The potential for conflicts of interest to undermine scientific integrity may be moot, but one thing is clear: they are manna from heaven for newspaper journalists with designs on the front page.

Earlier this month, The Times newspaper’s front page story revealed that Coca-Cola has “poured millions of pounds into British scientific research and healthy-eating initiatives to counter claims that its drinks help to cause obesity”. Noting that the UK government had recently rejected calls for a sugar tax despite support for it from Dame Sally Davies, the chief medical officer, the article flagged up a 2013 paper in the journal Plos Medicine, “Financial conflicts of interest and reporting bias regarding the association between sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review of systematic reviews”, which finds that studies funded by drinks companies and the sugar industry are five times more likely than other studies to find no link between sugary drinks and weight gain.

One of the “more than a dozen” British scientists with whom it alleged Coca-Cola had “financial links” was Ron Maughan, emeritus professor of sport and exercise nutrition at Loughborough University. Maughan made headlines earlier this year with a paper suggesting that not drinking enough fluids before driving could be as dangerous as drink-driving. The study was funded, according to The Times, by a non-profit body bankrolled by Coca-Cola, and the firm quickly followed up with a campaign with Shell to sell more drinks at service stations “following the findings of the Loughborough study”.

Simon Capewell, a board member of the Faculty of Public Health, the body that sets standards for specialists in public health, accused the firm of trying to manipulate public and political opinion. “Its tactics echo those used by the tobacco and alcohol industries, which have also tried to influence the scientific process by funding apparently independent groups. It’s a conflict of interest that flies in the face of good practice,” he said.

The story follows similar accusations about Coca-Cola’s activities in the US, published in August by The New York Times. The claim was that the firm funded a non-profit organisation, whose founders included prominent academics, that promoted the message – rejected by mainstream scientific opinion – that “weight conscious Americans are overly fixated on how much they eat and drink while not paying enough attention to exercise”. In the wake of that story, according to The Times, Coca-Cola admitted that it had invested more than $120 million (£78 million) in US research and health partnerships, involving more than 100 researchers.

Then, in late September, The New York Times published another front-page exposé revealing that academic scientists were being enlisted in a “food war” between firms developing and selling genetically modified crops and their opponents in the organic food industry.

Although the newspaper found “no evidence” that the academics’ work was “compromised”, examination of private emails between researchers and the companies revealed that both sides of the debate had “aggressively recruited” academics to campaign and lobby on their behalf. The biotech industry had even “published dozens of articles, under the names of prominent academics, that in some cases were drafted by industry consultants”.

In all cases, the academics and universities involved denied that the firms had any control over their work or conclusions, and the companies themselves denied any sinister motives.

Still, the fact that the stories made it to the front page of highly respected newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic tells its own story about the potential for perceived conflicts of interest to undermine public trust in scientific integrity.

Another example was thrown up by the collapse this summer of Kids Company, a London-based children’s charity popular with politicians and celebrities, amid accusations of financial mismanagement. In interviews, the charity’s chief executive, Camila Batmanghelidjh, cited a 2013 report from researchers at the London School of Economics as evidence that the organisation was well managed. However, neither she nor the report itself pointed out that the study had been funded by a £40,000 grant from Kids Company.

The report’s analysis was glowing. It praised Batmanghelidjh as a “mother figure and role model”, and as an “exceptional” and “highly-capable” leader. “I met [her] in 2007 and was immediately struck by the beauty and profound truth of her simple message: children recover with unconditional and unrelenting love,” wrote Sandra Jovchelovitch, the report’s principal investigator and professor of social psychology at the LSE.

An LSE spokesman said at the time that the report was “not an audit of Kids Company finances or management practices”, but “analysed the model of intervention and care by the charity”. And Jovchelovitch says that the sponsorship did not alter her judgement about Kids Company, which was “the outcome of qualitative and quantitative data analysis, based on the evidence collected”.

“Most research conducted in universities today is sponsored by research councils, government, industry and charities, among other external agents, so there is nothing out of the ordinary in the way we collaborated with Kids Company,” she says.

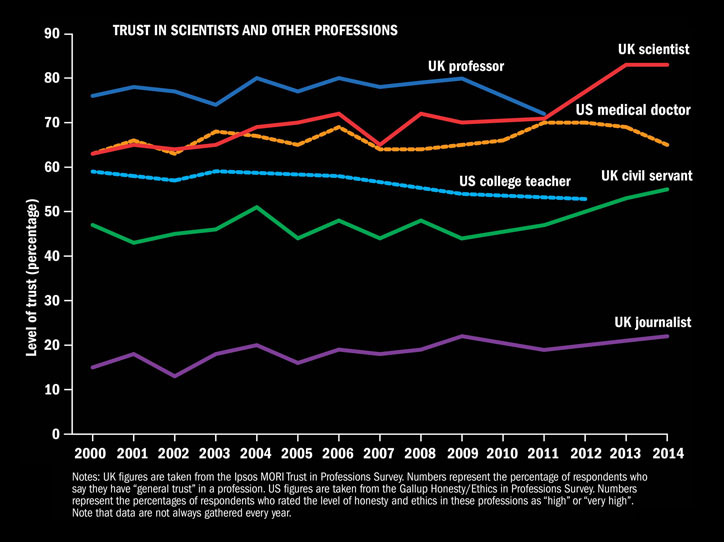

Critics say that this is exactly the problem. In economics, medicine, energy and a host of other subjects, there are fears that financial conflicts of interest give the impression that academic findings are up for sale. And although, according to the most recent figures, public trust in academics and scientists continues to far surpass that in many other professions (see below), there are concerns that at a time when scientific credibility is also under scrutiny over research misconduct and the irreproducibility of many findings, further revelations about conflicts of interest could lead to a collapse in public trust if the issue is not confronted.

Not all financial conflicts of interest are the same. Academics can receive money in the form of consultancy fees, gifts, honoraria or equity in companies. Alternatively, as in the cases mentioned above, companies themselves can directly fund research.

There are no hard data on trends in the first kind of arrangement, but the second can be examined. According to figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, the proportion of total research income from grants and contracts awarded to UK higher education institutions that comes from industry has actually fallen in recent years, from nearly 11 per cent in 1994-95 to just over 6 per cent by 2013-14 – although the actual amount spent by industry doubled over the period, to £313 million. However, in the US, the proportion of university research funded by private industry tripled between 1970 and 2000, according to an exhaustive report on such links released last year, Recommended Principles to Guide Academy-Industry Relationships, by the American Association of University Professors. Still, as in the UK, only 6 per cent of US research is industry-funded.

But while industry funding may be dwarfed by public sources, it can still potentially do a lot of damage to the sector’s reputation if it is seen to introduce biases. Both types of conflict of interest were explored in the 2010 film Inside Job. The film skewered prominent US economists for taking millions of dollars from banks in speaking and consultancy fees while failing to raise the alarm over the growth of toxic financial products that would ultimately wreck the global economy in 2008. It featured an excruciating interview with Frederic Mishkin, a banking professor at Columbia University, who, in 2006, co‑authored a report praising Iceland’s “strong” banking regulation system. Two years later, following five years of wild growth, Iceland’s three main banks had gone bust.

Trust me, I’m a scientist: public ratings of ethics according to profession

“Yeah. And that was the mistake. That it turns out that…the prudential regulation and supervision was not strong in Iceland,” Mishkin says in the film. He goes on to explain that his research partly consisted of having “faith” in what the Central Bank of Iceland had told him. The film then revealed that Mishkin had been paid $124,000 (£82,000) by the Icelandic Chamber of Commerce to write the paper.

Many economists were certainly embarrassed by the financial crisis, but whether the profession has changed its behaviour is less clear. A 2012 analysis by economists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst of the outside interests of 19 of the most prominent academic economists in the US reveals that between 2005 and 2009, 15 members of this group worked for private financial institutions. Three had co-founded their own firms. One economist worked for three different banks.

“The overwhelming evidence is that the economists rarely, if ever, disclosed these financial affiliations in their academic or media papers during 2005-09,” states the paper, “Dangerous interconnectedness: economists’ conflicts of interest, ideology and financial crisis”.

The study then looks at the same economists in 2011. By then, they were formulating policy on how to prevent another crisis. But 14 still had links to financial firms. Disclosure had improved, but was still low: on average, the academics now revealed their conflicts of interest in 28 per cent of their academic papers, and 44 per cent of media articles – although “peer pressure has begun to establish a norm” for disclosure, the paper argues.

The following year, the American Economic Association set new disclosure rules for its own journals. Every paper now has to declare its source of funding, and authors must reveal any “significant” income – defined as more than $10,000 in a three-year period – from “interested” parties with a “financial, ideological, or political stake” in the research.

Gerald Epstein, professor of economics at UMass Amherst and one of the authors of “Dangerous interconnectedness”, believes that the new rules are having an impact. “There is clearly much more disclosure of possible conflicts both in the AEA journals…and in other journals and websites. Journalists are also asking more about this when they interview people,” he says.

But Cary Nelson, emeritus professor of English at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and an outspoken voice on academic conflicts of interest, believes that the AEA rules are “quite weak”. Since they apply only to AEA publications, there remain some journals in which non-disclosure is “not ethically challenged”. The AEA did not respond to requests for an interview on the impact of the new rules.

Just as controversial has been research into fracking, the recently devised technique of blasting water and chemicals into rock to extract natural gas, which some critics fear could contaminate groundwater and lead to earthquakes. In 2012, the University of Texas at Austin withdrew research by its Energy Institute that found no evidence that fracking led to contamination after it emerged that the lead investigator had failed to disclose having received $413,900 as a board member of Plains Exploration and Production, an oil and gas company that invested in fracking.

In the UK, earlier this year the campaign group Talk Fracking released a report into “frackademics”, claiming that the “fracking industry and its PR machine have infiltrated the academic community and skewed the scientific arguments in favour of shale gas”.

But when do accusations of conflict of interest become too broad-brush? Paul Younger, professor of energy engineering at the University of Glasgow, was last year accused by a member of the Scottish Parliament of lacking transparency over his links to an energy firm after he co-authored a paper that suggested that the risk of earthquakes from fracking was lower than had been imagined.

During the controversy, Younger says, he received huge amounts of abuse, forcing him to close down his Twitter account. He even received a death threat that was judged to be credible by the police. He has since turned down a number of public engagements to speak about unconventional sources of gas because of fears over safety and abuse.

The whole controversy was based on a complete misrepresentation of his commercial interests, Younger argues. His research was about land fracking, which is actually “inimical” to the interests of Five-Quarter, the Newcastle-based energy company he then worked for as a non-executive director. Five-Quarter wants to extract gas from rock beneath the North Sea, which would have been made commercially far more difficult by a major expansion of fracking onshore, he says.

He was “flabbergasted” that “talking about something against your interest is accused of being sinister. That sort of nuance gets lost in the noise.”

Younger also makes a wider point. “If the only people entitled to comment [on the benefits and risks of fracking] are people who have no experience of industry”, this lack of expertise will ultimately lead the UK economy to “crash and burn”, he says.

Another question is whether full disclosure would be enough to stamp out bias where conflicts of interest do exist.

According to Nelson, “disclosure is the first step” because if people know that they will have to reveal their interests, “there are some things they just won’t do”. For instance, thousands of academics, including historians, scientists, statisticians and legal experts, received secret funding from the tobacco industry as part of its campaign to spread doubt about the health impacts of smoking; full disclosure would have prevented many from accepting the funding, Nelson thinks.

He also notes that “disclosure makes it possible for the public and press to raise questions”. However, the press’ job is only made harder by US universities’ typical failure to make public the reports of potential financial conflicts of interest that they often require academics to file (although it is possible to use states’ freedom of information rules to find information, Nelson notes). Moreover, disclosure is not, on its own, enough. Ultimately, “you need regulations that ensure the effects of conflicts of interest are minimised and if possible eliminated”, Nelson says.

Even more troubling for the frequent emphasis of anti-corruption campaigners on disclosure is evidence from psychology that it can actually give people a “moral licence” to distort their conclusions (see ‘IOU: the psychology of indebtedness’ box, below). And it does not appear to take tens of thousands of pounds to sway scientific judgement. “Basically, a [free] pen and pencil will do it,” says Nelson.

As far back as 1992, researchers found that doctors in the US started to prescribe certain types of drugs much more frequently after they were treated to an all-expenses-paid symposium in the Caribbean or the sunny West Coast by the manufacturers. Receiving even relatively small benefits “messes you up in a way that you don’t have full control over”, Nelson argues.

This has led some institutions in the US to prohibit gifts outright. In 2010, Stanford University banned more than 600 physicians who were acting as adjunct clinical faculty at its medical school from accepting “industry gifts of any size, including drug samples, under any circumstance”. They were also prohibited from being paid by drug companies to deliver presentations on their products.

It is in medicine that there has been the greatest concern about conflicts of interest – and the most analysis about the potentially distorting impact of industry-funded research. According to the AAUP’s survey, four separate meta-analyses and literature reviews have found that researchers are up to four times more likely to favour a new drug if the research into its efficacy is funded by companies. This could be because companies fund trials only when they think there is a good chance of success, it acknowledges. “But the documented association between funding source and research bias, carried out now across diverse areas of clinical drug and tobacco research, raises serious concerns about possible undue influence on research results.”

Conflicts of interest can also occur when scientists develop a new treatment that does not involve drugs – such as a coaching programme to improve nutrition and fitness – and then give up their academic careers to found companies that sell and research these new interventions. With their financial future pegged to the success of a treatment, scientists become “more and more closed and hostile to [contradictory] data and competing theories”, according to Alex Clark, professor of research nursing at the University of Alberta. A paper he co-authored earlier this year, “Addressing conflict of interest in non-pharmacological research”, published in the International Journal of Clinical Practice, argues that to prevent conflicts of interest in non-pharmacological research, treatments should not be tested by those who design them.

This raises broader questions about the spin-out model, where scientists take their own research from the lab to the market, and potentially become very rich in the process. Does this put pressure on them to not question their own previous findings? “It certainly does where the financial incentives are overly skewed towards a particular intervention,” says Clark. However, he believes that the greater threat to scientific objectivity is the “insidious” pressure academics are under to publish striking results in high-profile journals.

“A few scientists develop the full-blown corporation on the side. But the vast majority of researchers in psychology and medicine don’t do that,” he says. “But we do see [people] cutting corners on the scientific method.”

Yet he adds that these two types of conflicts of interest – relating to money and career – are not, in fact, distinct, because career progression and reputation lead to better-paid and more secure positions. In both cases, careers become pinned to the success of a particular type of treatment.

“That’s not true to the model of science we should be following,” Clark says. And while the public may still largely trust academics and scientists, “opinion can change very quickly”, he warns.

Eric Campbell, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who researches doctors’ conflicts of interest, thinks that one reason public trust in science has held up so far, despite a rise in “the frequency of stories about conflict of interest in medicine and research”, is that the issue still remains “under the radar of the average person”. He also points out that not all readers of newspaper exposés about conflicts will view them as trust-destroying scandals and that, in many cases, journalists have been alerted to the stories precisely because of improvements in transparency in the funding of medical research.

But in non-medical areas, such as agriculture, business and economics, safeguards are weaker, he believes. “Medicine has been at the forefront of managing these interests for 20 to 30 years,” he says. “Other fields have simply not caught up.”

IOU: the psychology of indebtedness

Humans are hard-wired to expect others to reciprocate favours, and even “subtle” acts of benevolence from one person may trigger an unconscious payback from another, a symposium on influence and reciprocity held by the American Association of Medical Colleges heard in 2007.

Using the results of experiments from neuroscience, psychology and behavioural economics, the association set out to explore how industry support for medical research and education might skew results in its favour. It reached troubling conclusions.

In one cited experiment, participants were asked to judge whether they liked a painting. Researchers found that simply telling participants that a company had paid for the experiment, and then flashing the firm’s logo next to the painting during the evaluation, made subjects more likely to rate the painting highly.

“The art experiment suggested that valuation is affected even if there is no monetary gift at all,” said Read Montague, then Brown Foundation professor of neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine. “The moment you touch the valuation system with a gift or favour, things begin to change.”

Evidence from another experiment suggested that disclosure of a financial conflict of interest, commonly seen as a solution, can actually make the problem worse. In the study, one subject – the estimator – had to guess the value of coins in a jar, which they saw only briefly from a distance. A second participant was able to see the jar up close, and then advise the estimator on how they should guess.

When the advisers were paid on the basis of how high (as opposed to how accurate) the estimator’s guess was, they unexpectedly suggested higher amounts when this motive was disclosed, George Loewenstein, professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University, told the symposium.

Disclosure may give a “moral licence” to the adviser to exaggerate in their own interest, his presentation adds. “The only viable remedy is to eliminate conflicts of interest whenever possible, eg, eliminate gifts from pharmaceutical companies to physicians. This should include gifts of any size, because even small gifts can result in unconscious bias.”

Although the symposium focused on financial conflicts of interest in medicine, the findings apply across academia, it found. “Traditional mechanisms for addressing conflicts of interest and ensuring objectivity may not adequately take into account the biological and psychological processes operating in the human brain that can influence judgement and decision-making,” it summarised.

David Matthews

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Under the influence?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login