Browse the full results of the World University Rankings 2024

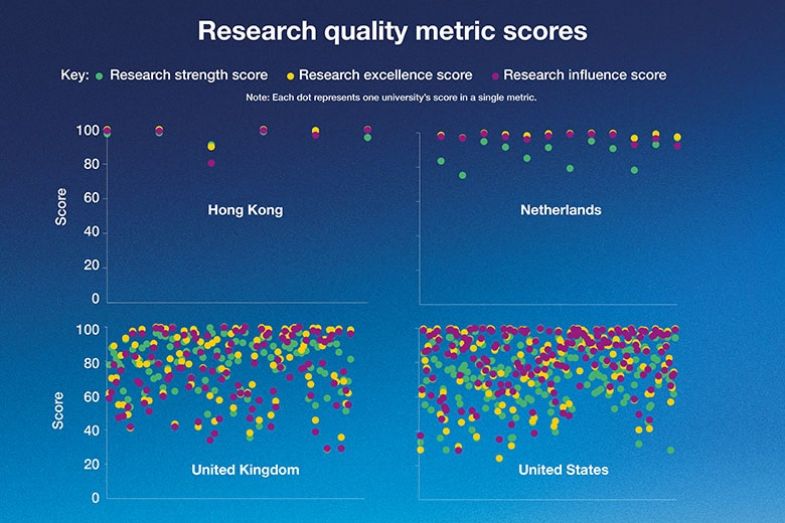

Hong Kong and the Netherlands are the world’s top-performing countries for research quality, according to new Times Higher Education metrics giving fresh insight into the shape of research at universities.

The THE World University Rankings’ newly renamed research quality pillar, which previously only measured the citation impact of universities, includes new metrics to consider not just the number of times a university’s published work is cited by scholars globally, but also the number of publications in the top 10 per cent for field-weighted citation impact worldwide (research excellence). Further, it tracks when research is recognised in turn by the most influential scholars in the world (research influence).

With an average score of 91.6 out of 100 for Hong Kong and 87.4 for the Netherlands, the two countries lead the table for research quality, when countries with six or more institutions are considered. As well as leading the overall pillar, the two countries achieve the highest average scores for the new research excellence and research influence metrics (although the Netherlands is slightly ahead of Hong Kong on these).

World University Rankings 2024: results announced

The new metrics give nuance to the understanding of research quality in these nations, and their top scores signal that they are the strongest players not only in terms of the overall quantity of research citations (which could be a result of a small number of highly-cited papers), but also in terms of the amount of world-leading research and the number of citations from the most influential research papers.

Lili Yang, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty of Education, says that a major reason for Hong Kong and the Netherlands’ high-quality research is that both systems are small but mighty. Hong Kong has eight government-funded universities, six of which are ranked in the World University Rankings 2024 (five of those feature in the top 100). The Netherlands has 12 ranked universities, all of which make the top 250.

Yang says that Hong Kong’s lead in research quality may be traced to “the overwhelming emphasis on each individual researcher’s research performance at Hong Kong universities”.

“Relevant bibliometric data are used by senior managers in keeping track of the universities’ overall research performance and are considered in research performance evaluation,” she says.

Simon Marginson, a professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, says that universities in both Hong Kong and the Netherlands have been “designed” with a system-wide approach to improving research standards. As a result, “there’s a significant group of high-quality research universities, rather than a smaller elite group”, he explains.

“Extreme hierarchy and stratification between institutions is less good for overall system performance,” he says, citing the US as an example.

While the US has leading institutions, it underperforms in research when scores are adjusted for population size. Six of the top 10 universities for research quality are in the US, with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology the nation’s leading performer. But the average score for research quality for the US is 74.4 – much lower than that for Hong Kong, the Netherlands and even larger countries like Australia (which has a score of 84.0).

When looking at metric-level performance, Hong Kong has the top score of 96.6 for research strength, a new metric based on the 75th percentile of field-weighted citation impact, indicating the strength of typical research at an institution. The United Arab Emirates ranks second with 88.4 and the Netherlands follows very closely with 88.0.

In the metric for research excellence or the amount of research in the top 10 per cent worldwide, the Netherlands leads with 98.9, followed by Hong Kong with 98.2 and Finland with 93.0.

The third new metric on research influence is also led by the Netherlands with 97.2, followed by Hong Kong with 96.0 and Denmark with 91.0.

Raymond Poot, associate professor of cell biology at Erasmus University Rotterdam, says that the Netherlands’ strategy since 1991 has been to handpick scientists based on their citations and publications in high-profile journals. He adds that the European Research Council was modelled on the talent competitions at the Dutch Research Council (NWO), attesting to the system’s success.

Poot has also examined research output in relation to the societal benefit or the wider impacts of research, including economic growth, innovation and patents, as well as insights that cannot be patented.

“Both on output numbers and societal benefit, [the Netherlands’] strategy appears to pay off,” he concludes.

“A frequent misunderstanding is that the number of citations and publications in high-profile journals are separate entities from societal benefit. They are not. On the big numbers [of citations] they are two sides of the same coin.”

Salvatore Giusto, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Amsterdam’s department of European studies, says that from a researcher perspective, the Netherlands’ system is good at backing research with funding for open-access publishing. In his eyes, this can offset the pressures faced by researchers in a competitive system.

“This type of support is important because it can counterbalance both the greed of publishers and also the publish-or-perish ideology,” he says. Research that is published open access also has a higher chance of being found, read widely and then cited.

Giusto, who is of Italian origin, believes that the research culture in the Netherlands also benefits from the diversity of scholars at its universities. He says that the Dutch academic space can be like “a bridge between the Anglo-Saxon world and the European continental word” and this spurs research and publishing in a way that is not ethnocentric. This is helped by the fact that the Dutch are “informally bilingual”.

While the Netherlands and Hong Kong lead the new metrics, other nations have seen a boost in their scores at the pillar level now that it provides a more comprehensive assessment of research quality beyond field-weighted citation impact. Among these are Australia, Italy, Slovakia, South Korea, Brazil, South Africa and Canada.

Meanwhile, some countries have seen a dip, signalling that despite having a high overall quantity of citations, they produce less world-leading research and are less influential in the knowledge economy. These include Saudi Arabia, Colombia, Iran and Nigeria. Most European countries have improved in research quality compared with last year, with the UK, Italy and Germany making the highest gains. However, France’s score in this area continues its decline since the 2020 edition of the rankings – although its score remains higher than the world average.

Oxford’s Marginson says that ultimately, for both individual universities and country systems, research performance comes down to “quantity of quality”. The Netherlands and Hong Kong, he says, lead “a small group of very strong, small and middle-sized research countries that outperform everyone else on a unit-by-unit basis”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login