Start your university on a path to resilient net zero

Practical tips on how institutions can improve their resilience to climate threats while on a path towards net zero emissions, by Rob Wilby and Shona Smith

The case for decarbonising universities has been made, and many have begun their journey towards net zero emissions by 2050. The same cannot be said for progress on adapting to a changing climate even though costs are already accruing from extreme weather events. Many of our institutions have been damaged by storms, floods and heatwaves, or been disrupted by associated power outages, failure of IT systems, loss of water supplies or broken transport links. Such impacts are expected to grow unless significant steps are taken now, according to the UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2022.

So far, decarbonising and adapting have been largely viewed as separate tasks by universities. Sustainability planning may be regarded as a third work stream. Yet, these should be approached as closely aligned activities in order to maximise co-benefits and minimise trade-offs. For example, restoring and expanding green space reduces impacts from floods and heatwaves by providing drainage and shading while also enhancing biodiversity and capturing carbon. Conversely, installing more air conditioning to control heat in offices, halls of residences, and teaching spaces, will add to carbon footprints.

- Building blocks of university-industry partnerships for positive change

- We’ve engaged 250 student volunteers to hold climate emitters to account

- Transformative not transmissive education for sustainability

How then can institutions start to shape integrated plans for decarbonisation, adaptation and sustainability? To answer this question we are providing a series of resources drawing on a briefing paper published by the UK Universities Climate Network (UUCN). The paper was co-authored by us and 17 colleagues from across 13 institutions. Here, in part one of our series, we outline five steps to help universities get started with their journey towards resilient net zero:

1. Take collective ownership for climate and sustainability action

A senior colleague should report directly to the vice-chancellor and the university senate, with a cross-function remit, clear responsibilities and targets. Immediate tasks would be to consult with stakeholders across the university and with neighbouring communities about their views on climate risks and opportunities. All groups within a university should be engaged – professional staff, academics and researchers, students or business partners – when raising awareness of the need to act, forming an initial vision and identifying priorities. Then, a team can be assembled that understands the institutional governance, processes, core activities and services. Delivering a resilient net zero transition will require ownership and participation by the whole community, not just the senior leadership team.

2. Seek opportunities for climate action within institutional processes

Start with an audit of university procedures and regulations to identify entry points and “hooks” for climate action. Possibilities might include the institutional risk register, business continuity plan, crisis management plan, estates strategy, procurement policies, performance monitoring and reporting of weather impacts. By embedding resilience within corporate processes and structures rather than making it the remit of individuals, progress can be made regardless of staff turnover or changes in leadership. This approach also recognises that climate change is just one among many complex risks that must be managed by universities.

3. Pick a framework for evaluating climate risks and planning adaptations

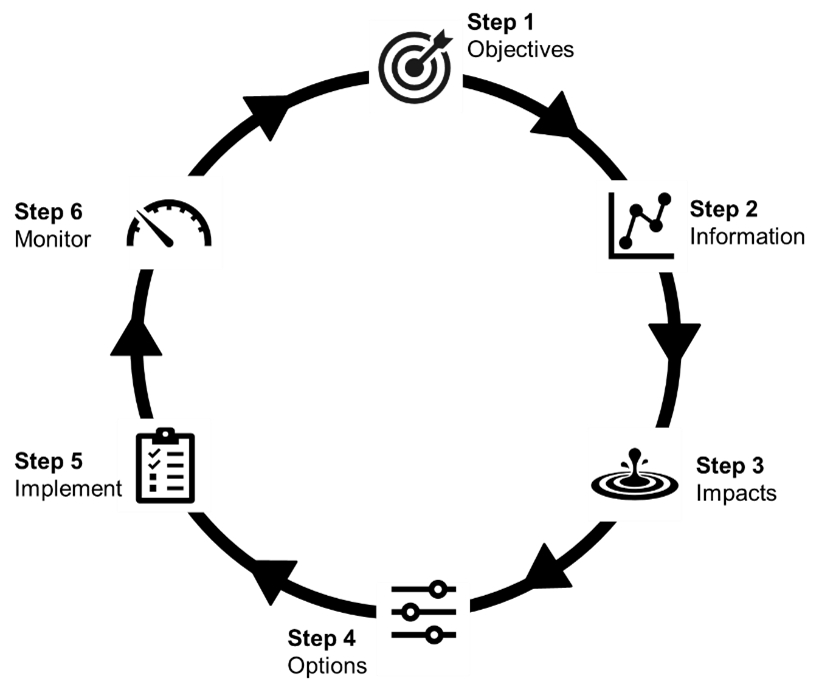

There are many climate risk frameworks to choose from. They are all designed to help managers set goals, evaluate physical climate risks and prioritise actions in systematic ways. As far as we are aware, a bespoke framework has yet to be developed for the higher or further education sector. The UUCN briefing paper refers to a six-step framework (shown below). We will unpack how to use it in the articles that follow this one. Meanwhile, a key point to note now is that climate risk assessment is proactive and an ongoing process. We are seeking to anticipate and prepare, rather than react to extreme weather events and climate change. We must also reassess risks as the institutional context and climate impacts evolve.

4. Recognise and engage institutional expertise and knowledge

Climate risk frameworks are not straightforward to apply. Some universities might decide to outsource this technical work to consultants. But to be effective, inputs will still be needed from teams and specialists across the institution, including: teaching and learning, research centres, finance, facilities management, IT services and other perspectives. Project management teams should draw on colleagues with specialist knowledge in climate policy, information and science. Postdoctoral researchers, interns and undergraduates could be involved in data collection, too. Where there are substantial demands on staff time, this should be acknowledged by formal workloads and incentive structures.

5. Connect with other communities of practice

You can take heart from the fact that you are not alone in navigating the unfamiliar territory of climate risks and resilience building. Although climate action is highly context-specific, much can be gained by sharing and learning from the experiences of others. This “show and tell” approach is taken by the EAUC Managing Climate Risk Community of Practice. Members are invited to show how they have approached a climate-related task, such as undertaking their first high-level campus climate risk assessment. Case studies of actual projects can also showcase the diversity of adaptations in tangible ways. Other resources and examples of good practices have been developed by the Sustainability Exchange.

Next steps

In the next part of this series, we will explain how to define adaptation goals, source key information and involve stakeholders in a university-wide climate risk assessment. Parts three and four will describe, respectively, how to evaluate key risks, then identify and implement adaptation actions to build resilience to climate change. Even if our universities hire consultants to develop plans for resilient net zero, we must still be well-informed and engaged clients.

Rob Wilby is professor of hydroclimatic modelling at Loughborough University, and Shona Smith is research and innovation development manager for the Priestley International Centre for Climate at the University of Leeds.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.