Co-creation of curricula with students: a case study

Eric Tsui outlines a method he uses to enhance student learning through the co-creation of new scenarios for curriculum development in their discipline

Students have to deal with a fast-changing, increasingly complex, globally connected society. Much of what we teach in a curriculum can quickly become outdated. Academics should therefore not be the only group to design a university syllabus or curriculum and students’ contributions are crucial.

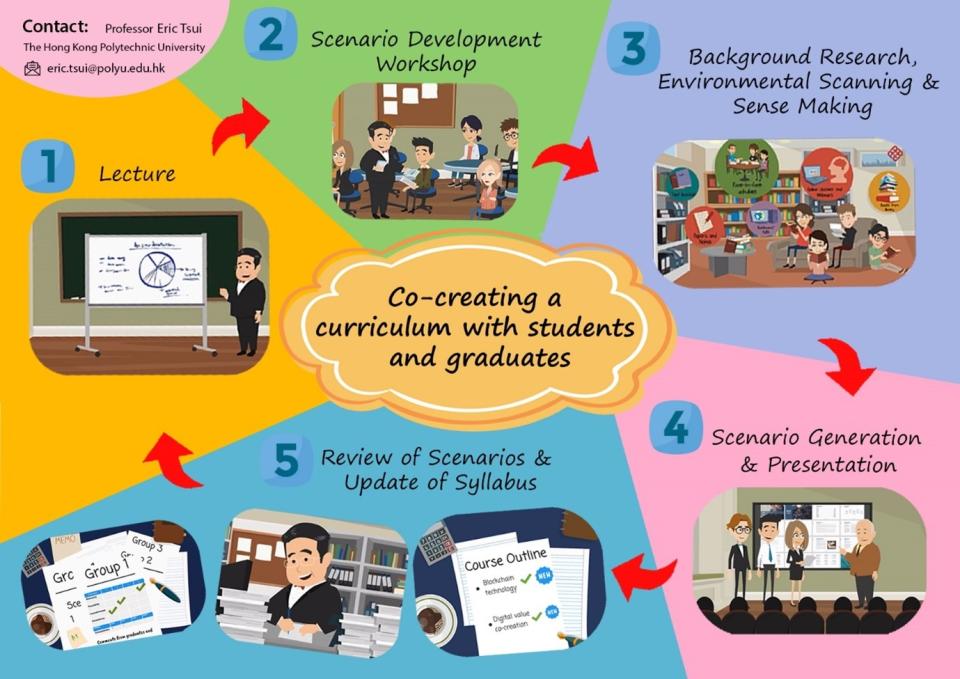

To foster successful co-creation of curricula content among students, we adopt a five-step approach. This gets students developing future scenarios based on how they believe a given discipline or topic will evolve. This process helps students learn valuable skills – such as critical thinking, collaboration, research capabilities and social intelligence – and moves their mindset towards lifelong learning.

Step 1: set the question

A priming question is set, for example: “What will process management systems be like in five years’ time?” It is important that the question set is sufficiently general so that many factors, in principle, may influence the response. However, it is important to note students’ learning lies in the process and not in the accuracy of the scenarios they generate. If you wish to build up a repository of scenarios over several years for trend and impact analyses, set the same or very similar questions for a given subject each year.

Step 2: identify the influences

Working in groups, students identify a list of global trends and driving forces that may influence their response to the question. Students label similar trends and driving forces and group them into categories. Typically after this step, 10 to 12 groups remain, representing the key influencing factors for answering the priming question.

Step 3: build the matrix

A 2x2 matrix, with axes detailing the likelihood of occurrence against the extent of their impact, is drawn up. Students pick two groups of influencing factors that they believe sit in the quadrant corresponding to high uncertainty and high impact. You do not have to select that quadrant, but we believe the scenarios generated from that section of the matrix tend to be the most exciting.

To do this, students carry out more background research as well as identify and assess quality of data to support their reasoning, discussions and decision. Students are not assessed on the outcome of scenarios as it is the learning process they go through that is considered most valuable. So, they are assessed on the thoroughness of the background research, use of quality data and the reasoning they apply to generate the scenarios.

Step 4: forming four scenarios

For the two groups of consolidated trends that students place into the high uncertainty and high impact quadrant, they further identify two “axes of uncertainty” that will influence the outcome of the scenarios. These two axes of uncertainty need to be independent of each other, such as quality and volume, or features and customisation. As each axis is a sliding scale, there are two extremities such as high and low, minimum and maximum, existing and non-existent. With these two independent axes, four scenarios can be derived from the combinations of the extremities.

Step 5: the narratives

Finally, students are asked to write narratives for each of the scenarios. Each story covers the title, description, driving forces or trends, the agents, impacting time and period. All scenarios are uploaded to a repository for further analysis by the teacher.

Once the scenarios are collected, the teacher reviews them all against evidence of industry development to ascertain if any part of the scenarios is becoming reality.

These student-generated scenarios can reveal or remind instructors of relevant topics of growing importance inadequately covered by the current curriculum, ahead of the next module or course. Instructors can then revise or expand the curriculum to cover those emerging topics in their future teaching. Scenarios may take several years to come to fruition, so it helps to build up a scenario repository from consecutive student cohorts.

We have operated this method for three years and there are collaborators trying variants of this method within our institution and others. There are major benefits with this co-creation approach to teaching.

First, during the scenario-development process, students work in groups and learn about global trends and driving forces affecting their discipline. They need to:

-

conduct background research

-

identify and assess the quality of data

-

learn and improve their sensing and interpretive abilities and practise critical-thinking and storytelling techniques.

We bring in graduates to work with students, especially in the step of identifying trends and driving forces, then assessing their likelihood and potential impact. This helps students gain early exposure to real-world constraints and pragmatism ahead of joining the workforce.

We encourage local students to form groups with foreign students, which can aid their understanding of the East-West cultural divide and enhance trans-cultural knowledge.

As this assignment runs over several weeks, it helps students to develop collaborative skills. Groups must agree on the use of common tools to support their communication and co-activities. Over the years, hundreds of scenarios have been accumulated for each of the priming questions. This is a valuable resource for lecturers who can revisit these scenarios regularly and ascertain areas that have not been covered adequately or need to be added to the curriculum. This way, the curriculum is regularly updated in line with changes in wider society.

Eric Tsui is senior educational development officer at the Educational Development Centre, the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.