It came to a head in 1986 with the death of Len Bias, a basketball talent at the University of Maryland who overdosed on cocaine in his dormitory

It is no secret that college is a time of experimentation. Neither is it a secret that the US, progenitor of the global “war on drugs”, cares a great deal about the substances that young people inhale, ingest and inject.

Since the cultural revolution of the 1960s, higher education has been a focal point in our collective drug narrative. As the setting where young people congregate for the first time without parental supervision, university campuses provide a renewable canvas for all varieties of “deviant” behaviour. Students educate themselves, challenge conventions, have sex, make mistakes, drink, fight and, of course, do drugs. They also navigate the varied stages of psychosocial and identity development. For better and worse, drugs are a part of that, too.

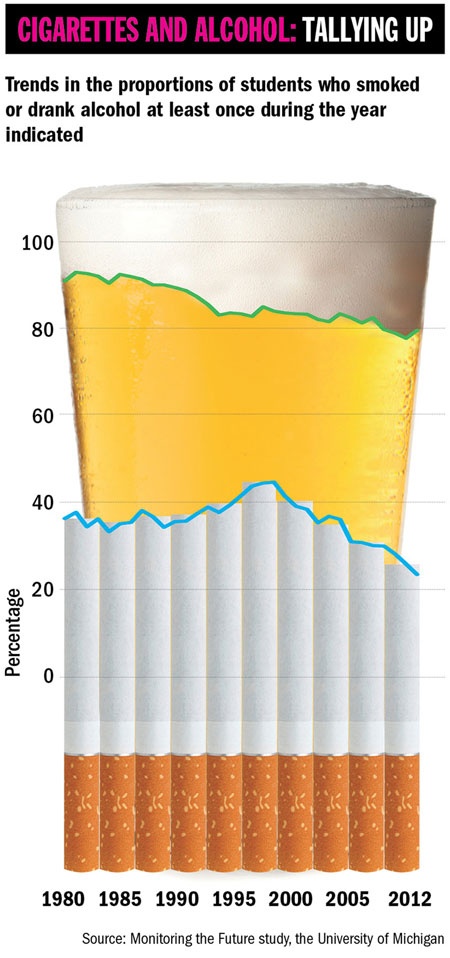

Concern over the “epidemic” of substance misuse in the mid to late 1960s led the National Institutes of Health to launch the “Monitoring the Future” study in 1975 to survey what students were using to get high. Yet, despite the more prohibitive climate that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, a rotating menu of inebriants persisted on US campuses. Marijuana use now almost eclipses tobacco on those campuses; Ecstasy (MDMA) has long supplanted LSD as the hallucinogen of choice, and while the hypnotic sedative methaqualone (Quaalude) has mostly gone, Xanax and a litany of other sedatives remain rife.

Further significant events occurred in the early to mid 1990s that influenced trends that continue to this day. Many “drugs”, such as opiates, MDMA and marijuana, are being rebranded as “medicines”, and increasing numbers of college students are using drugs for alleged functional or “enhancement” purposes. Research suggests that students’ changing attitudes to marijuana in particular, together with the quandary about the use of “brain pills”, are prompting a broad reappraisal that could have future health implications both on campus and across society.

Such reconsiderations would imply that previous cultural and political assessments of drugs were inaccurate. Examined historically, this is probably true. In a recent article for the journal History of Education (“From recreational to functional drug use: the evolution of drugs in American higher education, 1960-2014”), I examined the past half-century of drugs in US higher education, cutting across epidemiological substance use trends, policy milestones, cultural events and the role of institutions. How did we get here? And why is higher education so central to our perceptions about drug use?

In the 1960s, the US government had a complicated relationship with universities and colleges over the rapidly evolving drugs landscape. On the one hand, universities were working closely with the government to advance Cold War-era research projects, including the Central Intelligence Agency’s MK-ULTRA trials to weaponise “psychomimetic” hallucinogens for potential espionage use as a truth serum. On the other hand, campuses were overwhelmed by a surging population of baby boomers who were somehow procuring unprecedented quantities of new or newly popularised substances against a backdrop of the civil-rights movement and conscription for the escalating conflict in Vietnam.

In short, campuses were loci of conflict, drug policies were primitive, and the federal government was caught largely by surprise. Collegiate drug use boomed, spurred by figures such as Timothy Leary, leader of the Harvard Psilocybin and Harvard Psychedelic research projects, and author and drug propagandist Ken Kesey (who coincidentally served as a human subject in MK-ULTRA research while attending Stanford University). After Leary’s arrest for marijuana possession in 1968, Richard Nixon is alleged to have called him “the most dangerous man in America”. Independent estimates of the proportion of college students using drugs range from 15 per cent to 33 per cent for marijuana, and from 2 per cent to 11 per cent for LSD, based on surveys conducted between 1966 and 1968. A crackdown was imminent.

Many point to the Manson murders and the violence-ravaged Altamont music festival as culturally significant moments in the souring of public perception towards drugs and the wider counter-culture. The surge in amphetamine use was also a key catalyst for policy reform, with nearly 10 per cent of all Americans using amphetamines and 1.9 per cent misusing them non-medically in 1970, according to a 2008 article in the American Journal of Public Health by Nicolas Rasmussen, “America’s first amphetamine epidemic 1929-1971”. In 1971, President Nixon declared the “war on drugs”, persuading Congress to pass the Controlled Substances Act in 1972, and establishing the Drug Enforcement Administration the following year.

These moves marked the beginning of a prohibitive and punitive drug policy era that became increasingly severe throughout Ronald Reagan’s administration. It came to a head in 1986 with the tragic death of college student Len Bias, a heralded basketball talent at the University of Maryland who overdosed on cocaine in his dormitory less than 48 hours after being selected to join National Basketball Association champions the Boston Celtics. In almost any other year, the loss of a single, albeit transcendent, college athlete would have been treated as heartbreaking but fleeting sports news; 1986, however, was a pivotal election year and, with the emergence of crack cocaine as an urgent public health threat, politicians were competing to develop tough approaches to drugs. These conditions led to the legislation that would become the Anti-Drug Abuse Act.

The act infamously introduced “mandatory minimum” sentencing guidelines and quantity thresholds for drug offences that many regard today as arbitrary and racially inequitable. With the benefit of hindsight, the merits of these policies – known in some circles as the “Len Bias laws” – were at best highly questionable given the unconscionable rates of incarceration in the US. At worst, the act and its subsequent amendments may be viewed as economically regressive and socially irresponsible.

Whichever view you take, years after its passage it was revealed that the act was established under false pretences because the expert witness responsible for setting the crack and powder cocaine quantity triggers was convicted of perjury for falsifying his pharmacology credentials and lying under oath during his testimony to the House of Representatives Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control. Eric Sterling, former counsel to the US House Judiciary Committee, said in a 2011 interview that “hundreds of thousands of people would have never gone to jail if Len Bias had not died”.

In hindsight, Bias was a bellwether of what drug policy scholars and social critics refer to as “the estrangement of science and policy”. Discussing the US’ treatment of illicit drug use in 1996, John Falk, a research psychologist and pharmacologist at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, wrote: “Policy can be a closed, self-validating system, almost impervious to scientific facts…[and] can be dismissive of facts and alternatives simply on the grounds that they are distasteful.” Such sentiments rang true, especially in the “just say no” era of US drug policy, which erred critically by painting both drug users and substances with wide brushstrokes that belied the plurality of the drugs themselves.

While the 1970s and 1980s were dark decades for institutional research involving illegal or “controlled” substances, the mid to late 1980s was a momentous time for the advancement of the science that was to define the next acronym-strewn evolution of the collegiate drug narrative.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) launched an entire field of brain tomography research and signalled what Marcus Raichle, professor of radiology, neurology, neurobiology and biomedical engineering at Washington University in St Louis, has termed the “birth of cognitive neuroscience”. Subsequent advancements in epigenetics cast new, empirical light on age-old debates, enabling more accurate appraisals of health risks, including the risks of drug use. For the first time in history, researchers could study brain function and drug pharmacokinetics in real time – and new substances were emerging to test the boundaries of the law’s punitive prohibitions on drug use, making volunteers easier to recruit again.

However, as before, the worrisome habits of college students would hasten the reaffirmation of legal and political boundaries. Take, for example, Ecstasy, which has been the dance drug of choice since the mid 1980s. It is wildly psychoactive and often dangerously adulterated with unknown additives when procured illicitly at festivals or raves. Yet, in therapeutic settings, controlled doses of MDMA have demonstrated clinical promise in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and other conditions.

John F. Kennedy was injected with a proprietary amphetamine serum to overcome laryngitis before his first debate with Richard Nixon in 1960

The duality of chemicals that can be beneficial in clinical use and harmful when misused is nothing new. It is also true that while some drugs, such as caffeine, are relatively benign, others are just awful (methamphetamine – “crystal meth” – comes to mind, as does desomorphine, the flesh-eating opioid known in Russia as “krokodil”). But as contexts change, the legislative fate of new drugs is usually determined by the perceived balance of its particular risks and benefits at the moment of its emergence.

This, again, is why college students are important.

After illicit Ecstasy began circulating in nightclubs in Dallas, and then spreading across US campuses, it hardly stood any chance of retaining clinical viability. MDMA was swiftly declared a “Schedule I” controlled substance in 1985, alongside marijuana, heroin and LSD, with no accepted medical use.

As the stigmatisation of “drugs” continued through the 1990s, the US also experienced a growing problem with the misuse of legal drugs. Prescriptions of sedative and anti-anxiety medications, such as Xanax, Valium and benzodiazepines, rose by an average of 17 per cent a year between 2006 and 2012. The US’ 5 per cent of the world population currently consumes 97 per cent of the planet’s stock of opioid pain medications, such as Vicodin and oxycodone. And when it comes to prescription stimulants, college students don’t just reflect wider national trends, they are setting the pace.

Again, the misuse of prescription drugs is nothing new. Amphetamines and other stimulants have had known functional use in academic, employment and military settings since soon after their synthesis and early popularisation in the 1920s. Benzedrine was supplied to Allied troops in the Second World War (to compete with the German military amphetamine Pervitin) and it fuelled Jack Kerouac’s composition of On the Road. Long before anabolic steroids and modern sports doping scandals, amphetamines were a tolerated and ubiquitous presence in professional baseball and cycling. And a singular and historically significant instance of performance enhancement saw John F. Kennedy injected with a proprietary amphetamine serum to overcome laryngitis before his first debate with Richard Nixon in 1960 – a debate that swung history.

The revised third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, released in 1987, expanded the diagnostic criteria for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, making it the most diagnosed neurobehavioural disorder in the US, according to a 2010 report in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (“Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children – United States, 2003 and 2007”) . Consequently, prescriptions for stimulant medications skyrocketed, with production of Ritalin increasing 900 per cent between 1990 and 2000, and Adderall production ballooning by 5,767 per cent between 1993 and 2001. Currently, almost one in 10 American schoolchildren is diagnosed with ADHD, and they are taking their medications with them to college.

Prescription stimulants are central to an “enhancement” drug paradigm that is becoming increasingly salient in higher education. Whereas the “prevention” of recreational drug use may characterise the institutional approach to collegiate drug use over the past half-century, the coming decades will probably see growing concern over the equitable attainment and ethical use of drugs for so-called enhancement purposes.

The landscape of higher education has arguably never been more competitive, and any former temptation for students to “turn on, tune in and drop out” is being supplanted by a compulsion to turn on and stay on – for hours, in an augmented, uninterrupted state – so you don’t drop out. It’s worth saying that the distinction between “recreational” and “enhancement” drug use is a complex one, and the categories are not mutually exclusive. It’s also unclear whether stimulant medications are even efficacious for individuals who don’t suffer from ADHD; at best, the available evidence suggests that the cognitive benefits of prescription stimulants are fleeting and depend on both the individual and the task being undertaken. What is clear, nevertheless, is that the college students who use them – either licitly or illicitly – overwhelmingly think that they work. This creates further demand, among both those who believe they may have ADHD and those who do not.

Regardless of efficacy, some institutions, such as Duke University, have begun explicitly to regard the misuse of alleged cognitive enhancement drugs as an issue of academic integrity. In other words, it’s cheating. Such policies correctly assume that future enhancement technologies – pharmacological or otherwise – will improve. They also acknowledge that many students are informed, rational consumers willing to strike a Faustian bargain for desired academic or occupational outcomes. Even if stimulants’ advantages are fleeting (or perhaps harmful in the long run), some students will take the view that it’s worth breaking the law to get into law school, or misusing medications to get into medical school.

This represents a new twist on why university students will always be centrally important to society’s evolving relationship with drugs. Students represent a tremendous quantity of economic human capital that the incautious use of drugs could spoil – and dropping out, addiction and myriad psychological and physiological risks are hardly consistent with the mission and purpose of higher education. But what if productivity could be augmented without risk? What if the optimal deployment of the right kinds of drugs into our universities (and professions) could actually promote human capital? If, say, a cure for cancer or the discovery of infinitely renewable energy could be hastened by judiciously hacking our finest minds, would it be unethical not to enhance?

A parallel might be drawn with contraception. Birth control issues were paramount on college campuses in the early 1960s, and unplanned pregnancies were a great cause of anxiety and dropouts among both women and men. In other words, they were detrimental to the development of human capital. As more and more states legalised the Pill over the years, dropout rates fell significantly.

Ultimately, if the relationship between students and drugs serves as a harbinger of broader trends and drug policy shifts, then it is a relationship worth examining very closely. Take, for example, cannabis. The legislative creep in the US towards marijuana decriminalisation (and even, in four states, legalisation) would arguably not have even the modest momentum it enjoys today if it were not for a generation of current lawmakers who got high in college.

This is not to suggest that current and future generations of college graduates will go on to clamour for universal access to Adderall in adulthood. But we should recognise the potential for a gradual erosion of draconian drug prohibitions as a different generation of college students, who consume different drugs, begin to swell the electorate.

We should also consider the potential for new avenues of legislation to err in the other direction. It is not clear what longterm effects – from either health or policy perspectives – will emerge from the proliferation of “study drugs” and “brain pills” among college students. US campuses today face a confounding situation where 10 per cent of the student population is medicated with powerful drugs that may or may not be advantageous for almost anyone, but that are purportedly dangerous for everyone.

Science and empiricism must weigh heavily in future determinations of “responsible” drug usage and policy.

Fortunately, with the moratorium on research involving banned substances receding, new research studies are beginning involving psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms), MDMA and cannabis at institutions including Johns Hopkins University, the University of Arizona and New York University. And in 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act, which corrected the imbalanced sentencing guidelines for crack cocaine that were hastily set during an era of prohibitive zealotry. We have good reason to hope, then, that future reforms will also be informed by concurrent realities about the efficacy, risks and ethics of drugs that can both help and harm.

Too toxic for the mainstream: ‘censorship’ stymies research

Research into illegal drugs such as Ecstasy, LSD and cannabis remains “almost impossible” in the UK, according to David Nutt, the Edmond J. Safra chair in neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London.

Nutt – who was famously sacked as the government’s chief drugs adviser in 2009 after arguing that alcohol was more harmful than any other drug – says that since LSD was banned in the 1960s, there has been only one clinical study of the drug in the entire world, published last year by a Swiss group.

Sourcing illegal drugs for research is “a whole world of complexity and pain”, while obtaining the necessary, annually renewable licence is expensive and time-consuming. Although Nutt was recently granted permission to run the world’s first study of the effects of LSD using brain imaging, “the fact that we have managed to work our way through this bureaucratic jungle is testimony to us. Most people just can’t be bothered,” he says.

An even bigger problem, he adds, is the reluctance of mainstream funders to support studies involving illegal drugs. Both the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust declined to fund the LSD study, leaving Nutt reliant on a £100,000 grant from the Beckley Foundation, a small-scale funder set up specifically to back research into psychoactive drugs. However, Nutt had to resort to crowdfunding in March to raise the £25,000 he needed to finish analysing the data (he raised that sum in 36 hours and nearly doubled it within a fortnight, receiving donations from people in 46 countries).

Meanwhile, Nutt’s pioneering brain-imaging study of the effects of hash and skunk was funded by the television company Channel 4 and broadcast in March. The channel also funded Nutt’s study of the effects of Ecstasy, which it broadcast live in 2012.

“The issue [with ‘traditional, kosher’ funders] is always that these are recreational drugs,” he says. “That label is so powerful that I think it scares people off. They think that if we are doing research on recreational drugs, we are therefore encouraging recreational use.”

This squeamishness extends to fellow scientists, Nutt says. “I would argue that you can’t study consciousness without using these kinds of drugs. But I have approached the top experts in this country and the world to work with us, and they have said [it is] too risky for their reputations.”

He says the current state of affairs is particularly pernicious because studies carried out in the 1950s and 1960s indicated several potential therapeutic benefits for psychoactive drugs, such as in treating alcoholism. A pioneering study that Nutt’s team recently conducted into the neurological effects of psilocybin – funded by the Beckley Foundation and Imperial College – indicates that it may be useful in treating depression. The MRC has agreed to fund a clinical trial to explore that potential – but Nutt notes that “funding clinical trials is much less controversial [than funding basic research into drugs] because it is helping people who are ill”.

He points out that, even if therapeutic uses are proved, there are currently only four hospitals in the UK permitted to hold supplies of psychedelic drugs – despite there never having been an instance of supplies being misdirected or stolen for recreational use.

He likens the “censorship” of research into illegal drugs to the Catholic Church’s declaration in 1616 that heliocentric views of the universe were heretical – which, in his view, in effect banned the use of the telescope.

“But in terms of the amount of wasted opportunity, it is way greater than the banning of the telescope,” he adds.

Paul Jump

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login