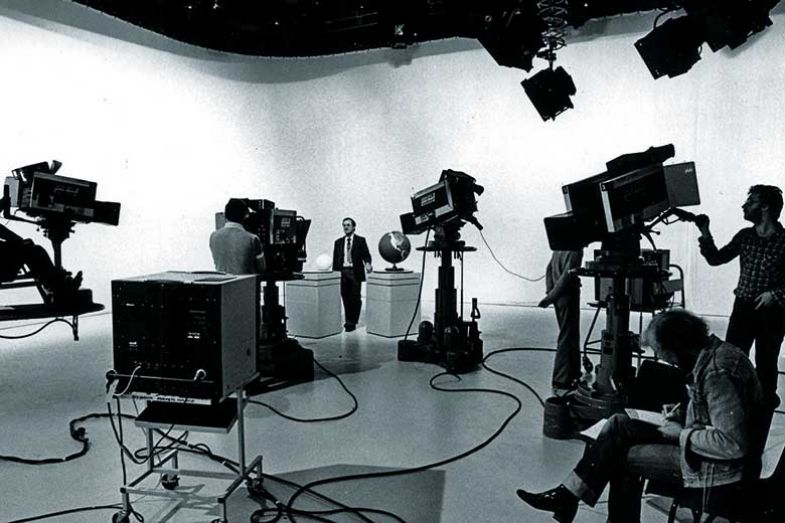

The Open University was the first of its kind, offering flexible distance learning to anyone who wanted it, regardless of previous qualifications. It quickly became an integral element of the higher education landscape and was, for decades, the only alternative in the UK to the campus-based, professor at the front of the classroom style of teaching.

The OU may no longer broadcast teaching materials on television in the middle of the night, but its model – and its philosophy – has stood the test of time: the university is marking its 50th anniversary this year. While this is undoubtedly cause for celebration at the OU, has the institution over these five decades had an enduring impact beyond its own activities on higher education more widely? And, as the popularity of studying for a degree part-time continues to nosedive in the UK, and as many more universities develop their online distance-learning offerings, does the OU have a sustainable future?

Sir John Daniel, the OU’s third vice-chancellor, cited the proliferation of “open universities” around the world that followed the foundation of the Milton Keynes-based OU in 1969 as evidence of its wide-reaching influence.

“In the early ’70s, it made a big splash internationally. Developing countries were looking for ways of expanding higher education at low cost,” said Sir John, who led the OU between 1990 and 2001. There are now more than 50 open universities around the world, including such places as China, India, Cyprus and Sudan.

“I remember as v-c that I didn’t have any authority over all these institutions, but they looked to the OU as their model and their inspiration,” Sir John said.

The potential of using distance learning to educate people who were too poor or lived too remotely to access traditional campus universities was one of the key attractions of the OU model around the world. But just as crucial in entrenching its influence were the impressive quality of the graduates that it produced and the strong reputation of its teaching.

For John Brennan, emeritus professor of higher education research at the OU, the big achievement of those early years was rapidly establishing academic credibility. “Given that there were no entry qualifications – anyone could do any course – it’s remarkable that it achieved such a good reputation so quickly,” he said.

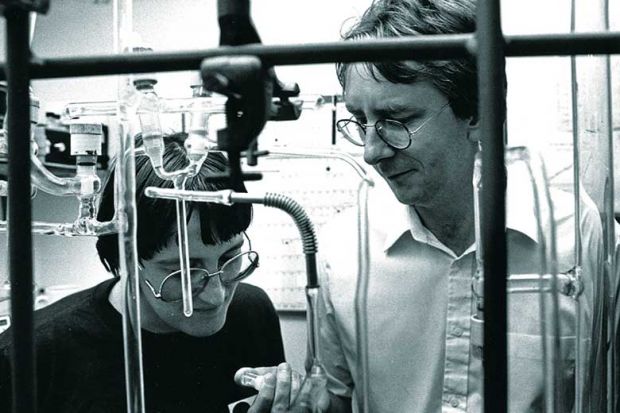

High-quality support for students built on the latest techniques and innovations has been vital to the OU’s success, alongside the standard of its teaching.

Claire Callender, professor of higher education studies at the UCL Institute of Education and Birkbeck, University of London, said the OU’s course delivery was incredibly well thought through. Feedback to students is provided swiftly, which results in strong scores in this area in the UK’s National Student Survey – in contrast to many traditional institutions.

“There are lessons to be learned about replicating the kind of support the OU offers its students. The OU has an army of people and a range of people on hand to provide that support to its students,” Professor Callender said.

Daniel Weinbren, a curriculum manager in the OU’s Faculty of Arts and author of The Open University: A History, believes the institution is likely to remain a leader in distance learning because of its commitment to innovation in pedagogy.

“It is constantly and quickly introducing new ideas about teaching,” Dr Weinbren said. “The booklets it produces, such as ‘how to write a good social science essay’ and other fundamental study skills, sell in huge numbers once they hit the open market…it shows how influential and useful its teaching work is.”

Martin Weller, professor of educational technology at the OU, who joined the institution in 1995, agreed. “People were dismissive of the idea of part-time and distance education, but that changed when people saw the quality of what [the OU] was doing, particularly the printed materials. We found a lot of other universities were using them,” he said.

In recent years, the OU has pioneered the expansion of online education in particular. In 2013, it launched FutureLearn, the UK’s first platform for massive open online courses, hosting programmes from the OU and an array of other universities from around the UK – and now the globe. The OU sold a 50 per cent stake in FutureLearn to Seek, an Australian-based jobs board, earlier this year.

The move of distance learning online has also allowed the OU to lead the way in the development of learning analytics, using data on student achievement and engagement to predict their future performance and to identify learners who need additional support or who may be at risk of dropping out. The scale of the OU’s teaching activities has allowed it to draw insights about which pedagogical approaches are most effective based on datasets of tens of thousands of students.

Professor Weller said that the OU was “quite early in the field because we saw the potential of integrating analytics”.

“It’s difficult to get quick feedback from students in distance learning – in a lecture you can see if they look bored or are talking to each other…but analytics gives us the opportunity to see what students are doing in real time, what they have trouble with and what they are not engaging with,” he said.

While imitation remains the sincerest form of flattery, as the OU turns 50 the risks to its future prosperity are perhaps greater than they have ever been because the entry of more universities into online education erodes its unique selling proposition.

Rebecca Galley, the OU’s director of learning experience and technology, said she had seen a significant increase in recent years in outside interest in what the OU does. “We’ve always believed in sharing our materials and resources; much of the development in our learning platform we share with other organisations,” she said.

“Many of the organisations are snapping at our heels, and we will have to innovate – we’ve been experimenting with more rapid models of productivity – and we have maturity. It’s crucial that we stay ahead of the game, not just for innovation but also for improving the quality of the system and whatever the students need.”

For Professor Weller, the OU has “in some ways been a victim of its own success”. The internet has allowed other universities to jump into distance learning cheaply, whereas in the past the institution had a monopoly. “It’s a more competitive marketplace now,” he said.

However, Professor Weller pointed out that the OU was still set apart from its competitors by its ability to operate at scale. The OU is one of the largest universities in Europe, with 174,898 students.

“People underestimate how difficult it is to do distance learning. We saw that with the introduction of Moocs, and the cost for the support. You need a support structure and to understand its value,” Professor Weller said.

Professor Callender agreed. “Some might want to question whether the OU has lost that lead position, since more universities have become interested in online learning and are providing Moocs and blended learning,” she said. “But it is unclear whether those institutions have learned from the OU and whether those institutions’ motivations for providing distance courses are primarily driven by economic rather than pedagogical reasons.”

In the UK, the growth of online competition has been compounded by the 2012 reforms to student finance, which led to a huge cut in the OU’s block grant and a significant increase in tuition fees. Mature learners have proved unwilling to take on large debts, and student numbers fell by a third between 2009-10 and 2017-18.

The OU – which will welcome a new vice-chancellor, Tim Blackman, in October – is forecasting a £30 million deficit for this year, hot on the heels of a £17.9 million shortfall in 2017-18.

Diana Laurillard, professor of learning with digital technologies at the UCL Institute of Education, said the OU’s role in widening access to higher education in the UK and globally was important, “but there is a sense that it is being left to the OU to tackle those issues”.

“It’s extraordinarily influential. It has educated people who otherwise wouldn’t have learned,” Professor Laurillard said. “It’s a fantastic model, but that doesn’t seem to have been treasured by the leadership in this country.”

There is hope that the forthcoming post-18 review of higher education funding will go some way to tackle the UK’s decline in the number of part-time and mature students, which would be a boost to the university.

“Losing the OU would be a real tragedy,” Professor Laurillard said, especially as workplaces are changing rapidly and employees are at risk of being replaced by automation and artificial intelligence.

“We will need people who can bring creativity, a higher level of critical thinking, and to support them to do more sustainable practices in their work, for example,” Professor Laurillard added. “But that learning will have to be flexible, and that’s what the OU provides.”

后记

Print headline: The pioneer that blazed trail the world would follow