Ten years ago, the first signs of the financial crisis emerged as banks began to realise that sub-prime mortgage loans were, well, sub-prime. These jitters grew into a global recession.

The most immediate impact was on the financial sector. But higher education was eventually hit too. What have the past 10 years of economic despondency meant for universities’ funding levels, their place in the economy and how they are viewed by policymakers?

As new figures from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development make clear, “higher education wasn't as much affected by the crisis as business was...it continued to steam ahead”, said Dirk Pilat, deputy director of the OECD’s directorate for science, technology and innovation.

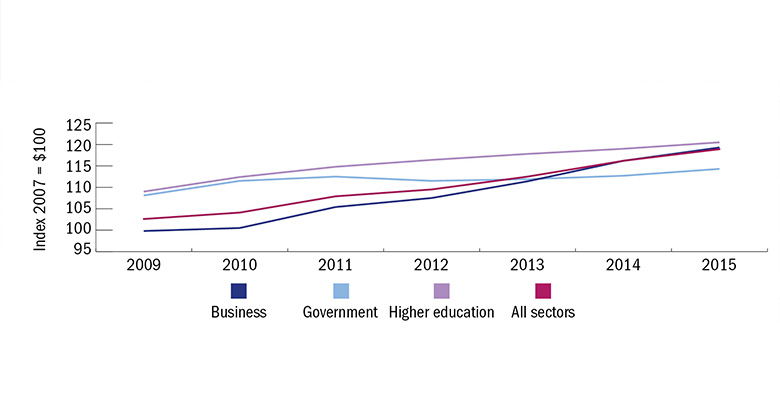

While business investment in research and development, seen as the motor of economic growth, slumped in 2009 and 2010, OECD countries continued to spend more on university-based research.

But the picture is not even. Some countries doubled down on investment, as it was “important to support future growth” and cope with challenges such as ageing and climate change, Dr Pilat said.

South Korea, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Australia and Singapore all increased spending on university research without breaking stride since 2007, according to the data.

Global R&D spending, by sector

Yet spending in the UK has all but flatlined since 2007, as public spending was cut more broadly. The US has also stagnated since 2010.

As recessions left governments scrabbling around for ways to revive growth, policymakers also started to see universities in a different light.

“We have probably seen in many countries that there is bigger pressure on universities to work closely with businesses,” said Dr Pilat, explaining that academics have been asked to devote more attention to commercialising their research. Of their higher education spending, governments have started to ask: “what are we getting out of it?” he said.

In the UK in 2014, for example, researchers were assessed on the “impact” of their work, be it social or economic, as well as its quality. The European Union, through Horizon 2020, its enormous funding programme that began in the same year, has been “very keen” to include small and medium-sized companies as well as academic researchers, pointed out Michael Hopkins, director of research at the University of Sussex’s Science Policy Research Unit.

Search our database for the latest global university jobs

The period following the crash has also seen companies “outsource” their research to universities at an accelerating pace, at least in the UK, said Graeme Reid, professor of science and research policy at University College London, who headed research funding in the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills until 2014.

However, he cautioned against linking this directly to the crash, as it is a trend that has been going on for “a generation” (observers in the US have also witnessed a long-term decline in groundbreaking corporate research, leaving universities to take up the slack).

Still, universities have moved from a “transactional” relationship with companies to “systematic collaboration”, Professor Reid said. For example, drug companies including AstraZeneca have moved into the pharmaceutical research hub around Cambridge to work with university researchers, he pointed out.

As the OECD data show, business investment in research and development has come surging back. Does this mean that the pressure is off universities to drive the economy forward?

Don’t bet on it, said Daniel Ker, an economist at the OECD. The crisis may be over, but governments are hardly swimming in spending money, and so will continue to ask universities tough questions about their economic contribution.

And researchers will be under pressure for the “medium to long term” to solve “wave upon wave” of global challenges, including climate change, renewable energy, drought resistance and so on, added Dr Hopkins: for example, the UK has set up a Global Challenges Research Fund to tackle international threats. “These are all drivers for challenge-led research,” he said, as opposed to projects driven by simple intellectual curiosity.

后记

Print headline: Financial crisis forced universities to justify their economic value