As academics wake up on Christmas Day, many will find their stockings bulging with books written for a general audience by colleagues from different fields. But it is just possible that the pleasure of learning something new, in lively, engaging prose, will be tempered by a pang or two of jealousy.

Attractively presented, energetically marketed and widely read, “trade books” are, in some ways, everything that standard academic publications are not. They offer scholars a route into literary festivals, newspapers and even television, allowing them to inform public debate while, potentially, receiving a significant supplement on top of their university salaries.

Career requirements mean that most younger academics “have to do books for peer-review publishers”, concedes Andrew Franklin, founder and managing director of Profile Books, whose authors include classicist Mary Beard and political scientist Francis Fukuyama. Yet when they “reach a certain stage in their careers…they very often choose to switch to trade publishers, where there are advances...We publish some academics who look to at least double their academic salary by their writing.”

Yet while trade books might intuitively seem easier to write than meticulously researched, heavily referenced texts designed to withstand the scrutiny of immediate peers, the challenges are many for those intent on writing the stocking fillers of Christmas 2023. So to help academics find their way down readers’ chimneys, Times Higher Education has spoken to a range of senior publishing figures about what they are looking for – and what authors definitely need to avoid.

Academics with such ambitions would be wrong to assume that they necessarily have to focus their attentions on standard trade publishers. According to one senior figure (who asked to remain anonymous), “the publishers with the most consistent success developing scholarship into trade books for a wider market are non-profit university presses, including Chicago, Yale and Oxford.” But both kinds of publishers have very similar criteria for their trade rosters.

Casiana Ionita is publishing director at Penguin Press, whose authors include physicist Carlo Rovelli, Ukrainian-American historian Serhii Plokhy and Katie Mack, author of The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking), a surprisingly lively study of all the different ways the universe might collapse at any time. Trade publishers, she argues, are looking for academics willing to brave the minor caveats of their peers in order to “bring all their knowledge to bear and to be as bold and broad as they can, rather than exploring a slice of a slice of a slice of a field. Even if a book starts quite specific, it has to make a much bigger point that feels relevant to conversations happening in the world.”

Writers of trade books, Ionita goes on, need to “start with something really gripping, instead of building and building over many pages, explaining the field, describing what this and that person has done. Get to the point really quickly. We are all so busy, so you want to grab the reader by the neck as quickly as possible. Otherwise, they won’t keep going.”

Equally important, though less often discussed, is to “really land the ending – something even journalists sometimes find difficult. You spend so much time writing the book and getting into the nitty-gritty, and then readers can just feel ‘And now we have come to the end.’ Or there’s a summary, which is quite dry. The end needs to be as memorable as the beginning.”

Many people working in disciplines ranging from climate science to critical race theory evidently, and often explicitly, aim not just to describe the world but also to change it. But “psychologically, the most recent things are what stays with us,” Ionita notes. Hence, the trick is to pack “the emotion you are trying to convey…into those last few pages and send the reader off with those vibes. Maybe you can have another anecdote or a very memorable last sentence – which is as valuable as a very memorable first sentence.”

As an example, Ionita cites Rovelli’s bestseller Seven Brief Lessons on Physics. This concludes with the words: “Here, on the edge of what we know, in contact with the ocean of the unknown, shines the mystery and beauty of the world. And it’s breathtaking.”

Of course, to write a sentence like that requires a certain knack with words.

“Trade writing is about flair,” says a former commissioning editor at an independent publishing company, the majority of whose books are written by academics. And many academics don’t possess that kind of flair, she concedes, recalling being told by the literary editor of a major UK broadsheet newspaper that he almost always regretted asking academics to review books for him.

“A journalist would take an emotive subject, such as child prostitution or modern-day slavery, and tell it through a series of stories, characters they develop, worlds they take you into,” she reflects. But academics, in her experience, are rarely willing or able to adopt such an accessible approach.

Nonetheless, there are other ways to produce the “wow factor” that is “always good for a trade book”, the editor says. “I’ve not heard that story before”, is one reaction that the editor prizes, “Or ‘Oh my God, how did you get access to that?’ – or even ‘I can’t believe they are publishing a book on that subject: it’s outrageous!’”

For Ed Lake, publishing director for non-fiction at Weidenfeld & Nicolson, considerations of content are very different for trade books compared with purely academic writing, where “the basic question…is generally: what is the gap in the scholarly literature and how does the present work fill it? That way of thinking isn’t especially helpful for trade writing. There, the question is always: ‘What are you going to give me? How will this change my world? What is the exciting surprise here?’ Gaps in the literature don’t matter unless they can be construed as longstanding and fascinating mysteries.”

Trade books can also benefit from the presence of “bad guys, or, anyway, interesting characters”, Lake adds.

Such requirements typically quash any aspirations that junior academics might have to turn their PhD theses into trade books since, as Profile’s Franklin puts it, doctoral work is aimed at revealing “things that no one else knows” and demonstrating “that you are the expert, that you have every i dotted, every t crossed, and that you have covered every inch of the archives. That is a million miles away from thinking: ‘How can I reach and persuade and educate and inform and delight my audience?’”

Giuseppe Laterza is chairman of Editori Laterza and also oversees the family-owned Italian company’s output of general non-fiction, most of which is written by academics. He agrees that trade books have to express forceful views on large topics. Although they need to “convey someone’s individual research” and have “something new to say”, they often need to range beyond the author’s core areas of expertise and include more second-hand material. They also have to make bold points; he always overrules authors who propose tentative titles for their books along the lines of First Thoughts about Possible Conclusions Concerning…

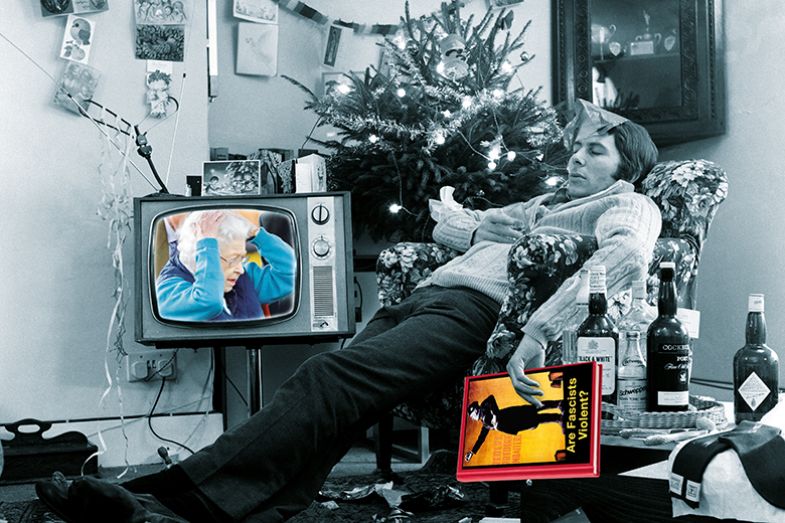

It is also important for academic authors to remember that most people don’t keep up with the latest scholarly fashions. Laterza offers an example relating to the study of Italian fascism. Because there has been a recent trend for historians to stress the importance of consensus, he has had academics pitching book ideas to him because they “had found a new exciting archive which provides all the evidence to show that fascism was a regime based on violence”. Yet the general public, as he has to politely point out, has never doubted that fascism was a regime based on violence.

Julian Loose, editorial director at Yale University Press London, also points to a gulf between debates in the academy and “the real world”, which means that “lots of exciting new subject areas and radical interdisciplinary approaches that work on campus don’t make it across to the high street...[Even] when we see potential in a project, there’s often a need to shake up the proposal, to shape a narrative or sharpen an argument, to insist on the difference between the exhaustive or tight focus approach of a thesis and the more engaging form of a non-fiction book.”

So how should would-be trade authors approach publishers? In putting together a proposal, the anonymous former editor urges academics to think of it as a business plan: “You are saying to the publisher, ‘I want you to invest several thousand pounds in my idea’, so it has to make a convincing case. If it’s a more scholarly book, what makes it a unique offering has to be very, very clear. If it’s a book you hope will also be adopted on courses, you need to be able to demonstrate what those courses are and why the books already being used aren’t sufficient. If a book is positioned as relevant for policymakers, what’s the evidence that it’s going to fill the niche it aims to fill? If it’s a book for more general readers, the question is: what general readers? What other books are they reading?”

This issue of defining the audience – and, therefore, pitching the tone and argument at the right level – is a particularly vexed issue. Especially in the social sciences and humanities, as the former commissioning editor points out, academic training is focused on developing a writing voice that is “very precise, quite dry, not polemical or colloquial”: qualities that are “not seen as typical of sound academic writing”. This academic voice is perfectly appropriate “if you are writing for other scholars. They are already won over: they are reading your book as part of their job. They have to read it because they want to cite it.” To engage with a wider readership, however, “you need to borrow – while still remaining academically rigorous – a different kind of voice”.

Franklin often encounters academics who fail to make that leap, submitting manuscripts that remain “too narrow and academic” for a general readership. However, he also encounters the opposite extreme, when academics “write the most appallingly patronising stuff” because they fail to grasp that, far from being tabloid readers, “the only people who read books by academics are graduates or those who have self-educated themselves to graduate level. They are used to reading books that are intellectually rewarding and challenging.”

The worst proposals, Franklin says, veer between these two extremes, mixing details incomprehensible to non-specialists with blatantly patronising passages in a way that is “insulting to everybody”. Such failures typically arise when authors “haven’t read enough outside their own field. They are probably not very good lecturers either.”

So how should trade authors picture their readers? Since there is no such thing as a standard “general reader”, Ionita suggests they “imagine a bit more specifically who they have in mind. It has to be someone intelligent, curious and interested, but it’s quite helpful to imagine someone in particular – maybe your partner, your mum or your student – and to have that image to ground you, because otherwise it is very easy to default to your peers, who are always around.”

It is here that some trade publishers offer authors substantial support in thinking through the perennial challenge of writing for a wide readership: different people inevitably have different levels and areas of knowledge. One will feel mystified if you don’t explain who Harold Wilson was. Another will feel patronised if you add a phrase such as “twice prime minister of the United Kingdom between 1964 and 1976”. Over a long text, both over- and under-explaining can rapidly feel alienating. There is never a perfect solution, but Ionita sees it as “part of the editor’s job to go through line by line, flag things up and have those conversations through several rounds of editing – something quite unusual in academic publishing. The editor is someone who is reasonably interested and curious but doesn’t know that much...We are modelling that kind of readership for the author.”

According to the former commissioning editor, authors with a lot of teaching experience tend already to “have another voice, which enables them to take quite complex ideas and explain them to an audience that has never come across them before. If you’ve had to stand in front of a class of bored 18-year-olds and introduce them to some philosophical idea or theoretical approach, you have to have lots of different tools in your toolbox.” But since there is generally “more value placed on good teaching” in the US than in the UK, she has found that American scholars often find it easier to draw on an established teaching voice in their writing. She sometimes found it helpful to tell those lacking such a voice that writing a trade book is a bit like explaining their ideas to someone at a dinner party.

Ionita agrees that an author’s conversational voice can sometimes be the key to developing an authorial voice that resonates with the general reader.

“When you speak to an author, they do have a voice,” she reflects. “So it’s about getting that in writing…Quite often I will work on the first few chapters to make sure the voice is there, and then they can continue with that.”

Even once they have got the basic voice right, Ionita warns academic authors about the dangers of excessive quotations: “In academic writing, quotations are used almost as a crutch and a way of showing you have read everything and are familiar with the field. But having long block quotations is just deadening for a trade book.”

Another academic habit that is hard to break is addiction to footnotes, and a question much asked of trade publishers is whether authors can have as many notes as they like. The answer is “within reason”. Like most of the other people interviewed for this article, Franklin is “happy to include extensive endnotes”, even if they form up to 10 or 15 per cent of the total length of the book. Moreover, he insists on adequate referencing. He recalls a recent proposal where the author mentioned “tourism experts” – a phrase he calls “completely unacceptable in a book by an academic…You have to say who the person is, why they have authority if that’s relevant and then footnote it...I am keen that the reader, and particularly fellow academics, can follow up and find out what the sources are.”

Others, however, caution against over-referencing. Laterza tells his authors that “everything you say can be related to some other book, but the reader gets tired if you splatter every sentence with references.”

As for methodology chapters, if an author insists on one, he tells them that these have to go at the end of the book because “the general reader is not interested”.

Laterza’s other bugbears include academics who produce books twice as long as they have signed up for; those who deliver their manuscripts many years late (and then often expect them to be published almost instantly); and those who create endless work for their editors by using “enormous sentences of 60 or 70 words, sometimes without punctuation”.

Another understandable failing is flagged up by Alan Thomas, editorial director at the University of Chicago Press. “Many writers – especially scholars but also journalists and others – have trouble being selective enough with their research findings to fit them to a book’s requirements: [brisk] pacing, a well-shaped argument, reasonable chapter length,” he says. “There’s always the temptation to treat the book primarily as a vessel for hard-won research, but the book is then more likely to be shelved for mere reference than read and engaged with.”

Thomas reminds authors that “there are often other ways to use the bits that are so painful to cut: save them for related essays, lectures and so on”.

“Publishing the results of their research in established scholarly genres is what scholars should be doing,” Thomas agrees. In that sense, “it’s absurd to lament career incentives that are at odds with the needs of publishers of commercial books”. However, he is convinced that the divide between traditional academic and trade writing is not necessarily a wide one.

Although it is part of his role as an editor to help writers of every kind “recognise and overcome lots of bad habits”, he is still convinced that “a piece of scholarly writing can be consequential and absorbing, even moving, while working within academic conventions. And I know from experience that scholars can reach a wide public without sacrificing rigour or extensive endnotes.”

The issue, according to Ionita, is that, at root, some academics don’t truly want to reach a wider public. In signing up authors, she is always wary of academics who are “a bit conflicted about writing a trade book” and “really want to speak to their peers more than general readers”. Even when she manages to steer such authors into writing in the way she requires, they often prove unwilling to “go out and take part in public debates”, which makes it much harder to mount a publicity campaign.

Major trade publishers put much time and effort into marketing their books and, understandably, want their authors to play their part. Annabel Huxley, head of publicity at Penguin Press, advises academic authors “to think hard about radio/broadcast interviews and to practise how to present the book to listeners who might know nothing about the period or story in a limited period of time, pulling out key points with examples, in layman’s language”. Part of the trick is to use “voice intonation to convey [the author’s] own fascination and excitement with the points they are making”.

Authors should also consider approaching newspaper and magazine editors with article ideas based around “contemporary angles or parallels with their thesis, characters or insights”, Huxley adds. “Having fun with what the headlines might be – the provocations – is a great way to start.”

Many successful trade authors are driven by that sense that engaging with the wider world is fun. Of course, not all academics have the temperament or areas of expertise suited to writing trade books. And it is always going to be more of a challenge to write something that thousands of people will want to read than a journal article that even your own mother is likely to ignore. Yet for those with a gift for writing tomes that aren’t too heavy for Santa’s sleigh, the sky’s the limit.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How to write the next seasonal bestseller

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login