Breakthroughs in basic science have failed to translate into better care for patients because medical scientists are insufficiently trained to do “bedside” research, three academics from the University of Oxford have warned.

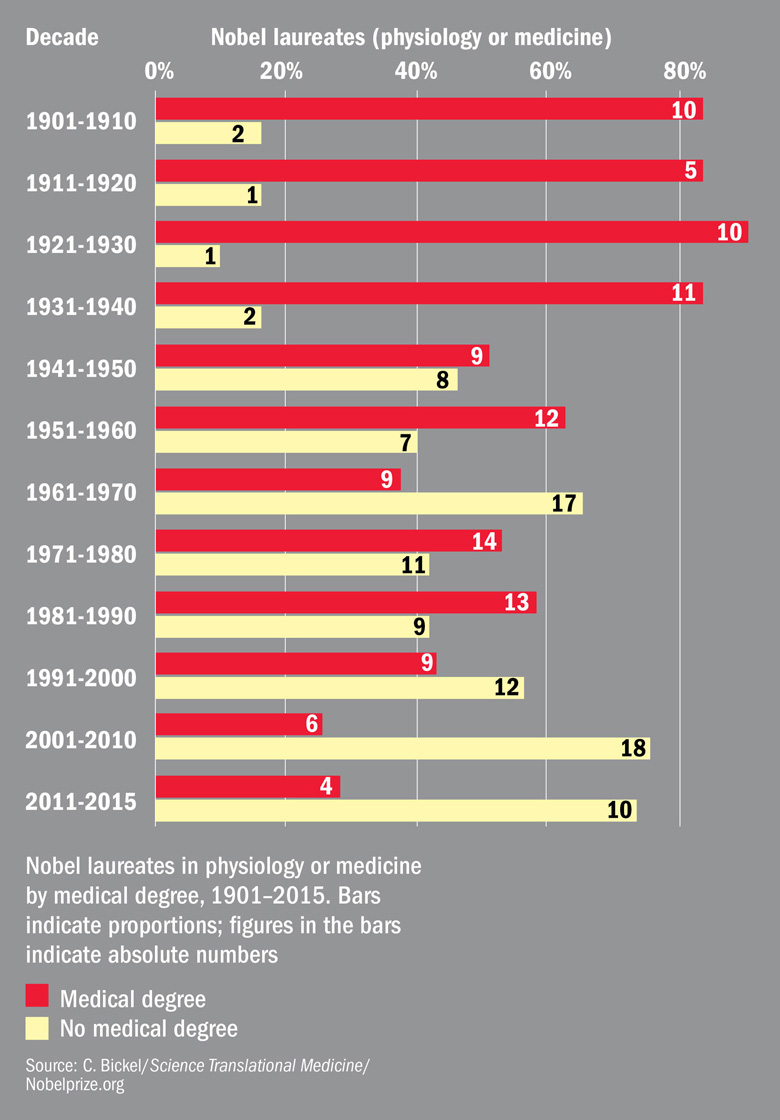

They have calculated that since the beginning of the 20th century a dwindling number of Nobel prizewinners for physiology or medicine have actually held medical degrees.

From 1901 to 1960, what they call "clinician-scientists" won 73 per cent of Nobel prizes. But since then, this proportion has dropped to 43 per cent, and to less than 30 per cent since the turn of the century.

Alastair Buchan, head of Oxford’s medical sciences division, said that over the past 50 years, medical research had undergone two major revolutions: a “mathematical revolution” that examined the impact of lifestyle factors such as smoking on the incidence of disease in a population; and a surge of interest in basic cell biology.

But these two strands of medical research “don’t talk to each other very well”, he said, and the focus on these two new areas had led to a neglect of physiology – of how entire living systems go wrong.

“The problem is that it’s very difficult to get funding over the past 30 years to understand what happens to an organ system,” he said. “The funding agencies have been seduced by the new science.”

In universities, population health departments have received big investments, while physiology, anatomy and pharmacology departments had withered, he claimed.

These shifts in medical research mean that “basic science discoveries have yet to be translated into therapies and improved patient care”, according to “Personalized medical education: Reappraising clinician-scientist training”, published in Science Translational Medicine.

The paper, on which Professor Buchan is a co-author, makes the case for the resurgence of “clinically qualified physicians substantially engaged in scientific research”.

Joint MD-PhD programmes are rare in the UK and continental Europe, the paper says. They are more common in the US and Canada but can be long and financially draining, leading to a 27 per cent dropout rate in the US.

A lack of time during training meant that medical students often ended up being “passive observers” of new science, the paper argues, a problem made worse by a migration of research facilities out of hospitals and into dedicated research centres.

But “research at the bedside” was crucial for understanding the mechanisms by which the body changed, Professor Buchan said. Randomised controlled trials could not help scientists understand why the body functions in a certain way, he said, but observational studies could.

Asked whether ramping up hospital research would cost more, Professor Buchan said that there was “no evidence that doing more clinical trial work costs more money”.

Is there a doctor in the house?: declining number of laureates hold MD

后记

Print headline: Bring medical research back to ‘bedside’, say trio