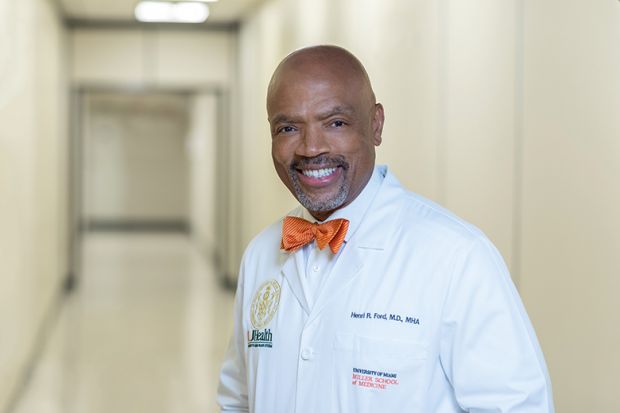

Henri Ford is dean of the Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami. The Haitian paediatric surgeon is also president of the 90,000-member American College of Surgeons, chair of the Council of Deans of the Association of American Medical Colleges, and a podcast host.

Where were you born?

I was born in Port-au-Prince, the sixth of nine children of a dynamic preacher, Guillaume Ford, and a prayer warrior named Jeanne Jean-Louis. At an early age, they taught us the importance of faith in God, the value of education and service to others.

I understand that you have great admiration for them, especially given their decision to leave Haiti after your father’s outspokenness against the Duvalier government.

My dad was a proud individual. It’s a story I don’t share often, but he recognised at some point – as he was becoming a young adult, around 21 – that his father had signed his birth certificate as a witness. And he went and confronted him, asking what’s going on. Basically, his father, my grandfather, had another family. As a result, my father changed his last name and took his mother’s name. It embodies a lot of what he ended up inculcating in us as children, about being a principled individual – he was always about excellence.

How were things different in the US?

Coming from Port-au-Prince and ending up in Brooklyn, not really speaking English and trying to assimilate, was a little bit traumatic initially, being somewhat ostracised and bullied in high school. I remember as a ninth grader – I had just gotten to the States that September – that every person had to read a paragraph of a book. And every time they got to me, the whole class started cracking up, because they knew I was about to butcher the English language. And one of my teachers, Mr Stewart, he always told me, “Just ignore them, and just keep trying.” I’d never trade these experiences for anything; they helped mould me into the person that I became. The resilience and endurance that I acquired from those early years convinced me that I can do just about anything if I stick with it.

Some people might say that’s proof that we don’t need affirmative action.

Let’s be clear: I benefited from affirmative action, without question. At Miami, that’s reflected in our medical school stressing “inclusive excellence” in its applicant evaluations. There are many individuals who are very talented, who have demonstrated their ability to overcome, and these individuals just need to be able to have a chance.

What else do you do to boost your school’s attractiveness?

An important element is community service. About two-thirds of our students participate in events such as monthly health fairs in under-served communities, where the students provide free care under faculty supervision. And while they may not all stick with it, more than half of our under-represented minority students will tell you that they aim to serve under-served communities when they finish.

What one event most changed you?

In 2015, I led a team that performed the first successful separation of conjoined twins in Haiti. It was a gruelling seven-hour procedure, the culmination of nine months of meticulous preparation. It was gratifying to work in my native country alongside Haitian health professionals.

Is artificial intelligence likely to make a major impact in healthcare and medical training?

AI is going to revolutionise our approach to medical education, healthcare and so much more. It’s a powerful tool, and it has to be incorporated into just about everything we can do. It can help students master the voluminous amount of information that’s being thrown at them, it can help them diagnose problems, come up with treatments and, hopefully, advance novel cures.

What are you seeing already?

At Miami, we’d used the century-old Flexner approach to medical education – two years of basic science instruction and two years of clinical work. And we introduced what we felt was a radical departure from Flexner, getting our students into the clinical part pretty much immediately. As chair of the AAMC’s Council of Deans, I brought a Microsoft expert to our recent conference, who challenged us to get those students immediately familiar with using AI tools. We already see that applying generative AI in the patient setting is allowing the physician to not turn their back on the patient as they’re trying to input data, but to maintain face-to-face contact, improving the feeling of personal attention. We’re all excited about it – we just have to make sure we have the guardrails, because every single iteration is smarter and more powerful.

Are academic medicine and its funders putting too much emphasis on inventing new drugs and devices, as compared with prevention?

This is evolving, as people recognise that if I take a patient with asthma, or a patient with diabetes and hypertension, who lives in a food desert, and I fix that person’s problem, that person may go back [home] and buy a sugary drink because there is no fresh fruit being sold [in the area] or they can’t afford it. And that person is going to be back in your emergency room.

But can a doctor fix a food desert or the polluting highway running past the patient’s house?

Rudolf Virchow was a German pathologist and social activist who said that the physician has to be the attorney for the poor, and that part of our social responsibility is to address this.

What would that look like – the creation of activist physicians?

As president of the American College of Surgeons, my responsibility is to meet with legislators and make them understand how we can make sure that surgeons are equipped with the tools necessary to heal all of our patients with skill and trust. Health policy has to play a critical role in this whole thing.

What keeps you awake at night?

Inequities in the medical profession, patient care and community health – which we are working hard to remedy.

paul.basken@timeshighereducation.com

CV

1976-80 BA in public and international affairs, Princeton University

1980-84 MD, Harvard University

1984-91 surgical internship and residency, Cornell Medical College

1987-2005 fellowship and professorships, University of Pittsburgh

2005-18 professor of surgery, University of Southern California

2006-09 master’s degree in health administration, USC

2018-present dean, Miller SChool of Medicine, University of Miami

2022-present chair, Council of Deans, the Association of American Medical Colleges

2023-present president, American College of Surgeons

Appointments

Phil Taylor will be the next vice-chancellor of the University of Bath, replacing Ian White, who is stepping down in July. An electrical engineer, Professor Taylor joins from the University of Bristol, where he has been pro vice-chancellor for research and enterprise, having previously served as head of the School of Engineering at Newcastle University. Pamela Chesters, Bath’s chair of council, said Professor Taylor’s “exceptional academic record and strong experience in industry and commerce” would help the university “build on its positive trajectory and achievements to date”.

Peter Todd has been appointed dean of Imperial College Business School, moving from his current post as director general of HEC Paris in September. He succeeds Franklin Allen, who has served as interim dean at the business school since September. Professor Todd was previously dean of the Desautels Faculty of Management at McGill University. He said he was “thrilled” to be joining an “exceptional global institution with an unsurpassed reputation for research excellence and a unique entrepreneurial spirit”.

Ian Bruce is joining Queen’s University Belfast as pro vice-chancellor for the Faculty of Medicine, Health and Life Sciences. He is currently vice-dean for health and care partnerships at the University of Manchester.

Louise Dixon is joining Glasgow Caledonian University as pro vice-chancellor for education. She was previously dean of the Faculty of Science at Victoria University of Wellington. Glasgow Caledonian has also appointed Caroline Bysh pro vice-chancellor for engagement, and Joanna Lumsden dean of the School of Computing, Engineering and Built Environment.

Barbara Casu will be the next deputy dean for faculty and research at Bayes Business School, part of City, University of London. She has been head of the Faculty of Finance since 2021.

Erik Hurst has been promoted to become director of the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago, having served as deputy director since 2017.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login