It is a week until my viva. At this stage, most PhD students will feel a mixture of anxiety and excitement. But instead my feelings are tinged with great sadness, because for the past four years my history supervisor has been Professor David Cesarani.

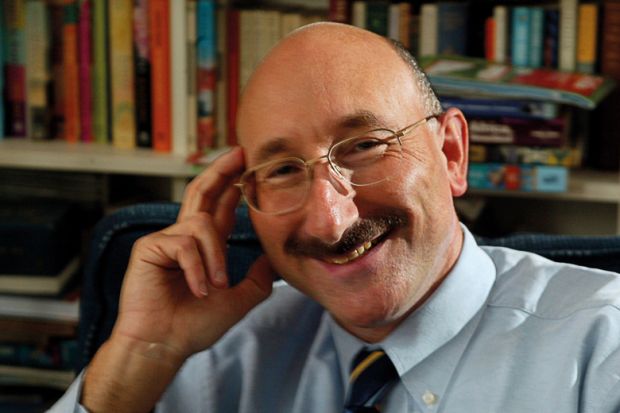

The press has been full of obituaries and tributes to David, giving all sorts of details of his life and work, much of which I hadn’t known. But those of us who were his students knew a David Cesarani not necessarily captured in those media reports.

David called himself an “old-fashioned” supervisor, partly to ensure that students would not expect spoon-feeding, and partly because he didn’t want to have to conform to the methods suggested in the “how to deal with your supervisor” courses that are now mandatory for doctoral candidates. Yet, whatever he termed himself, he was dedicated to his students and gathered us together as an enlarged family. He opened up his home, introducing us with great pride to his family, giving us parties at Hanukkah in the winter and in the garden each summer. David did not compartmentalise, so he managed to include in the supervisory relationship the roles of advocate, supporter, adviser and challenger, as well as host, comic and friend.

He gave his support to me with great warmth, as when he and his wife Dawn came to one of my Cockney-Yiddish music hall shows. At the end he stood there beaming at me, and turning to the group he was talking to, said with a twinkle, “She’s my student.”

I have a long professional career behind me, and have been involved in many sections of the London Jewish community. So I began my PhD studies later than most. With a mere five years between the two of us in age, the supervisor relationship was less paternal than is usually the case. Instead, there were elements of David and I being something more akin to colleagues in a wider professional sense, and being a part of the same broad Jewish community.

When I first thought of doing a PhD, I discussed it with friends, academic and not, and everyone had a reaction. Many loved the idea of me choosing David as a supervisor, from those who had worked with him at the Wiener Library, to readers of his books, to his friends from the New North London Synagogue. Some raised their eyebrows at me for contemplating working with someone whom they saw as having left the radical Left and espousing political opinions they disagreed with. Some had negative feelings about their connection with David, his approach to academia, or his combative rhetoric.

So throughout my four years of PhD research, friends would ask me, with a slight smile on their face, how it was going with David. I particularly enjoyed telling those who expected to hear something different that he was a fabulous supervisor who had challenged my writing like no one had done before in my 25 years of being published, at the same time as being supportive and confident in his belief that I could contribute something substantial to Anglo-Jewish academic discourse. We did not choose to discuss politics outside that which arose from the research.

Part and parcel of David’s determination not to spoon-feed was that he would leave supervision times open to when you, the student, wanted them. Consequently, there were sometimes long gaps between sessions. But when we met, often in his home, he was unstintingly generous with his time. He would not be hurried, and might spend a whole long morning going through chapters or discussing ideas. As any good supervisor would, he challenged, argued and gave generous support in equal measure.

The last time I saw David, he knew he had a tumour and needed an operation, but he never told me. I had come to see him with a copy of my thesis, and the form that required his official signature before I submitted it to Royal Holloway. He flicked through it, making positive comments and even finding a stray typo.

As I prepared to leave, we stood at the door chatting and I wondered whether to wait until after the viva to tell him that he was the best supervisor I could ever have hoped for, not only on account of his erudition and vast experience and the meticulous way he scoured my work for content and style, but also because of the way he “got” the feel of the Yiddish texts and was excited about the cultural content. On impulse, I told him then and there. It transpired that I would not have had another opportunity.

Now, four years after I started my PhD, I am a richer person, and hopefully a more elegant writer, who, thanks to David, has a more nuanced understanding of Anglo-Jewish history. I cannot imagine how much I will miss the collegial relationship we were about to develop. But I feel both lucky and delighted that I was able to be his student for the final four years of his life.

He may have been old fashioned, and indeed some of his students never called him anything but Professor Cesarani. Yet some of us, myself among them, were lucky to become friends; friends who teased him and had Friday night dinners at his home along with Dawn, Daniel and Hannah.

Vivi Lachs is a doctoral candidate in history at Royal Holloway, University of London, researching Anglo-Yiddish popular culture.