“When you work in this area, you see death everywhere and realise how life is on a knife edge at any point. You become hyperaware of it and I have to work very hard, especially now that I have a family, to do normal things and try and forget that at any point the car could crash or the tree fall over or someone get a lump…”

Kate Woodthorpe is deputy director of the University of Bath’s Centre for Death and Society – whose members, according to its director, John Troyer, are united in their interest in various aspects of the “related but different” themes of “death, dying and dead bodies”.

Troyer, the son of an American funeral director, is a surprisingly cheerful character rumoured to wear shorts in all weathers. But death studies is a pursuit that can raise some eyebrows with colleagues who don’t like to think about such things.

“Back here when I started,” recalls Woodthorpe, “there was a joke about ‘the death squad’, [and suggestions] that we are quite strange people to be interested in such a niche topic. And you think: ‘Hang on, it’s not that niche! What do you think’s going to happen to you – and everyone you know?’”

The centre – which does not have a physical building – was set up in 2005 and used to offer a foundation degree for funeral directors, covering both business skills and the history of funerary ritual and issues of cultural diversity. But since the university cut back on foundation degrees, its members have continued to research death-related issues while teaching on more general courses; Troyer offers an undergraduate module on the sociology of death.

Since it forms part of Bath’s department of social and policy sciences, the centre’s members maintain a broad commitment to consultancy, public education and modern, real-world issues. For instance, former director Tony Walter, who is still a professor of death studies at Bath, edited a 1999 book on The Mourning for Diana and now explores topics including “the role of angels in mourning” and “how the internet shapes dying and grieving”. Troyer’s interests include the Aids epidemic, the disposal of dead bodies and organ donation, while other centre members look at the experiences of bereaved parents and the international trade in body parts.

For her part, Woodthorpe has previously studied how people use cemeteries and commemorate the dead, but now she focuses on how they plan and pay for funerals. This has a practical output in the form of recommendations about how the government should assess eligibility for state support for funeral expenses.

“It’s better that people are aware and informed [about death],” she explains. “We all have a responsibility for letting other people know what we would like to happen [after our own deaths]. Otherwise, it’s just landing it on them to work out.”

In retrospect, Woodthorpe traces her interest in death back to the fact that she had “four friends who died in a car crash when I was 17, just before we left school, and then my gran died very unexpectedly a couple of weeks later”. Having “a lot of death around” and “witnessing grief in its rawest form among friends and their families” gave her “a hyperawareness that death can and does happen, and that there’s no need to shy away from it”. She now believes that “academics have a bit of a duty to get these very difficult and painful things out into the public, to make people aware”. So much so that she has even chosen to speak openly about her experience as a mother of a one-year-old child with a life-threatening condition.

Topics like these can obviously be disturbing for academics and students alike.

Another example is the work of Christine Valentine, a member of the centre who did her PhD there in its early days following a career as a psychotherapist. Much of her research has examined “how people cope with very difficult deaths” and one project involved 100 in-depth interviews with people who had lost family members with alcohol or drug addictions.

Such “bad deaths” have a number of specific features, suggests Valentine. They are often undignified and “usually complicated because families will…to some extent have lost the person already” because of their addiction. The stigma attached to them “makes such deaths hard to talk about”, especially as surviving family members often experience “a lot of guilt, because they have failed to get the dead relative off their [alcohol or drug] habit…That was a fairly big theme.”

Furthermore, the majority of such deaths involve a criminal investigation or an inquest, and officials can behave with extraordinary insensitivity. Valentine cites the case of “a couple who ran a post office, where the police went in and announced the death of their son in front of customers”. Equally callous is much coverage of drug-related deaths in local newspapers, she adds.

The outputs from Valentine’s research included guidelines (jointly published with the Economic and Social Research Council and the University of Stirling) for those whose work brings them into contact with people bereaved through substance misuse. It also led to a 2017 edited collection titled Families Bereaved by Alcohol or Drugs: Research on Experiences, Coping and Support. Yet despite the clear practical value of the project, and having “coped with difficult bereavements myself”, Valentine found the stories she heard “very, very painful” and notes that she was “really knocked back” by “the complexity of the bureaucracy and [a sense of bereaved] people falling into gaps”.

Woodthorpe has also struggled with the emotional difficulties of such work. In a 2009 paper published in Mortality, “Reflecting on death: The emotionality of the research encounter”, she recalls how “observing children’s graves, particularly if they had been born in the year of my birth, or witnessing parents around my age attend a grave, often moved me to tears. On one occasion I was so touched by a man’s intense nurturing of a flowerpot by a grave…I had to leave the cemetery for a short while.”

Despite the somewhat taboo status that death still retains even in academic circles, Bath is not the only UK university where associated topics are researched and taught. The University of Winchester, for example, runs a distance-learning MA on death, religion and culture.

This is taught by Christina Welch, a senior fellow in the department of theology, religion and philosophy, alongside a philosopher and a theologian. Most of the dozen or so students who enrol each year, Welch says, work in death-related fields, as counsellors, nurses, funeral directors/celebrants, or “death doulas” or “soul midwives”, who help people to “die well”.

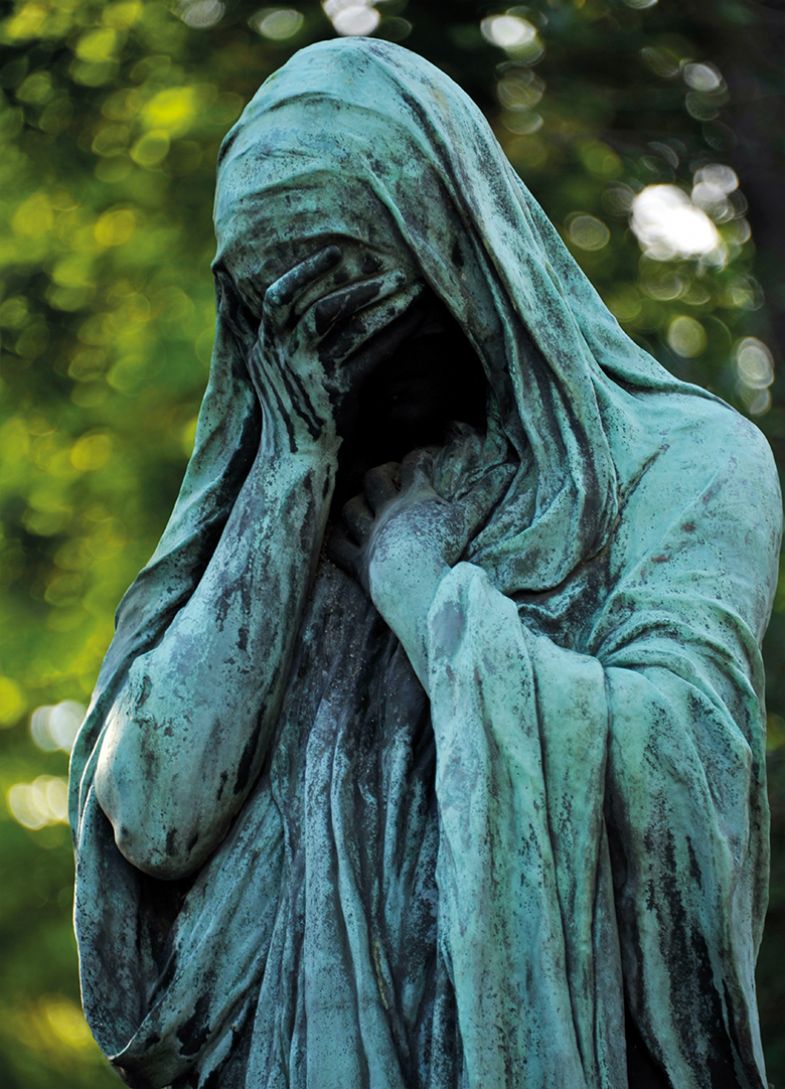

But much of Welch’s material is less vocational than cultural, and includes two of her own current research interests. One is the “carved cadaver sculptures” of Tudor England, which memorialise prominent figures as naked, emaciated corpses or “as if gasping their last breath”. In a spirit of “experimental archaeology”, Welch has commissioned sculptor Eleanor Crook to make one “to see how it was done”, although it is not modelled on anyone in particular. “Eventually, it will be part of an exhibition on these memorials that I aim to tour around some churches,” she says.

The other research theme that feeds into her teaching is artworks on the Death and Maiden theme, in which death is portrayed as a man grasping – and so snuffing the life out of – an often highly eroticised female figure. Her interest in the sexualisation of death also extends to a more modern example: the extraordinary phenomenon of “erotic coffin calendar art” produced by a couple of coffin manufacturers as an improbable marketing tool.

Meanwhile, back in Bath, Troyer’s description of his final-year undergraduate module on the sociology of death, which about half of each year’s sociology cohort opt to take, makes clear to students that it is “an academic unit, not therapy. Students who have been bereaved or are facing life-threatening illness in their family should consult me before starting the unit.”

Some of the weekly topics his course description goes on to list sound, at first glance, fairly abstract; examples include “Death and the biopolitical social turn” and “The definition of death: hearts, brains, and politics”. Nonetheless, Troyer – who has directed the centre since 2015 – insists that strong emotions often emerge in the 100- to 200-word “weekly memos”, in which he asks students to provide “a lively conversation with the reading…as personal or as academic as you like”.

Every semester, he says, “I’ve had students write about the death of a family member, often a parent…It becomes therapeutic, but they are engaging with the material we are covering in class and relating it back to what happened. In many cases, they had honestly never talked about it to anyone before.”

Even more striking are some of the emails from former students that Troyer occasionally receives out of the blue, letting him know what his course meant to them. In one case, a Muslim woman told him about being called upon to help prepare the body of a cousin’s wife who had died of breast cancer. “I want you to know that taking the class helped prevent me from freaking out when I touched the body,” she told him.

Another time, a devout evangelical Christian student wrote about her involvement in the decision to switch off the life support of her brother’s sick child. Taking the class, she assured Troyer, had helped her talk to her brother and sister-in-law to “prepare all of us in making the decision”.

In introducing the course to students each year, Troyer points out that it is likely to be “the most focused period of time you spend in your lives thinking and reading about death”. His hope is that it will help them prepare for things that we all eventually have to face. The responses he receives suggest that, whatever squeamish academic colleagues may make of it, there is much to be said for taking death out from behind the curtains.

后记

Print headline: The dead zone