Large workload, time pressure or sense of obligation to their employers and service users – there are many reasons why people work through sickness.

However, the notion that the “ideal worker” shows their commitment by working through illness is being challenged as the true costs of “presenteeism” become known.

Indeed, there is growing evidence that presenteeism is more common than absenteeism and may be considerably more damaging to the productivity of employees and their long-term well-being.

A survey of more than 5,000 academics that I conducted recently with Siobhan Wray, of York St John University, found that almost half of respondents (49 per cent) reported that they worked while sick either often or always. Only one respondent in 10 indicated that they never did so.

When they do report sick, 92 per cent of academics continue to work at home at least occasionally, with more than 20 per cent always doing so.

There are several reasons for this. Those who find their job more demanding, work long hours, perceive less control over what they do or feel less supported by managers are particularly likely to work through bouts of ill health.

Respondents also cited workload and time pressure, linked to the increasingly diverse nature of academic roles, lack of cover for teaching and feelings of guilt about burdening colleagues.

The knowledge that work will keep “piling up” and prompt more stress upon returning to the job was also mentioned.

As one respondent remarked: “One day off sick last year resulted in 150-plus emails, so I have no choice [to take time off]”.

A lack of flexibility in deadlines around teaching and research outcomes and feelings of responsibility to students who would be disadvantaged if the syllabus is not covered or if their work is unmarked were also cited.

Some survey respondents talked about the need to be a positive role model for other staff, especially those with a poor sick record. Others felt the need to “ration” sick days because they suffered chronic health problems, while some kept sick days for unexpected events such as more serious illness or looking after sick family members.

One lecturer said: “I continue to work if I am physically able so I can use my sick leave to look after my elderly mother, who has early stage dementia and will need me in the future.”

Punitive sickness policies and pressure from management, where illness might be viewed as a sign of “underperformance”, job insecurity and temporary contracts also contributed to presenteeism.

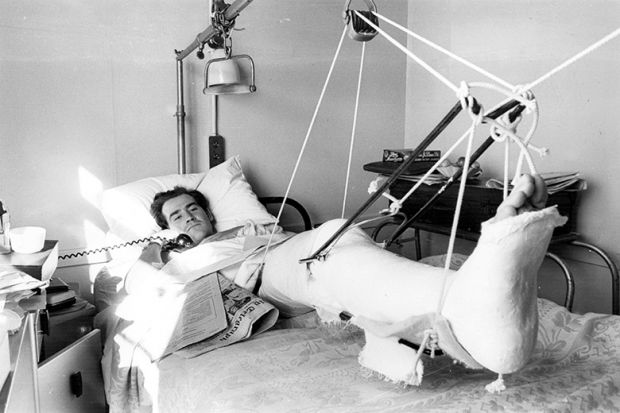

Many academics reported that they continued to work during periods of serious illness or during hospitalisation because of the pressure of work, boredom or habit.

My earlier research found that academics tend to be deeply invested in their work and reluctant to disengage from it. Job involvement appears to be a key driver of presenteeism.

Academics also highlighted self-imposed pressure and the need to meet personal performance standards as reasons for presenteeism. Some disclosed that they missed their work too much to stay away from it: one respondent reported feeling “frustrated and miserable sitting around doing nothing” if they were off sick.

Doing some work when unwell can be beneficial, provided that people feel they have a choice and are able to work within their limits.

Nonetheless, we found that academics who work during bouts of sickness tend to report poorer mental health, less job satisfaction and more conflict between their work and their personal life than those who take time off sick.

These findings, together with those of other studies that have found strong links between presenteeism and job performance and the risks of future long-term sickness, indicate that the risks must be recognised by individuals and organisations.

Although universities will have systems in place to record and manage employee absence, managing presenteeism will be considerably more challenging.

Finding ways to discourage absenteeism without increasing the risk of negative presenteeism will be difficult – especially in a high-pressure, increasingly customer-focused working environment where employees may be reluctant to disengage from their work even when they are seriously ill.

Training is required to help managers notice the signs of presenteeism and develop the sensitivity required to support their staff through periods of sickness.

It is also crucial to raise awareness that an “ideal” employee is not one who struggles to work through illness but rather one who takes enough time off to recover, and that the long-term risks of presenteeism are likely to outweigh any short-term gain.

Gail Kinman is professor of occupational health psychology at the University of Bedfordshire.

后记

Print headline: The working wounded feel chronic pain