In the heart of Europe lies a country that seems to prove many common assumptions about higher education wrong.

In its higher education system, observers believe, Switzerland has managed to knit together the vocational prowess of Germany, the egalitarian entrance system of France and the highly ranked research universities of the Anglo-American world.

The country is one of the world’s richest (not to mention happiest), ranking alongside petro-states and international tax havens in terms of average purchasing power.

But despite the claims of economists that the “knowledge economy” requires workers with the abstract reasoning and critical thinking instilled by an academic higher education, Switzerland has stubbornly refused to follow other developed countries such as Australia, the US and South Korea in sending anywhere near the majority of its young people into academic higher education.

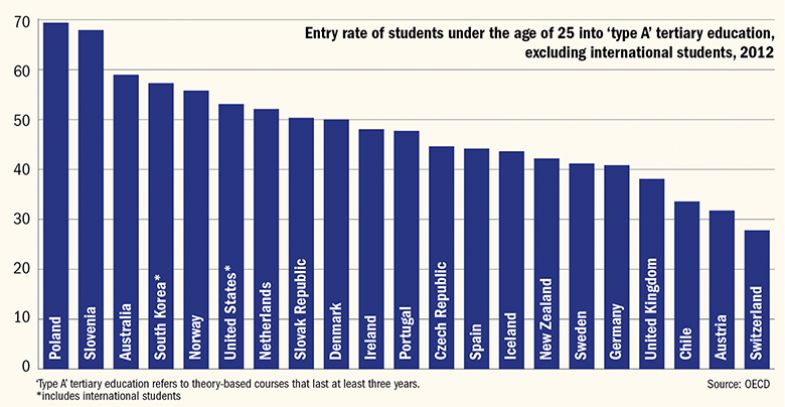

According to the most up-to-date figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, just under 28 per cent of Swiss aged under 25 enter what is called “type A” tertiary education – theory-based courses that last at least three years – the lowest proportion among the countries for which the OECD has figures. In 2014, the organisation chided Switzerland for its performance.

But Swiss university leaders seem unperturbed. “There are only so many people who need a classical university education for the job they will do,” said Michael Hengartner, president of the University of Zurich.

If anything, the concern in Switzerland now is that too many people are going to academic universities. “A lot of voices say we should keep [university enrolment] at this level because vocational education training is the reason why Switzerland is doing so well at the moment,” said Matthias Ammann, a fellow of Avenir Suisse, a free-market thinktank.

Although Dr Ammann’s thinktank has recently lobbied for tweaks to the system, overall he is content with it. Just 8 per cent of Swiss youngsters are unemployed, well below the OECD average of about 12 per cent. “The numbers speak for themselves,” he said.

At age 16, only a small fraction of youngsters – as low as 15 per cent in the more rural eastern cantons – continue with their education full time, on an academic track that leads to their taking the matura qualification, which allows entry to an academic university, Dr Ammann explained.

Most young people start down a vocational path, working part time in a company but still attending school, normally for two or three years, he added.

Indeed, the “Swiss paradox” of riches despite its relative paucity of graduates is so striking that it has been used by the University of Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang to challenge the very idea of the “knowledge economy”. The country helps to demonstrate that higher education functions largely as a sorting system for employers, rather than actually making workers more productive, he has argued.

In other countries, many universities offer specific training as well as cultivating higher mental skills. But in Switzerland, which boasts nine universities of applied sciences alongside 12 traditional universities, the distinction between the two missions is strictly policed.

Unlike the UK’s former polytechnics, which attempt to “play in the same league” as other universities, Swiss universities of applied sciences “are by law encouraged, if not forced, to focus on applied research. They don’t get rewards for publishing in top international journals,” said Marius Brülhart, a vice-dean of the University of Lausanne’s Faculty of Business and Economics. Yet some academics do push back at these constraints, he added.

And to pursue a bachelor’s degree at a university of applied sciences, applicants must have done an apprenticeship first. “The practical experience comes before the BA,” explained Professor Hengartner, the reverse of the situation in most countries.

A growing number of apprentices do now go on to a university of applied sciences, he said. Indeed, the whole ethos of the Swiss system is to allow vocational learners to take multiple paths to universities of applied sciences, or even to academic universities; a trainee electrician “can end up being a professor of electrical engineering”, Professor Hengartner added.

Of course, academics consider university education to be much more than just a cog in an economic machine. Is the Swiss system a little utilitarian?

“Swiss are quite well known for being pragmatic,” Professor Hengartner acknowledged. “But having a small fraction of people going to university, we [universities] have less of a pressure to think ‘employability, employability, employability’ ” than institutions in countries where university study is seen as the key route into the job market, he pointed out.

Peaks and valleys: Swiss at the bottom of academic track

Another oddity of the Swiss system is the lack of any kind of university entrance selection system, except in medicine. The high school matura is “your free ticket of entry into any university”, explained Christian Leumann, rector of the University of Bern.

In this sense, Switzerland is similar to the egalitarian French university system – although there, elite grandes écoles do have tough entrance requirements. The Macron government is currently battling student protesters over its plans to make the system more selective.

Swiss high school graduates’ right to take almost any course at any university makes ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich a particular anomaly in the world of “elite” universities: its peers in the upper echelons of world university rankings – the likes of the University of Oxford, Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – have vanishingly small acceptance rates. But ETH manages to boast egalitarian access, low tuition fees (SFr580, about £420, a semester for Swiss and non-Swiss alike) and a stellar research reputation.

Selection occurs in other ways, however, for example during the school system. Then, as in France, many first-year undergraduates drop out – about a quarter, according to Dr Ammann. In Professor Brülhart’s faculty, the figure is as high as 40 to 50 per cent; they tend to succeed at other universities, but “it’s not pleasant for people who try and fail and lose a year”.

Without a selection process, universities only get three to four months’ warning about how many students they will have to teach, Dr Ammann said. For large, established courses, fluctuations are small and predictable. But for trendy modules – film studies became very popular a few years ago, for instance – a course can become “overrun” with students, said Professor Hengartner, necessitating a rapid boost in the number of teaching assistants and in professorial teaching time.

Could other countries copy the Swiss system? If they want to, they will have to pay up. Switzerland spends close to $28,000 (£19,740) a year per tertiary student (although this does include research), about 70 per cent more than the OECD average.

Companies would need to be willing to take on apprentices. They do so in Switzerland not out of economic self-interest but because they respect national culture and tradition, argued Dr Ammann (although others who spoke to Times Higher Education disagreed – apprentices are a good source of cheap labour and new recruits, they pointed out).

And finally, the Swiss system arguably works only in a country where university attendance has not become an essential middle-class rite of passage.

In the UK, there is a pervasive sense that not going to university compromises a young person’s life chances, said Professor Brülhart. But in Switzerland, “factually and culturally, it’s not true”. Many who take the vocational track have better career prospects than academic university graduates, he explained. The chief executive of Swiss bank UBS, Sergio Ermotti, began his career with an apprenticeship at a local bank, for example. There are “lots of stories where people manage to climb their way up” despite not going to university, Professor Brülhart said.

But this parity of esteem is under strain from foreign values. “We are seeing that foreigners who are not used to this [vocational system] are trying to send their kids to high school” in order to ensure that they get into universities, said Dr Ammann. In more internationalised cities such as Zurich, high school entrance is now highly competitive, he added.

The “Swiss paradox” may yet melt like Alpine snow in springtime.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: No more graduates needed: Switzerland takes its own route

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login