In 2017, the University Grants Commission (UGC) – India’s main regulatory body for higher education – announced a new initiative to select 20 “Institutions of Eminence” (IoEs). The objective was to identify the 10 best public and 10 best private universities and grant them complete autonomy from the UGC and other regulators. The 10 public institutions would also receive up to 10 billion rupees (approximately £100 million) each.

The thinking was that the additional funding and autonomy would allow these IoEs to prosper and compete more effectively in world university rankings. But the scheme struggled from the start. Initial shortlisting had to be rerun amid concerns that the wrong indicators had been used, and the first report of the Empowered Expert Committee (EEC), published in May 2018, recommended only three public and three private universities for IoE designation.

The EEC’s second report, published later the same year, recommended a fairly long list of public and private universities, and the UGC then whittled that down to 10 public and 10 private universities, including two yet-to-be-established private institutions.

Four years on, though, the initiative seems to have fizzled out. To date, there are only eight public and four private IoEs, and, with the exception of Shiv Nadar University’s addition in October 2022, this list has been frozen since 2020. In March 2023, a parliamentary panel recommended that the process for granting IoE status be accelerated, but nothing seems to have happened.

The reasons are not clear. Ministers might have simply lost interest – although that would be quite remarkable for a government that widely proclaims its intent of recovering India’s past glory as a knowledge power.

The other universities have also struggled to meet the stipulated criteria. When, in September 2019, the Ministry of Human Resource Development – whose remit includes education – approved the selection of the IoEs, it asked several of them to furnish more detailed information or fulfil additional requirements.

For example, five private institutions were asked to submit reports illustrating “their readiness for commencing academic operations as IoEs”. The reports issued by three of them – the Kalinga Institute of Industrial Technology, the Vellore Institute of Technology and Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham – were approved by mid-2020, but their IoE status has not been confirmed. And in September of that year, the EEC recommended the removal of Jamia Hamdard from the list owing to its involvement in a legal dispute.

The Bharti Foundation, which was to have established the new-build Bharti Institute, pulled out due to an inability to acquire land, and the other “greenfield” institution, the Jio Institute, is reportedly struggling to begin academic operations.

The ministry also asked two state universities – Jadavpur University in West Bengal and Anna University in Tamil Nadu – to obtain 50 per cent of the promised 10 billion rupees from their respective state governments. Both governments refused, however, and the two universities are no longer expected to be designated as IoEs.

The EEC completed its term in February 2021 and has not been reconstituted. The National Education Policy of 2020 proposed to replace the UGC with a new Higher Education Commission of India (HECI), whose responsibilities are expected to include completing the selection process of the IoEs, but the body has not yet been created. Even when it is established, whether it fulfils that part of its mission is open to some doubt.

In the meantime, despite the promises to the contrary, the existing 12 IoEs continue to be choked by multiple government regulators. Even the government’s pledged funding has fallen short. As of May 2023, only two of the eight public IoEs had reportedly received more than 50 per cent of the 10 billion rupees due to them. The University of Delhi had received less than 10 per cent.

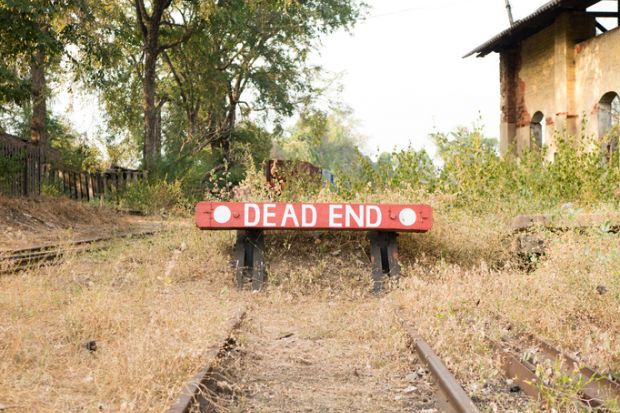

In sum, the current situation is rather dismal. What started as an earnest attempt to promote excellence in higher education appears to have run its course without any significant achievements to its credit. For most IoEs, the only benefit is the reputational one of having the IoE tag itself.

The author prefers to remain anonymous.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login