The UK government’s new industrial strategy, unveiled by Theresa May during a visit to northwest England on 23 January, is full of proposals that could change how universities and academics work. Although it is so far only a Green Paper that asks for consultation, it makes some stark admissions about the failings of the British economy, and proposes more spending on research as part of the solution.

Organisations such as the Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE) have also repeatedly argued that the UK underspends on research – and it appears that the government now wholeheartedly agrees.

“The UK invests 1.7 per cent of GDP in private and public funds on research and development,” the strategy says. “This is below the OECD [Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development] average of 2.4 per cent and substantially below the leading backers of innovation – countries like South Korea, Israel, Japan, Sweden, Finland and Denmark – which contribute over 3 per cent of their GDP to this area,” it admits.

“What’s really welcome about this strategy is that it’s quite upfront about the issues,” says Richard Jones, a science and innovation policy expert at the University of Sheffield, who has long raised concerns about low levels of science and innovation spending leading to weak British productivity. Low R&D spending has been acknowledged in previous policy documents, he says, but this one comes without any “excuses”. “There’s an air of realism and acknowledgement of the challenges,” he says.

The strategy commits to spending an additional £2 billion a year by 2020-21 (as announced last November), which it says will increase government R&D spending by around 20 per cent. CaSE has calculated that this will boost R&D spending to 2 per cent of GDP, assuming it also stimulates business spending – a large increase, but still short of the OECD average.

One of the key questions now is who gets this money and how it will be spent. Part of the funding – it is not yet clear exactly how much – will be channelled through a new Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund, which will “support business-led collaborations with coordinated research efforts” and focus on the “challenges, opportunities and technologies that have the potential to transform existing industries and create entirely new ones”.

According to Paul Nightingale, deputy director of the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex, this suggests a shift in the way the UK commercialises its research. Rather than funding basic science and hoping the resultant discoveries will be turned into new products and technologies – a “failed model”, says Nightingale – the new strategy will instead ask industry for its “intractable” problems and call on academic scientists to help out. It is a vision of “questions from industry driving research”, he explains.

This “challenge” model of innovation is far from new, and is explicitly modelled on the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in the US (a recent Darpa challenge, for example, asked researchers to build robots that could drive cars, climb ladders and fix leaking pipes).

But it is the first time the UK will have put serious money behind it, says Andy Westwood, an expert in politics and policy based at the universities of Wolverhampton and Manchester. “Whether it overturns the existing model is an interesting question,” he says.

Although the strategy calls for further suggestions, it already has firm ideas on where the new money could be spent: clean energy and storage; robotics and artificial intelligence; satellite and space technologies; healthcare and medicine; manufacturing processes and “materials of the future”; bioscience and biotechnology; quantum technologies; and digital technology such as supercomputing and 5G mobile networks.

Quite a few of these areas are familiar from the “Eight Great Technologies” championed by Lord Willetts, the former universities and science minister. This is important, as “continuity matters in industrial strategy almost as much as money”, says Westwood.

Some researchers may feel left out, as there is no mention of the humanities or social sciences. But Westwood points out that new money for industrial challenges could “take some pressure off” when other researchers compete for other pots of money.

Another question raised by the strategy is how much the government will use research funding to try to spread wealth out of the much richer London and southeast England. It is littered with references to the UK’s geographical inequality, and pointedly notes that “46 per cent of Research Council and Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) funding is spent in Oxford, Cambridge and London”. It suggests creating “new funding streams to support world-class clusters of research and innovation in all parts of the UK”.

But the current system funds research irrespective of place, so the issue of whether to actively spread it out beyond the “golden triangle” of Oxford, Cambridge and London is still the “gorilla in the room”, says Nightingale. To deliberately dish out money to poorer regions would be a “fundamental challenge” to the long-standing Haldane principle of ministerial non-interference in decisions about how research funding is distributed, he thinks.

Is technical education really a threat to universities?

The industrial strategy also focuses on improving the UK’s “technical education”, proposing £170 million of capital funding to create “prestigious” Institutes of Technology.

They are being sold as a direct challenge to universities. The new plans would provide a “credible alternative to the academic route”, claims the strategy’s accompanying press release. The Daily Mail quoted an unnamed government source, who went even further, saying that it was “unwise to force less academic pupils into the straitjacket of university, leaving them drowning in debt for the sake of a poor degree”.

So will a new German-style parallel system of technical education start sucking students away from universities any time soon?

Andy Westwood, an expert of politics and policy based at the universities of Wolverhampton and Manchester, says that this aspect of the strategy was “overspun” when released, as he thinks universities will be heavily involved in technical education regardless.

“It’s more a case that people will be able to do degrees in different settings”, such as workplace apprenticeships, he says. “In that sense it might be competition for the three-year full-time offer, but universities know they can offer a range of things.”

There are also concerns that the money promised will be too small to make much difference.

“The funding proposed is not enough to establish new providers,” argues Chris Jones, chief executive of the City & Guilds Group, which offers vocational qualifications. Care is needed to make sure the Institutes of Technology “don’t simply end up being a rebrand of colleges”, he says.

Martin Doel, former head of the Association of Colleges and professor of leadership in further education and skills at University College London, cautions that universities hoping to participate in the strategy need to be aware that the proposed new technical education system will not be “business as usual”.

The sub-degree education envisaged by the strategy is “not the natural domain of most universities”, nor is the “focus on directly meeting the needs of employers”, he says. Instead, if they want to play a part, universities will most likely have to work with local colleges, he adds.

Fundamental v applied science

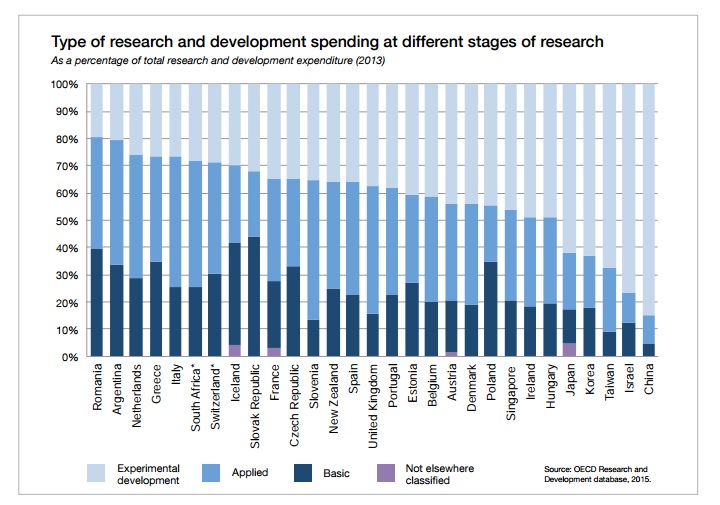

This graph, included in the industrial strategy, is used to illustrate the point that the UK devotes a far lower proportion of its research expenditure towards closer-to-market experimental development than some other countries, particularly in Asia.

“While the way we distribute funding across different stages of R&D is not out of line with other European countries,” it says, “it is striking that in leading innovation nations, such as Israel and countries in Asia, a greater proportion of total R&D investment is on later-stage, experimental development.” China’s share is twice that of the UK, it points out.

This might explain why the UK has “so often pioneered discovery but not realised the commercial benefits”, such as in medical imaging and biotechnologies, it says. The strategy does not suggest reducing basic research funding, but makes clear that new government R&D spending will be focused on industrial challenges.