With summer coming, to the northern hemisphere at least, many of those in universities can set aside must-read texts for something more diverting. We asked some of them to choose two books they will read or recommend, stipulating that one be a serious work and the other somewhat lighter. Here are their selections:

Geoffrey Alderman, professor of politics, University of Buckingham

I have long been fascinated by the magnificent Agapemonite church (significantly named “The Abode of Love”) that stands defiantly in the middle of ultra-orthodox Jewish London, hard by Stamford Hill. Founded by one Henry Prince – a Victorian religious lunatic who proclaimed himself the Messiah and earned eternal notoriety after having indulged in public intercourse with one of his many female acquaintances – the movement fell into the hands of a genuine con artist, John Smyth-Piggott, who maintained a commune at the movement’s country retreat in Somerset. Smyth-Piggott’s granddaughter Kate Barlow published an account of life with the Agapemonites, Abode of Love: The Remarkable Tale of Growing Up in a Messianic Cult (Mainstream, 2006), and it is this memoir of one of the strangest Victorian and Edwardian religious cults that I shall be page-turning.

For fun, I shall be reading the brilliant Keith Thomas’ In Pursuit of Civility: Manners and Civilization in Early Modern England (Yale University Press, 2018), and learning from this master of the historian’s craft how it was that urinating in public came to be thought of – at long last – as unfashionable!

Jim Al-Khalili, professor of theoretical physics and public engagement in science, University of Surrey

You may have heard the saying “If you think you’re not baffled by quantum mechanics, then you haven’t understood it.” Well, in the past few years there has been a plethora of popular science books in the area called the foundations of quantum mechanics that explore just what is so puzzling about the most powerful and successful theory in all of science. Philip Ball’s Beyond Weird: Why Everything You Thought You Knew about Quantum Physics Is Different (Bodley Head, 2018) is one of the most lucid and enlightening books on the nature of the reality of the quantum world that I have ever read.

I know that Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens came out a few years ago in hardback, but it is now in paperback (Corgi, 2019), so you have no excuse not to buy it. I guarantee you’ll find it very, very funny. The apocalypse is coming – in fact, the world is about to end next Saturday just before dinner. So an angel and a demon, who rather enjoy their comfortable lives among mortals, decide to join forces to sabotage the End Times. Chaos ensues, of course.

Clementine Beauvais, senior lecturer in English in education, University of York

This summer, I intend to read – at last – a book that’s been on my to-read-for-research pile for months: Merve Emre’s Paraliterary: The Making of Bad Readers in Postwar America (University of Chicago Press, 2017). As a children’s literature scholar and writer, making bad readers is (according to society and most of my friends and family) my daily routine, and I look forward to seeing it theorised. Emre, a young prodigy of anglophone literary and cultural studies, is one of those academics whose style is as inspirational as her ideas.

On the pleasure side – not that research isn’t pleasure, but we perhaps shouldn’t be saying it too loudly – I will be reading enough to keep my Instagram followers happy (a key aim of my existence): children’s literature, comics and contemporary world literature principally. Excitingly, my new subscription to the wonderful publisher Fitzcarraldo has started. I love the concept of subscribing to a publisher. I also have a tights subscription and a contact lenses subscription, but books are even better because they don’t ladder and they rarely give you eye infections. The first book I’ve received is Vivian, a novel about the mysterious photographer Vivian Maier, by the Danish writer Christina Hesselholdt (translated by Paul Russell Garrett).

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor and chief executive, University of Sunderland

Like others interested in modern American history, I am eagerly awaiting the fifth and final volume of Robert A. Caro’s monumental biography of Lyndon B. Johnson. The extent to which Caro and his wife, Ina, have immersed themselves in Johnson’s life is the stuff of legend. For three years, Caro went to live in the Texas hill country where Johnson grew up, partly to research the detail for his books, but also to encourage people to speak to him about his subject. He took a similarly in-depth approach to his book on Robert Moses, the public official who shaped modern New York. Now, Caro has written about his extraordinary approach to the biographer’s craft in Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Bodley Head, 2019). As much as anything, I am looking forward to understanding more about what continues to motivate a man, now aged 83, to devote so much of his own life to the lives of others.

In a different vein, but certainly not a lighter one, I will read Ian Rankin’s latest novel, In a House of Lies (Orion, 2018). I cannot quite make up my mind if Rankin’s wonderfully dissolute detective, John Rebus, is past his sell-by date. Maybe this story will help me decide…

Carrie Tirado Bramen, professor of English and director of the Gender Institute, University at Buffalo, New York

Having just started a book project on the cultural history of the occult in the US, I am curious to read LaShawn Harris’ Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). Harris introduces an intriguing concept called “supernatural labor”, and she features one of New York’s most famous fortune tellers of the early 20th century, Madame Fu Fattam. Her advice accentuated hope to a clientele that struggled with poverty, illness and violence. This underground economy managed to survive in the midst of city-wide campaigns against supernaturalism.

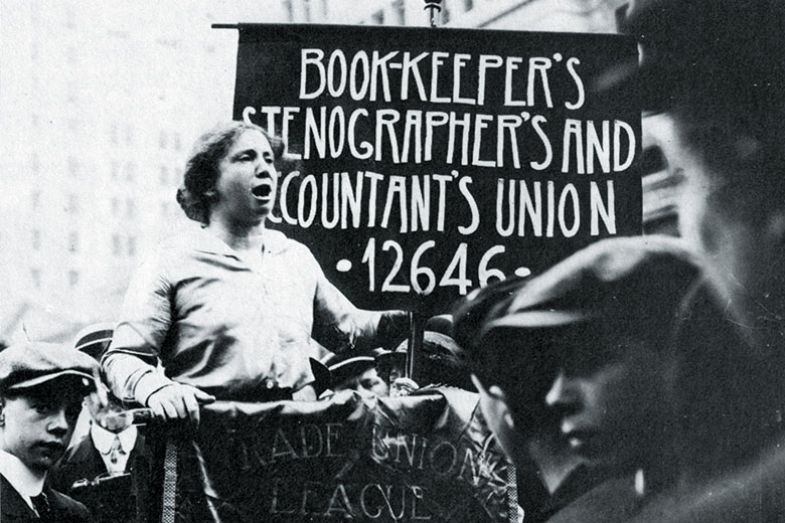

The second book on my list has arrived in time to commemorate the centennial of the 19th Amendment in 2020: Susan Ware’s Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote (Harvard University Press, 2019). Ware tells the story of 19 suffrage activists who have been overlooked in most accounts. This narrative includes Rose Schneiderman, a Jewish immigrant active in union organising who became a women’s suffrage speaker among factory workers in NYC. Ware also includes the African American writer Frances Harper, who addressed a suffrage gathering in 1866 with the words: “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity.”

Clare Brant, professor of 18th-century literature and culture, King’s College London

Depressed about the Anthropocene but don’t know what to do about it? Or where to start? Isabella Tree’s Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm (Picador, 2019) tells the story of how she, her husband and others set about wilding a Sussex estate, featuring what they did and why they did it. What changed is fascinating, inspiring and memorable. The book is also full of eco-thinking: explaining why wilding is different from (and better than) rewilding. The author takes in palaeodendrology questions that cross Europe and make you see trees differently, including what we could and should be planting now.

What a Fish Knows by Jonathan Balcombe (Oneworld, 2016) has a title that sounds like a line by Dr Seuss. Its subtitle, “the inner lives of our underwater cousins”, pushes kinship a bit far – how many removes are we? – but this is a loving and riveting account of fish on their own terms. Compelling on how fish think, feel, perceive, live and die, Balcombe’s deep tour of piscine abilities has more gripping romance in it than most novels. You might even not eat fish again.

Bryan Cheyette, professor of modern literature and culture, University of Reading

I suffer badly from the “scholar’s curse”, as my friends and family often remind me. This means that I do not read for pleasure but, instead, read to write. But I am not sure that this is an either/or situation. My scholarly reading is often pleasurable, if narcissistic, because it feeds my own research. So I am looking forward to Daniel Schwartz’s Ghetto: The History of a Word (Harvard University Press, 2019). It is a comparative book (between Jewish and black history), which is surely the only approach worth taking. Dialogue between communities can be painful, but it is much better than speaking just to a single group.

There are books, however, that can break the scholar’s curse. Kate Clanchy’s Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me (Picador, 2019) is a case in point. It combines poignancy, stunningly evocative prose and the travails and wonders of state school teaching over a lifetime. The resonant voices of her students are immortalised. Clanchy combines learned experience with prose so pleasurable that reading slows so that the book can be savoured properly. It is also an antidote to the research-obsessed scholars who, to their great loss, teach only in the margins.

Sarah Elizabeth Cox, media relations officer and postgraduate history student, Goldsmiths, University of London

In 2011, anxious gender studies graduate and exercise-avoider Heather Bandenburg moved to London for a call centre job. There she stumbled across Lucha Britannia, a group of wrestlers who train and perform in a sweaty club in a Bethnal Green railway arch. She has now crowdfunded and published Unladylike: A Grrrl’s Guide to Wrestling (Unbound, 2019), an inspiring feminist romp chronicling her journey towards becoming global grappler La Rana Venenosa. Wrestlers and wrestling fans have long been stereotyped as jacked-up mullet-wearers with fewer brain cells than fingers, but the modern British independent scene couldn’t be more different, with empowered and empowering women taking the lead.

John Woolf’s 2016 Goldsmiths PhD thesis has been lovingly converted into the enjoyable The Wonders: Lifting the Curtain on the Freak Show, Circus and Victorian Age (Michael O’Mara, 2019), which focuses on P. T. Barnum and “Tom Thumb” while exploring the lives and deaths of lesser-known performers. The author concludes that the voyeuristic Victorian obsession with exploiting those outside the norm, while justifying it under a respectable veneer of “science” or “public interest”, has changed little today.

Kate Devlin, senior lecturer in social and cultural artificial intelligence, King’s College London

Summer is a time when absolutely everyone swears that they’ll catch up on all the things they didn’t get the chance to do during the academic year. Thankfully, the book I have waiting for me is one I’ve wanted to read since it first came out. It’s Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights by Juno Mac and Molly Smith (Verso, 2018). The authors have written a clear, factual and evidence-based account of sex work in the context of labour, feminism and justice – and one that is from the perspective of sex workers themselves.

When work gets pushed to one side (sometimes), then I need escapism. I’m a sucker for a neo-gothic story, so Sarah Perry’s Melmoth (Serpent’s Tail, 2018) is on the list. I love Perry’s wonderful, careful use of language to set gripping and evocative scenes. This reworked tale of a ghostly figure, haunted and haunting, will be just the chill that’s needed when the London temperature hits stifling highs.

John Gilbey teaches in the department of computer science at Aberystwyth University

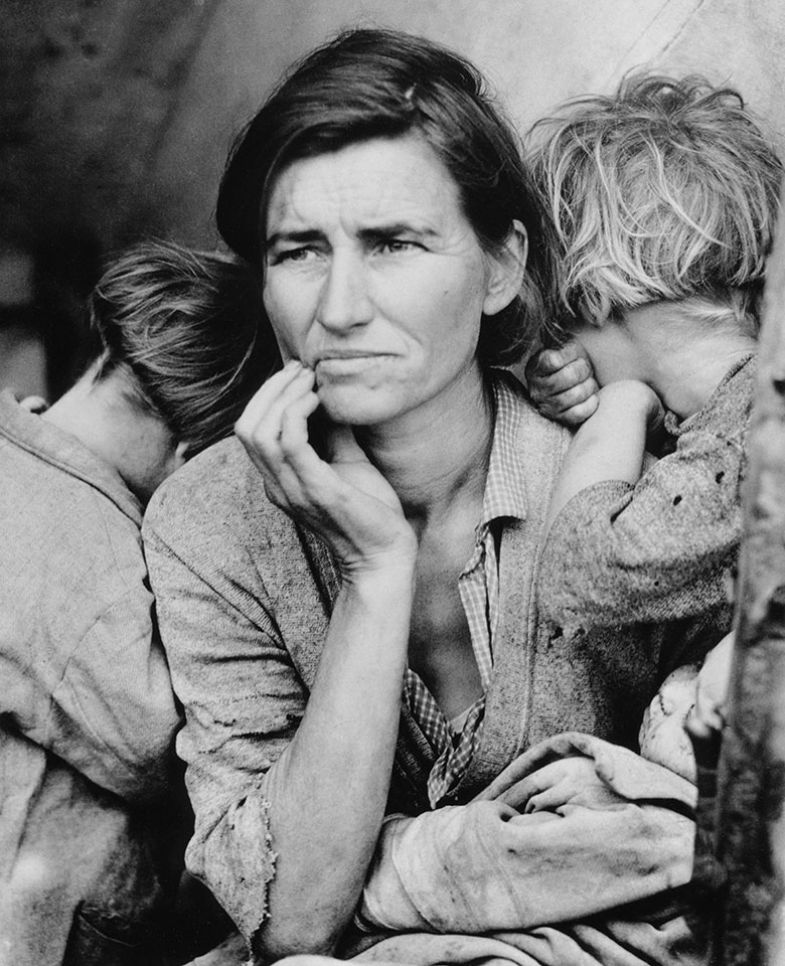

The haunting documentary images captured by Dorothea Lange had a lasting global influence. Her iconic photograph Migrant Mother, taken in March 1936 in Nipoma, California, will for ever be associated with Dust Bowl America – but her work on the plight of Japanese-American internees during the Second World War is equally troubling – and painfully topical. Milton Meltzer’s detailed biography, Dorothea Lange: A Photographer’s Life (Farrar Strauss Giroux, 1978), draws together the many threads of her professional life, including her notable struggles with various federal agencies.

In these times of global upheaval, it takes a special kind of writer to make me laugh about politics – but John Steinbeck manages it with his 1957 satire The Short Reign of Pippin IV: A Fabrication (Penguin Classics, 2001). With French party politics in complete gridlock (sound familiar?), a plot is hatched to re-establish the monarchy. Pippin Heristal, a mild-mannered intellectual descended from Charlemagne, is convinced to become king. While intended as a passive figurehead, he uses the platform to insist on huge social and economic change – resulting in a very short tenure but some intensely amusing set pieces.

Sir John Holman, emeritus professor of chemistry, University of York

If you’re heading for the hills, read Nan Shepherd’s 1977 The Living Mountain (reissued by Canongate in 2011), an outdoor book like no other. The mountain of the title is the Cairngorm plateau, which Shepherd spent a lifetime exploring and which she describes with the intensity of a lover. Her intimacy extends to every feature of the mountain, animate and inanimate, interior and exterior – rocks lead to plants and plants to birds; colour is everywhere. Full of intimate detail, it takes longer to read than you would expect from 100 pages, and the introduction by Robert Macfarlane and the afterword by Jeanette Winterson seem superfluous wrappers for this concentration of lyrical writing, to be savoured slowly.

For a quicker holiday read, it’s time I moved on to Lustrum (Hutchinson, 2009), the second part of Robert Harris’ trilogy on the life of Cicero. Harris’ combination of thorough research with compulsive readability never disappoints me.

Aniko Horvath, research associate on the global higher education engagement research programme, UCL Institute of Education

In academia, when we read for work, we often focus on the sections relevant to the immediate task. With many texts, we never regret having to do so. Occasionally, however, we come across books we want to read from cover to cover. Anthropologist João Biehl’s Vita: Life in a Zone of Social Abandonment (University of California Press, 2013) has been one such book for me. Set in Brazil, in an area of a big city where the “unwanted” – the homeless, the mentally ill, the sick – are left to die, Biehl walks us through the painful stages of people’s lives disintegrating under economic pressures and dependence on pharmaceuticals. He is unforgiving – and addresses us all – when he exposes the role of the public and the state in allowing a consensus to emerge that leaves the “unsound and unproductive” to die abandoned. It is hardly a light summer read, but the dystopia it explored is rapidly catching up with us.

Between the more serious books, and running after a super-fast toddler, I will snatch spare moments for István Örkény’s witty, absurd and ironic One Minute Stories (translated by Judith Sollosy; Corvina, 2013), a true classic of central European humour.

Rivka Isaacson, senior lecturer in chemical biology, King’s College London

This month, I am presenting at the Iris Murdoch Centenary Conference in Oxford. Since the recommended retail price is £75.00 (eek!), I am hoping to pick up a heavily discounted copy of Lucy Bolton’s Contemporary Cinema and the Philosophy of Iris Murdoch (Edinburgh University Press, 2019). I’m a lot better versed in Murdoch’s novels than in her academic philosophy, although I’m anticipating that the conference and this accessible, insightful book will give me my seasonal boost in the latter this summer.

Thanks to a book review I wrote for Times Higher Education, I was recently invited to chair a fascinating session at the York Festival of Ideas on the art of visual imagination. I bought a beautiful pocket-sized book called To See Clearly: Why Ruskin Matters (Quercus, 2019), by one of the panellists, Suzanne Fagence Cooper, research curator for a recent exhibition called Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud (York Art Gallery). I am particularly excited to read this because I work in Borough and attended an inspiring lunchtime event run by Bankside Open Spaces about Red Cross Garden, a social housing/welfare project spearheaded by Octavia Hill with support, financial and otherwise, from Ruskin.

Farah Karim-Cooper, head of higher education and research, Shakespeare’s Globe

This summer, while most people may be seeking some escape from reality, I will be immersed in death and feminism. As my current research is on death in Shakespearean performance, I will be rereading Michael Neill’s Issues of Death: Mortality and Identity in English Renaissance Tragedy (Clarendon Press, 1997). This classic and seminal study explores the iconography of death, in particular the tradition of the danse macabre, the spectre of death as it was encountered in the human anatomy theatres of the age and some of the great tragedies of the period. Neill shows us that at their heart is a harrowing fear of annihilation in Elizabethan and Jacobean culture.

On a (somewhat) lighter note, I plan finally to read Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist (Harper Perennial, 2014). I like it that her collection of personal essays promises to offer an honest perspective on the contradictions inherent in and the conflicts of desire that permeate an individual’s feminism. I am hoping it can perhaps provide some guidelines about navigating the territory of feminism in a world where women’s rights seem to be under threat. Apparently, it’s funny too, so I imagine Gay will provide laughs as well as something to think about.

Joanna Kidman, associate professor of education, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand

Every so often, we sociologists peek over our disciplinary parapet and catch sight of the field of history with its moated castles and rolled lawns. We’re like neighbours who don’t have much in common, but if we meet in the driveway we’ll kick the tyres on our cars and talk about motoring. It’s not a close relationship – except when it is. In He Reo Wāhine: Māori Women’s Voices from the Nineteenth Century (Auckland University Press, 2017), Maori historians Lachy Paterson and Angela Wanhalla scoured 19th-century archives for accounts by Maori women about life in settler-colonial New Zealand. This was a turbulent time in the nation’s history, and the texts of speeches, letters and other documents show how Indigenous women, in their own words, experienced wave after wave of British invasion. This is history at its most incisive, but it is also a gift to sociologists, like me, whose research centres on the aftermath of colonial violence.

For fun, I have a full set of Agatha Christie novels, each of which I treat like a dose of analgesic after long summer afternoons spent in faculty meetings. On those days, I pick titles that reflect my mood: Ordeal by Innocence (Harper Collins, 2018) is a particular favourite.

Reina Lewis, centenary professor of cultural studies, London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London

Shalina Shankar’s Advertising Diversity: Ad Agencies and the Creation of Asian American Consumers (Duke University Press, 2015) will shed light on what happens when usually ignored consumers are wooed by advertisers; specifically, if and how this creates career opportunities for people “from” those communities. Where I examine how religious (and religio-ethnic) dispositions become commodified in the competitive industry infrastructure now developing within the (once small and niche) cross-faith modest fashion market, she focuses on the commodification of racial and ethnic difference.

For relaxation, I shall re-re-reread Georgette Heyer’s Regency romances (a passion I share with a number of my peers). Novels populated by feisty, intelligent heroines never conventionally beautiful, and chased by/chasing handsome heroes, are not a genre I’d seek out – but somehow, with Georgette at the pen, it’s OK. And oh, m’dear, those frocks!

Philip Moriarty, professor of physics, University of Nottingham

Back in December, in THE’s suggested winter reads, I was eagerly awaiting the publication of Angela Saini’s Superior: The Return of Race Science (Fourth Estate, 2019), the follow-up to her compelling and forensically researched Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That’s Rewriting the Story. I was delighted to receive a pre-publication copy and read it almost in one sitting. My single-sentence review? Stop what you’re doing now and go and order Superior instead – I promise you’ll not regret it. It is an exceptionally important examination of the origins and influence of scientific racism, which, given the recent resurgence of “race realism” driven by racist pseudointellectuals and their online enablers, is also about as timely as any book could be. A gripping read.

For a rather more light-hearted tome, I’m tempted to suggest Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos, a laugh-out-loud, pitch-perfect parody of the worst excesses of vacuous, preening self-help guff. It’s still topping best-seller lists (although I’ve got to admit that I sometimes wonder if quite everyone is in on the joke). I’m instead going to enthusiastically recommend the wonderful Soonish, by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith (Particular Books, 2017), whose subtitle tells you all you need to know: “Ten Emerging Technologies That’ll Improve and/or Ruin Everything”.

Tamson Pietsch, senior lecturer in social and political sciences and director of the Australian Centre for Public History, University of Technology Sydney

Everyone should read Bruno Latour’s Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime (Polity, 2018). I’ve sent it to people in the mail, forced copies on friends for their birthdays and talked endlessly about it at social events. It’s jargon-free and it’s short, and it is the book that, more than anything else I’ve come across, helps to make sense of the entangled politics of ecological destruction, inequality, deregulation and globalisation. Not only does it offer a startling new analysis, it also points to an alternative: learning new ways to inhabit the earth is our biggest challenge. We need to live together in our common home.

I am looking forward to reading Sumner Locke Elliott’s recently reissued 1963 classic, Careful, He Might Hear You (Text, 2013), which was given to me by a friend, insisting that it was high time I read more mid-century Australian fiction. The back cover tells me it’s an aunt book, in which snobby Aunt Vanessa returns from London to Depression-era Sydney to whisk away her six-year-old orphaned nephew who has been living with his other Aunt Lila. Drama, together with the complexities of family life between the wars, ensues.

A. W. Purdue, visiting reader, the Open University

The echoes of the war years and the traumatic ending of France’s long hold on Algeria resound in Sebastian Faulks’ magnificent novel Paris Echo (Hutchinson, 2018). The two leading characters are very different. Tariq, a young Algerian whose deceased mother was half-French, has set off for Paris in search of his dream world of available girls, but also, unconsciously, to trace his mother’s early life. Hannah, an American in her thirties, is a postdoctoral researcher whose subject is Paris during the German occupation. Almost surreal at times, this is a haunting novel in which the echoes sometimes appear more like ghosts. Even the metro system, which joins yet divides the fragmented city, reveals memories of an uneasy mid-20th century past.

In contrast, Anne de Courcy’s Chanel’s Riviera: Life, Love and the Struggle for Survival on the Côte d’Azur, 1930-1944 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2019) gives us delicious gossip. France’s leading designer was the epitome of chic. When she acquired a magnificent villa on the Côte d’Azur, the rich and famous – among them Jean Cocteau, H. G. Wells, Salvador Dalí (and, after the abdication, the Windsors) – followed. They created a gilded and hedonistic world, which continued until the fall of France in 1940.

Jennifer Schnellmann, associate professor of pharmacology, University of Arizona

Biologist Nathan H. Lents’ Human Errors: A Panorama of Our Glitches, From Pointless Bones to Broken Genes (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2018) explores every physiological inconsistency we humans have, from junk DNA to the atrocious architecture of our sinuses. I expect to borrow from Lents’ highly lucid explanations of how we create horrendous environments for our imperfect selves, allowing overindulgence (obesity, diabetes) and even death (faulty logic, unsafe practices). This rich material will augment the physiology I feature in my pharmacology lectures and balance the perpetual message of medicine, that we are perfect and miraculous creatures. Most likely, our biological shortcomings are far more interesting.

Humourist David Sedaris’ Calypso (Little, Brown, 2018) will be an indulgent treat of 21 autobiographical essays. A long-time fan of this author, I anticipate reading deeply thoughtful prose describing his eccentric and colourful family and his perfectly poised partner, Hugh. I also expect to bray like a wheezy donkey at his scatological, X-rated humour and the wildly inappropriate questions he lobs at unsuspecting guests during his multi-hour book signings.

Jeremy Till, pro vice-chancellor, research, and head of Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

I am climbing into a deep, dark, hole of reading about the climate emergency, with various books competing with each other to present the most apocalyptic vision. I think Clive Hamilton’s Defiant Earth: The Fate of Humans in the Anthropocene (Polity, 2017) is going to win – a necessary and urgent wake-up call. I know some say that getting too absorbed by the bad news is paralysing in terms of taking action, but as a designer I need to know the context to work out of.

After this, I am going to need something to cheer me. I am late to the party, but Chris Kraus’ I Love Dick (Serpent’s Tail, 2016) sounds like it will fit the bill: a confessional rampage through the cultural scene, apparently with a black-humoured excoriation of the art world and its accompanying rituals. And in a month in which a Lincolnshire primary school sees fit to send its girls to domestic studies and boys to technology studies, it is clear that we need more than ever Kraus’ subversive spiking of the patriarchy.

David Wheeler, editor at Al-Fanar Media

I can recommend Ben Rawlence’s City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp (Macmillan, 2017) as one of the few non-fiction books – maybe the only one – that provides serious insights into the layers of corruption, suffering and chaos that can reign when refugees are herded into one artificial city. Rawlence visited Dadaab, with about 300,000 residents, over a period of four years. Here, Kenyans were the usually unwilling hosts of Somalians pushed out of their country by al-Shabab militants. The Kenyans’ desire to send the Somalians home is mirrored in attitudes towards Syrians in Jordan and Lebanon today.

For a book that is probably not most people’s idea of beach reading but does have a compelling narrative, I can suggest Dave Eggers’ What Is the What (Penguin, 2008), which tracks the tale of a “lost boy” of South Sudan who fled to Ethiopia, then Kenya, and wound up in America. In a fictionalised true story, the urge of the protagonist, Valentino Achak Deng, to seek out education is as strong as hunger or thirst. There are lessons for those seeking to help 2019’s generation of young refugees.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login