Textbooks have long been the Cinderellas of academic publishing, getting the teaching chores done while the research papers and monographs take all the glory. For students, however, textbooks are the foundation of their subject knowledge – and they are well aware of the effective obligation to buy the recommended texts.

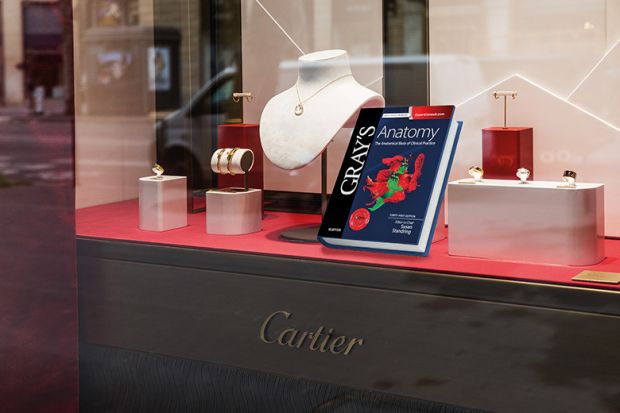

The trouble is that those texts come at a considerable price. Perhaps the most famous textbook in the world, Gray’s Anatomy (first published in 1858), costs about £175 for the full version. In economics, John Sloman’s equally vital Economics – into its 11th edition since 1994 – is nearly £60.

These are sums – substantial even for the wealthiest – that few students factor into their budgets, not least because reading lists may be known only once their course has begun. Poorer students may limit their purchase of core texts – but relying on cheaper alternatives comes at a cost to their learning, as well as to social mobility more widely.

Plenty of entirely free alternatives are available, too, of course. Wikipedia is just one, long banned from bibliographies but still, no doubt, widely used. Anti-plagiarism software has kept direct cutting and pasting from it under some control, but that has engendered a false sense of security, allowing AI to creep up on us almost unawares. Services such as ChatGPT – emerging just as cost-of-living pressures escalate – could herald the online tsunami that finally sweeps away academia’s time-honoured texts.

As academics, we can rail against this prospect. We can assert that it is precisely because of the free availability of unreliable sources that, more than ever, students need access to core textbooks. But we are complicit in a system that obliges them to spend exorbitant, even extortionate, sums to fully participate in the learning they have already paid for via their tuition fees.

If popular budget reference books are a guide, then core textbooks should cost about £15 – and much less for the e-book version. But how to get there from here? Publishers will no doubt argue that the high prices of core textbooks are necessary to subsidise those that do not find broader acceptance. They are unlikely to agree to significant price reductions.

So it will probably be down to academics to cut the publishers out of the picture. But that isn’t easy. My own experience of doing so may serve to highlight the opportunities – and the opportunity costs.

Having long been troubled by the pricing of my own international business textbook and the understandably low purchase rate, I was glad to be able to reclaim its copyright recently. My plan was to republish it with a certain well-known online retailer so that students could buy it for the price of a coffee and a muffin.

But there were a few surprises along the way. Naively, I had expected the process to be slick, professional and involve minimal cost. It was anything but. I was forced to outsource design and layout costs at an upfront cost of several thousand pounds – which I may or may not recoup in royalties.

In addition, I had been assured that the book would be published under the company’s brand, avoiding the impression of self-publication – which comes with a particularly large stigma in academia given peer review’s common perception as a badge of quality. Instead, I was staggered to find this retail giant turning to an independent company to release the paperback version. Since this means the textbook is considered self-published anyway, I might have simply approached that organisation myself and perhaps saved some money.

On the positive side, I did manage to bring the e-book version in at less than £10 and keep the paperback to below £20. I now feel that I can recommend my own textbook to students without apologising for the price. Nevertheless, I have the lurking suspicion that I have escaped one corporate behemoth only to fall into the clutches of another. Surely there is another way.

I propose creating a cooperative venture, in which authors have a stake in the publication process. Without the financial demands of a parent corporation, administrative costs should be lower, allowing prices to be set at affordable rates. There would be some upfront costs, but for an e-book these should be modest.

Universities may be willing to offer seed funding in return for a share of the royalties – particularly given the positive impact the scheme would surely have on student success and satisfaction scores. Of course, some universities also have their own commercial presses, but since the cooperatives I envisage would be unlikely to significantly challenge their revenues, I suspect the dinosaurs and mammals could coexist.

Quality assurance would have to be addressed, but peer review could be conducted among the members of the cooperative, liberating further efficiencies. Any biases would need to be controlled for, but in any case, there are few guarantees of validity better than having the students question the author directly in class – with revealed faults corrected in subsequent editions.

At these lower prices, core texts could retain their pre-eminence – indeed, enjoy far greater take-up – thereby protecting educational standards. Furthermore, student budgets could stretch to alternative textbooks as well, dramatically improving access to full reading lists and relegating AI into the supporting role where it is most effective.

Far from the end being nigh for textbooks, it is time for them to reclaim the centre ground in teaching and learning.

Michael Wynn-Williams is senior lecturer in international business at the University of Greenwich.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login