struggled alone to engage students at a distance or to review hours of video for the purposes of captioning. It is simply not sustainable or effective to add more and more burdens to the academic role and expect people to be able to give their best and not suffer from burnout.

Equally, in order for teaching and learning to be well supported, we need to carefully reconsider the wisdom of centralising teaching support and educational development. Centres for learning and teaching have a very positive mission but they can sometimes feel distant from the real action, contributing to the impression that educational development runs in parallel to teaching and learning as an optional extra.

The perennial issue for education development is getting people other than the usual suspects to engage. For some academics, any advice on their practice will always feel like an irrelevance and affront to their autonomy. However, what I often hear is that academics just don’t feel that the educational development available at their institution offers them real value and meets them where they’re at. There are valid criticisms of disparate one-off workshops that float above the realities of particular disciplines, or of teaching-development programmes that lack cohesion or are more philosophical than practical and focus too heavily on “administrivia”, particularly in relation to technology.

Education development activity can also fall into the “surrogation snare” that is already prevalent within higher education, whereby metrics such as the number of people gaining teaching certification or the scale of improvement in the National Student Survey become the objective, even though they are not necessarily good proxies of teaching excellence.

For education development to be more effective, the system and culture need to change. There needs to be closer collaboration and partnership baked in between educators, education specialists and related professional disciplines. This is where we can learn much from the sometimes maligned world of online education.

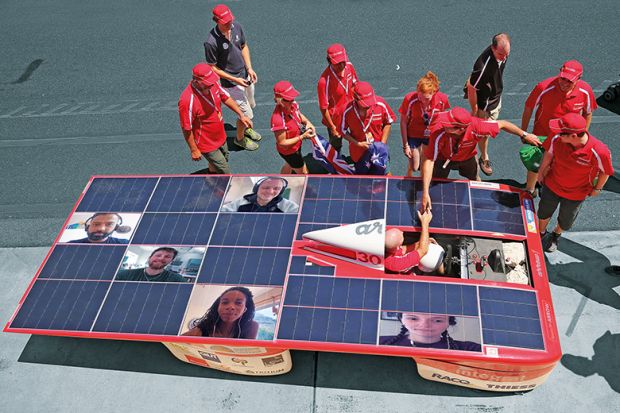

As many have found during the pandemic, teaching online is in no sense easier or less work than teaching in person. But, at its best, delivery of online education is a team sport, with academics and subject-matter experts working in partnership with professionals such as learning designers, developers, producers and project managers to shape and deliver experiences.

This kind of partnership and collaboration often leads to great strides being made in teaching practice as it necessitates reflection and justification of design decisions within a culture of constructive dialogue and debate that involves others.

Regardless of their view on education development, why would academics not want to work as a part of a team with a range of specialisms, pulling together to share the load and craft the best teaching and learning experience possible? Why would they want to bear the whole burden alone?

And why would those in educational development not want to work at the coalface of the educational experience, directly influencing delivery of specific courses, rather than at a distance?

For institutions, the question is simply this: are you set up to enable your people to deliver the best educational experiences? If education institutions are to successfully meet future challenges, teaching and education development need to be organisationally interwoven – not divided and battling for territory.

Neil Mosley is a digital learning consultant and designer working within higher education.