Two volumes titled Vienna 1900 grace my library: one (1989) is subtitled The Architecture of Otto Wagner; the other (1986) concerns Architecture and Design. Then there are massive tomes published to accompany the Paris exhibition Vienne 1880-1938: L’apocalypse joyeuse (1986), and the magisterial show of Wagner’s work in Vienna (2018).

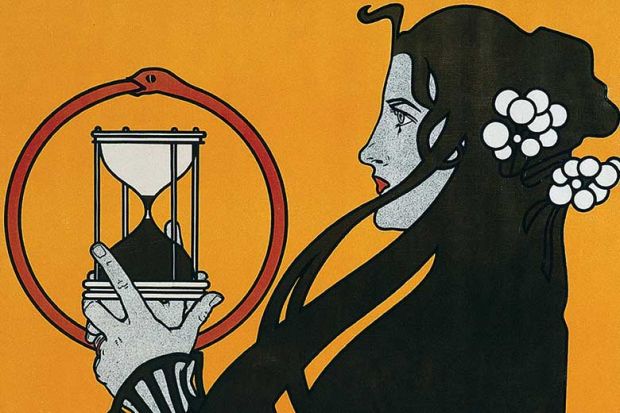

Now, just over a century since the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, we have this wonderful book, encapsulating in its magnificent illustrations what was an extraordinary outpouring of creativity in painting and drawing, the applied and decorative arts, and architecture. It only touches on other aspects, such as music, and so is mainly concerned with visual matters, but what glorious things are pictured within this amazing book, linked to the Arts and Crafts movements, especially in the British Isles, and to the “New Art” of other European countries, called in German-speaking lands Jugendstil! Graphics (especially for posters and book design), furniture, ceramics, metalwork, textiles, glassware and architecture are all given space. One can only regret that Wagner’s magnificent visions for what is today the rather dowdy, incoherent Karlsplatz (despite the looming presence of Fischer von Erlach’s Karlskirche, one of the noblest of all Baroque buildings anywhere) were never realised, and that his superbly inventive (yet anchored in well-tried traditions) designs for the bridges, stations and other fabric of the Stadtbahn (city railway) were so unappreciated with the rise of Modernism that much was destroyed since 1945.

The empire’s last decades produced much of heart-rending beauty, yet not all was joyeuse, for many perceptive writers such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Karl Kraus saw that the apocalypse was not far off. Freudian theories of sexuality embraced childhood too, and “sweet girls” were sought after in an atmosphere where paedophilia lurked (Adolf Loos, the supposed enemy of ornament, was imprisoned for offences against children in 1928, and Peter Altenberg’s collection of photographs of pubescent girls was not that innocent). Sexually transmitted diseases were rife, the hospitals were full of insane victims of syphilis, and suicide was almost fashionable. Arthur Schnitzler’s play Reigen, in 10 “dialogues”, realistically and cynically exposed a series of couplings leading back to one of the first protagonists.

As we should know from what happened in the aftermath of 1914-18, throwing everything out and starting again is not a great idea, either architecturally or politically. I do not think any rational person would now accept that the “successor-states” of Austro-Hungary were roaring, stable successes. And we know what happened to architecture when millennia of experience, knowledge and rich, infinitely adaptable languages were all dumped in favour of nihilism, pidgin-speak and deliberate ugliness. I, for one, abhor that one of the most civilised entities in Europe, producing marvellous architecture, art, music, poetry, opera, literature, artefacts of all kinds, not to mention potable wine and edible food, was replaced with the horrors that led to the totalitarian disasters of National Socialism and repressive Communism.

Vienna 1900 Complete suggests something of what has been lost.

James Stevens Curl’s Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism was published by Oxford University Press in 2018.

Vienna 1900 Complete

By Christian Brandstätter, Daniela Gregori and Rainer Metzger; translated by David H. Wilson

Thames and Hudson, 544pp, £85.00

ISBN 9780500519301

Published 29 November 2018