Is there really a connection between philosophy and sex? I mean an interesting one. There has been a tendency in recent times for “philosophy of” books to proliferate – though here it’s literally philosophy and. Philosophy of film, philosophy of sport, philosophy of walking: the list goes on.

One might say, alternatively, that few things are less subjected to useful philosophical analysis than sex. Indeed, it is precisely the abandonment (turning off?) of cognitive ruminations that is part of the attraction of sex: letting oneself go viscerally. If you are abstractly turning what you are doing over in your mind, then you’re rather missing the point. Just as if a partner or offspring asks you if you love them, they don’t want you to step back and say: “Hang on a minute, let me consider the arguments for that.” But, of course, in riposte, one might say that even weighing the relevance of philosophy to sex is itself “doing philosophy”, so there’s no escape.

The outset of the book is a little reminiscence of Damon Young’s libidinal, but not yet erotic – let alone romantic – schoolboy awakenings, perceptively noting how one is as if seized by an external force and made to look, in this case at the legs of a female classmate. We then get a brisk, not to say hectic, tour of what philosophers, and a lot of other people, have said about sex. In a sense, it’s erudite; on the other hand, you might think: boy, does he range about a lot!

On the general place of sex in a life, philosophers tend to fall into three classes: those who think it a massive distraction from thinking; those who think it’s an eye-opener into a deeper view of the world; and those who think it’s utterly neutral and has nothing to do with philosophy at all. I’d say all could be true simultaneously, dominant at different times or on different occasions or more or less true for different people. But Young’s peregrinations have a slightly different motivation: not so much the placing of sex in life, more that thinking about sex is itself fun, just as sex is.

David Hume doesn’t say much about sex, but he’s spot on, pointing out how the intellectual and the pleasurable, the rational and the non-rational (not thereby irrational), while they are abstractly distinct, are in reality inextricably intermingled. In what we think and believe, we are not as rational as we like to think we are. This is not to undermine there being clearly such a thing as good and bad reasoning, just as there are facts and non-facts. But we kid ourselves if we hold ourselves to be above the non-rational in determining our beliefs. Indeed, we’ll tend to drop our guard against being determined by the non-rational when we shouldn’t be if we think that. Sex offers us an excellent example of how something non-rational can just put us somewhere in our thoughts and feelings without any rational process going on at all or frankly even being relevant.

Let us take a couple of the propositions in the book. Before that, I should give notice to the delicate reader that the language in it is robust and explicit, and if you don’t enjoy that, you won’t enjoy the book. It didn’t bother me in the slightest. It covers every nook, cranny and trope of sex between people and with yourself.

So, sex is fun and writing about sex is fun. Is it? At this length? Young pulls in everything you can think of about sex in a kind of mad compendium. Reading the book might for some people feel like being trapped in a corner by a verbal sex maniac. As for sex, by the time you get to the end, you might well have gone right off the idea. You’ll be telling yourself: I didn’t realise it involved all this! I thought I was just having a good fuck. There are perceptive insights along the way, and Young has a knack for articulating thoughts about sex you only ever had inchoately. So my advice about reading this book is that it’s best dipped into.

Another thought in the book is: sex is a moral matter. Young claims this is so because it follows from sex involving other people. In fact, the sex he covers in the book does not always involve other people, not unless the virtual count. But in any case the justification is too broad and would make every interaction with others a moral matter, thus rendering it an empty truism that sex is a moral matter. Sleep and food often involve others, but that does not by itself make them moral matters. I’d say that sex itself is morally neutral. Lots of people, most notably the religious, have been only too enthusiastic about making sex otherwise. There are lots of practical reasons for that, some understandable, some not. But sticking to acts of sex with others, I think Young confuses acts of sex with the psychological and practical consequences, though these are not peculiar to sexual relations. Sex might lead you to misunderstand and exaggerate the true worth the other person places on you, and so into foolish declarations of love and devotion that are unwanted. But that kind of misunderstanding can arise in other ways. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with promiscuity, though you might wonder whether you can cope with it psychologically. The moral questions start when you step back from the sex itself and ask yourself if you are hurting someone’s feelings or deceiving them.

It’s not the sex itself but what follows from it that may, but may not, put it into the moral domain. Indeed, part of what is wonderful about sex is that it isn’t a moral matter. One may claim that there is no relevant moral reason not to have sex with another consenting adult if you’ll both enjoy it and there are no extraneous consequences that need to be considered as ethically right or wrong.

I’m guessing Young might say this is a simplistic view of sex, though one might also say it’s just simpler. You either enjoy it or you don’t. If you do, do it and if you don’t, don’t do it – always with the proviso that proper mutual consent has taken place, and thought given to whatever consequences might follow. As such, and in addition, it’s no one else’s business. Sex is a fact, one of the facts of life, as they say, and I think overlaying it with a deluge of semantic and normative meanings risks sucking the life out of it.

Of course, there are putatively “darker” sides to acts of sex, kinks and bendings and games, but again it’s not clear that they are darker in any moral sense, or are just how you, and whoever you are with, like it. Young seems to be sympathetic to the idea of sex as funny and creepy – I can’t say I find it remotely either. Sex is like humour: writing about it is nothing like as much fun as doing it. Scrutiny evaporates it.

One should acknowledge, though, one aspect of sex that the book seems to underestimate: the vital place of intimacy, and moreover that to have sex with someone is a great privilege – it’s certainly not a right – and an enormous act of trust. This is essentially a psychological and aesthetic matter, not a moral one. To share with someone something bodily sexual is to fundamentally drop your guard. This is what makes it exciting, astonishing and wonderful.

Not much further to say about sex after this book. Back to sex itself, then!

John Shand is honorary associate in philosophy at the Open University.

On Getting Off: Sex and Philosophy

By Damon Young

Scribe, 288pp, £12.99

ISBN 9781912854233

Published 11 February 2021

The author

Damon Young, an honorary fellow in philosophy at the University of Melbourne, was born in suburban Melbourne and raised on the Mornington Peninsula nearby. Behind the family’s “blue-carpeted, orange brick house,” he recalls, “was a creek that led to the beach. I sometimes hacked my way through blackberries to go spearfishing or crabbing. There was no bookshop in the village, but plenty of books at home (and comics in the newsagent).”

After studying philosophy and literature at Swinburne University of Technology, Young went on to a doctorate where his supervisor put great stress on “wide reading, from psychology and sociology to physics and biology. This wasn’t arrogance, but humility: we had a great deal to learn from other disciplines. I still try to work this way.”

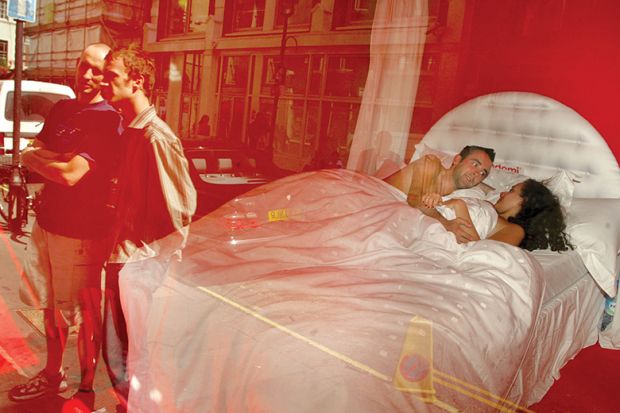

The author of Philosophy in the Garden (2012), How to Think about Exercise (2014) and The Art of Reading (2016), Young says he is “curious about the familiar things we don’t talk about. And I’m especially curious about the familiar things philosophers don’t talk about. Thinkers have often been drawn to lawns or grottoes, yet there is little philosophy about gardens. And thinkers have certainly enjoyed the full gamut of erotic life, yet sex itself has chiefly been trivialised or vilified. I want to think more seriously about sex (even if this means joking).”

Asked about the particular challenges of writing about sex, Young admits that “writing about my own love life has been uncomfortable and unflattering – sometimes upsetting. It’s also been ethically exhausting: trying to do justice to others’ intimate lives.”

“Tone has been vital,” he continues. “On one page, we might find absurd leather phalluses. On the next, brutal chauvinism. I’ve tried to balance levity with solemnity or contempt.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The joy of just thinking about it

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login