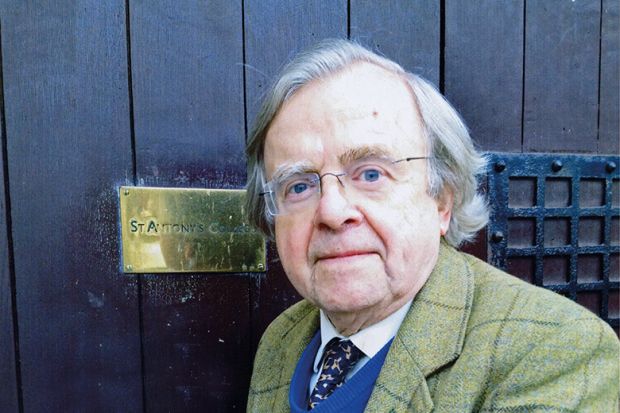

Richard Clogg is emeritus fellow of St Antony’s College, Oxford. He taught at the University of Edinburgh and the University of London, most recently as professor of modern Balkan history, and wrote a number of standard works such as A Short History of Modern Greece (1979) and A Concise History of Greece (1992). His latest book, Greek to Me: A Memoir of Academic Life (I. B. Tauris), was published earlier this year.

Where and when were you born?

In Rochdale in November 1939. Not long afterwards, households throughout the country received a flyer instructing civilians on how to conduct themselves if the Germans invaded. I still have the flyer. My mother, with a new-born baby, must have been terrified.

What was your most memorable moment at university?

In 1961, I attended a seminar organised by the Middle East Society at the University of Edinburgh on the rock-cut churches of Cappadocia. All those present were either faculty or postgraduates except myself and an American undergraduate, Mary Jo Augustine, then studying at the University of Oregon but spending a year in Edinburgh. Inevitably we talked, and I was smitten. A year later we were married in Oregon. Besides acquiring a marriage licence, we needed certification by the State Board of Eugenics that we were fit to breed.

What spurred you to embark on the serious study of modern Greece?

[It] was prompted by the summer vacation of 1960 spent in helping to uncover wall paintings in the 13th-century church of Hagia Sophia in Trebizond [Trabzon]. These had been covered with plaster when the church had been converted to a mosque [during the Ottoman period]. In 1960, the church continued to serve as a mosque, but subsequently became a museum. In 2013, however, it reverted to being a mosque. A device has now been installed which, apparently, magically renders the wall paintings invisible at the times of Muslim worship. During my time in Trebizond I became interested in the large Christian presence in the city before the expulsion of the Greeks and Armenians in the early 1920s, less than 40 years before my first visit to the city.

What have been the most gratifying responses to your two major overviews of modern Greek history?

[The fact that they] have been adopted as textbooks in Greek universities, although they were not written with Greek university students in mind, but rather non-Greek readers for whom no knowledge of Greek history could be taken for granted. If I had any reader particularly in mind it would be a second-, third- or fourth-generation member of the Greek diaspora who wished to learn something of the country from which their parents, grandparents or great-grandparents had emigrated.

What was the nature of the controversy about the historian Arnold Toynbee that you wrote about when you were also based at King’s College London?

I had heard vague rumours of the great controversy which had arisen when the young Arnold Toynbee, then aged 30, had been appointed the first Koraes professor [of modern Greek and Byzantine history] and decided to learn more about why his tenure of the chair was so short-lived. The controversy arose from Toynbee’s exposure in the Manchester Guardian of atrocities committed by Greek forces in Asia Minor during the Greek-Turkish war of 1919-22. The Anglo-Greek donors who had put up the money were bitterly disappointed by Toynbee’s growing sympathy with the Turkish nationalists. The controversy led to what Toynbee himself called his "involuntary resignation" from King’s [in 1924]. He went on to become perhaps the most famous historian in the world in the 1950s and 1960s. I found a treasure trove of material in the college archives [and] was able to reconstruct the controversy more or less on a day-by-day basis.

How would you describe the response of the institution?

My book Politics and the Academy: Arnold Toynbee and the Koraes Chair was published in 1986, at a time when the college’s financial position was dire and 200 members of staff faced redundancy. The powers that be were not amused by the book as they were intending to go cap in hand to benefactors, including rich Greeks who retained a kind of proprietorial attitude to the Koraes chair.

Do you believe that universities should be less secretive about their pasts?

In my experience, universities are unusually secretive in regard to the not inconsiderable number of scandals in their past or present. When I was writing my account of the Toynbee controversy, I needed to consult the records for the early 1920s of the board of studies in history, of which I was at the time a member. These minutes dealt with revisions of the syllabus, the appointment of examiners, the scheduling of examinations and other mundane matters. But I was told that these records were closed for 100 years, as long as those of the Special Branch or of the Royal family.

Should universities seek funds from philanthropic donors, particularly in area studies?

Recently, King’s has received generous donations from the [Stavros] Niarchos and [A. G.] Leventis foundations to re-endow the Koraes chair. I find something rather distasteful in approaching Greek foundations for funds, given the current plight of Greek universities, not to mention Greek academics, although the Niarchos and Leventis foundations do not have a reputation for interfering with the beneficiaries of such donations.

Tell us about someone you’ve always admired

C. M. (“Monty”) Woodhouse. A brilliant scholar, and who, but for the Second World War, would almost certainly have become an academic. During the war he commanded the Allied mission to the Greek resistance. After the war, among other positions, he was director of Chatham House, and subsequently became MP for Oxford. He was one of the relatively few Conservative MPs who was outspoken in his opposition to the colonels’ dictatorship [in Greece, 1967-74] and was always ready to come to the aid of opponents of the regime, including those with whom he had encountered serious problems in the mountains of Greece during the occupation.

What advice did you give your students?

Towards the end of my career I was supervising only postgraduates. My advice to them was to be circumspect in dedicating their theses to current boy- or girlfriends, or even spouses. I would point out that it was only safe to dedicate the thesis to your mother as, at that time, you could have only one of these.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login