View the THE Asia University Rankings 2021 results

In the sort of formal ceremony beloved in this part of the world, VIPs posed on stage, holding shovels decorated with giant gold bows, to mark the launch of a University of Hong Kong (HKU) campus redevelopment project.

Covid restrictions meant that the guests wore face masks, and the event, held in January, could be viewed only online. However, the message was clear. Not even a pandemic was going to stop construction on a new home for the business school, sports facilities and residences. Over the next few years, HKU plans several other infrastructure projects and hundreds of new hires at the professorial level.

THE Campus resource: Five key trends for rethinking higher education in Asia post-pandemic

Hong Kong’s flagship institution is not alone in engaging in what seems like a spending spree. Similar developments are happening at universities across the more affluent parts of East and South-east Asia, where new institutes, departments and degree programmes have been cropping up. Much of this recent rise in spending comes from state coffers, as well as from government messaging to the business sector that education should be a target for philanthropy.

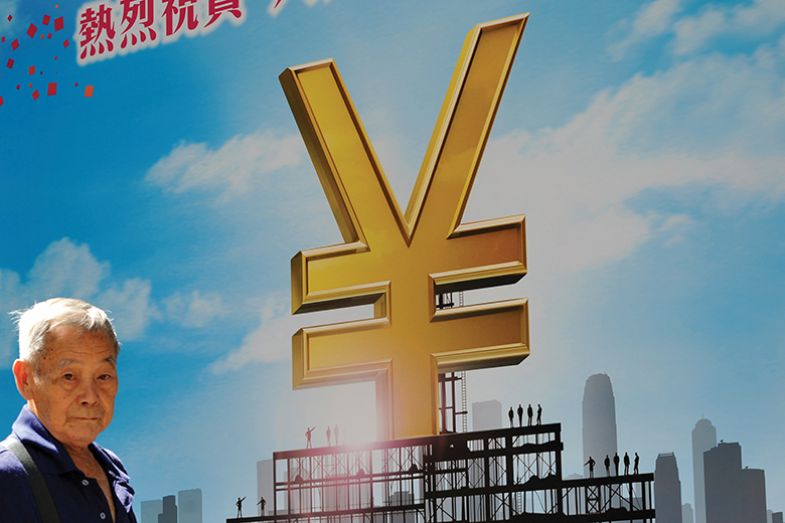

Mainland China’s higher education budget, for example, grew by 12 per cent from 2019 to 2020. Meanwhile, companies with close state ties have responded to the siren call that they are expected to pitch in, especially in fields of study deemed politically or socially important. Vanke, a property conglomerate with links to the government, funded an eponymous public health school at Tsinghua University in spring 2020, right at the height of the country’s Covid outbreak.

Japan may not have the same annual budget increases as mainland China, but it too is making a concerted effort towards new financing. The government announced this year that it aims to raise capital for an eye-popping ¥10 trillion (£70 billion) university research fund by 2022. If it succeeds, it will have a fund worth double the size of Harvard University’s endowment. Institutions would be expected to contribute their own donation efforts after that.

Relatively smaller high-tech states are also trying to muscle in on the competition for top academics and students. Taiwan will spend an additional NT$83.6 billion (£2.2 billion) over five years to develop universities, teaching and innovation, according to a 2019-20 report from the Education Ministry. The “Higher Education Sprout Project” will also include incentives to offer “internationally competitive packages” for foreign academics, while Taiwan’s Defence Ministry will pitch into higher education institutions for the first time with an additional NT$5 billion programme for research.

Growth is happening in developing nations, too. Malaysia, for example, has set aside an impressive 20 per cent of its entire 2021 national budget for education.

There are also signs of development in other parts of Asia, even if they have been harder hit by Covid. India has ambitions to double the size of its higher education sector under its new National Education Policy. Meanwhile, its latest budget, announced in February, included 500 billion rupees (£5 billion) for the first five years of a new National Research Foundation (NRF). While state universities are struggling financially, private institutions have grown rapidly despite the Covid crisis. One case in point is O.P. Jindal Global University, which welcomed 209 new faculty in 2020 and an additional 112 this January. More than half have international qualifications, and many are joining the university’s quickly expanding law school.

Higher education systems in this part of the world are flourishing in part because they were spared much of the financial damage felt by major English-speaking nations that have become reliant on income from international students. Institutions in the US, the UK and Australia, for instance, have seen drastic drops in revenue as Covid-19 kept overseas students away.

Asian institutions were never highly dependent on international fees to begin with, and they have continued to rely on high demand from local or regional students. They are also being bolstered by rising state support and growing local philanthropy, both of which are closely tied to notions of nation-building and social responsibility, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Hugo Horta, an HKU associate professor studying the social contexts and policies of education, says Asian and Western higher education systems were “almost the opposite” in terms of their approach to financing.

“In Western countries, like the US, the government became sidetracked away from funding universities, which are now almost completely reliant on the market. So to fund research, which is expensive, they need international students or donors. That’s not happening so much here,” he says.

The jump in revenue is perhaps most striking in Hong Kong. A Times Higher Education analysis of the 2019-20 financial statements of all eight public universities shows that all recorded a rise in both government funding allocations and income from private donations. Income from tuition fees held steady or even grew slightly.

Social unrest that led to student arrests, police actions on campuses and a new national security law may have stirred up serious concerns about academic freedom in the territory. However, it seems that those factors have, so far, not had any negative effect on institutions’ academic performance or bank balances.

The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) – the two campuses most damaged during the 2019 protests – have edged up in the 2021 THE Asia University Rankings. CUHK’s philanthropic donations nearly doubled, from HK$764 million to HK$1.3 billion (£72 million to £122 million), while PolyU’s jumped from HK$235 million to HK$393 million, according to their financial statements.

William Lo, associate head of the department of international education at the Education University of Hong Kong, says these figures suggest that “the problems have no influence on Hong Kong universities’ funding”. If anything, the increased donations might be used as a carrot for institutions to work more closely with Beijing, he adds, noting that the focus among policymakers is on “how Hong Kong can contribute to China’s national development”.

However, Lo also warns that the more critical aspects that make Hong Kong education unique in the region should be preserved for it to continue as a global force.

Meanwhile, it seems that the stereotype that new Asian money is going only to STEM and medical fields does not hold true. Hong Kong Baptist University’s philanthropic donations more than tripled from HK$81 million to HK$307 million, partly because of its largest-ever gift for a new facility – the Jockey Club Campus of Creativity. Lingnan University, a liberal arts college, recorded an almost eightfold increase in donations, from HK$26 million to HK$204 million.

Bernadette Tsui, associate vice-president (development and alumni affairs) at HKU and author of The City with a Heart, a book about philanthropy, says “giving in this part of the world has grown tremendously in the past two decades”.

In part, she attributes this to the fast pace of educational attainment in broader society. “People believe in investing in education, maybe all the more because older generations did not have the opportunity to attend university, or often not even secondary education,” she says.

HKU’s Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, named after a tycoon who fled China as a refugee and dropped out of high school before making his fortune, is on a hiring spree that aims to greatly increase its capacity by 2027, partly driven by the state setting aside more spaces for a rising number of medical and nursing students.

Vivian Lin, executive associate dean of the faculty, says it aims to replace 100 retiring professors and to add 140 new academic staff in that timeframe. That does not include additional hires at the PhD and postdoctoral levels for research purposes.

She is straightforward about the medical school’s goal to poach talent from overseas. “We were going to do so at international conferences last year, but you could say that plan got ‘Covid-ed’,” she says.

Now, the school has turned to global headhunters, placing adverts in top Western medical journals and keeping an eye on medical directors and department heads overseas.

Singapore, a historical rival to Hong Kong, is also on the hunt for international professors, promising globally competitive salaries.

The National University of Singapore’s Presidential Young Professorship Scheme, launched in 2019, offers five-year grants worth S$250,000 to S$1 million (£137,000 to £548,000).

“We are keenly aware that in these trying times, new PhD graduates and postdoctoral researchers are entering a very tough job market,” says an NUS spokeswoman. “By continuing to hire new talent, NUS is investing in the next generation of scholars who can help address our society’s crucial needs.”

When Japan announced its new strikingly large “university fund” in January, experts interpreted the move as a way to jump-start a new era of higher education fundraising in the country.

Akiyoshi Yonezawa, vice-director of international strategy at Tohoku University, believes the fund is only a first step towards Japan getting its universities back on better financial footing.

“The Japanese government expects top national universities to become more financially autonomous,” he says. “The leaders of top national universities also, in general, welcome this because they can get their own financial base, which enables more stable and autonomous management.”

Public support for higher education also plays a role in government funding and decision-making.

“According to five years of research findings, it is widely believed that Japanese HE is considered to be a ‘public good’ and should be funded by government,” says Futao Huang, a professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, whose working paper on the topic, based on interviews with policymakers, presidents of national professional associations, institutional leaders and senior university leaders, was published earlier this year by the Centre for Global Higher Education.

The decision-makers interviewed by Huang’s team said research represented a “greater contribution to the public good than teaching” and that doctoral education contributed more than undergraduate teaching.

“Specifically, [the interviewees] argued that Japan’s national universities play a decisive role in contributing to the public good by promoting social justice, equal access, innovative basic research, and advancing the development of science and technology at the regional, national, and international levels,” the paper says.

However, for all the money being thrown at higher education, Asian states have still not overcome vast cultural and linguistic barriers to become as international as some of the world’s top institutions, according to HKU’s Horta, who has also studied or worked in his native Portugal, the UK, the US and Japan.

“East Asian universities are increasingly collaborating on a global scale, but outside of Hong Kong, they really struggle to attract foreign faculty. And to attract international students, you need international staff,” he says.

“It’s not just [about] money. You need to fully integrate international staff. You need to change curricula. And you need academic freedom.”

For now, Horta predicts, “the very best Asian students who can afford it will still go to Europe, North America and Australia”, if only to have a truly global experience.

“If I were a top mainland Chinese student who had offers at both Tsinghua and Caltech – and I had the resources – I’d go to Caltech. I can learn English, adapt to a new culture and earn some clout when I come home,” he says.

He also notes that the financial situation in cities such as Hong Kong and Tokyo does not reflect the reality of the broader region, where many institutions in South and South-east Asia remain “very underfunded”. That said, he believes now would be the time to change that situation.

“The perfect time to put money into something new is during a crisis,” he concludes.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login