As is well known, liberal arts institutions (and indeed the notion of the liberal arts itself) are under pressure from many quarters. Politicians, funders and parents fear that the model of more general – rather than vocational – training may be both inadequate and too expensive for the economic conditions of slow growth, wage stagnation and underemployment that many advanced economies face.

While such fears are real, and are particularly exacerbated in the US where the debt that many students and their families take on to finance university education is high, there is something of a disconnect between the view of the liberal arts’ irrelevance and the needs of the modern economy. Few actually contend that vocational education alone is in the best interest of growth and competitiveness.

University leaders are fond of saying that the job of higher education today is to prepare students for jobs that have not yet been invented while business leaders assert that besides specific vocational skills, they are at least as interested in general competencies such as finding and integrating information, communication capabilities, ethical decision-making, or being able to function as part of a team.

Such claims sound like a ringing endorsement for the liberal arts model; that they do not translate into a widespread embrace is not lost on many within the academy.

The disconnect appears to be less that liberal arts training is misaligned with societies’ current and future needs than that graduates in the real world are not always capable of delivering the skills and competencies that the liberal arts are supposed to help develop.

Many are asking the question that was so well phrased by Diana Chapman Walsh and Lee Cuba in a 2009 paper: how might "a liberal education…best produce people who will become 'effective' actors in a complex world?" One fruitful response from educators to this has been to focus on experiential learning as a way to bridge the classroom perspective with applications in the field or the real world.

Numerous institutions are undertaking programmes and experiments to do this: asking students to solve actual problems as part of coursework; internships; shadow opportunities; or providing students with formal reflection practices to contextualise in and out of classroom learning.

At Yale-NUS College, the undergraduate liberal arts institution jointly founded in Singapore by Yale University and the National University of Singapore, our curriculum promotes inquiry from multiple perspectives and incorporates experiential learning from early in the undergraduate trajectory.

Our Week 7 programme, for example, takes place in the seventh week of the first semester of the first year – a time when all freshers are enrolled in the same common curriculum courses. During Week 7, all first-year students participate in a faculty-generated initiative that brings student learning out into the world and connects to both faculty interests and themes of the common curriculum.

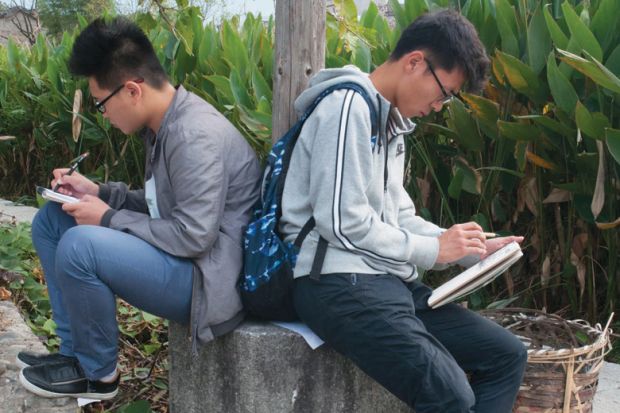

One project called "History, Agriculture and the Future of China’s Villages" took students and an urban studies faculty member to Huizhou, an underdeveloped, rural region in the Pearl River Delta, where they explored ideas for sustainable development in agriculture and tourism. This was run as a charrette, the collaborative and dialogic group work that architects and designers use to solve design problems.

Their experiences, as well as those of the other members of their cohort on different Week 7 projects, were brought back to the classroom to nurture the discussion with real-world examples in the second half of the semester.

Administratively, Week 7 requires a commitment by the whole institution. In addition to committing the financial and staffing resources to support the activities, the college had to recognise and reward faculty who participate. We do this by considering leading a Week 7 project as part of the teaching load, rather than service.

PhD training programmes typically devote scant attention to implementing experiential learning, so our faculty-led Centre for Teaching and Learning runs workshops on this, geared towards Week 7 where faculty learn from each other. Our Writing Centre also supports the programme by suggesting specific writing prompts faculty can use during the course of the week to encourage a reflective practice by students.

Advisers from the Centre for International and Professional Experience follow up with all students to help them think about deepening their Week 7 reflections and outcomes and linking them to future opportunities such as internships, summer study or an exchange programme.

Liberal arts institutions are aware of the challenges that they face today in preparing graduates who will thrive as individuals, citizens and professionals. Experiential learning is one way to help connect the student experience to life after graduation and each institution will find the programmes best suited to its specific students and circumstances.

Our experience suggests that by embedding such programmes into the lifeblood of the institution, the benefits are multiplied.

Trisha Craig is dean for international and professional experience at Yale-NUS College, Singapore.

Write for us

If you are interested in blogging for us, please email chris.parr@tesglobal.com