James Herbert believes more university leaders should embrace controversy: “Most of my fellow presidents are running in the opposite direction – they want to avoid controversy at all costs and make these problems go away.”

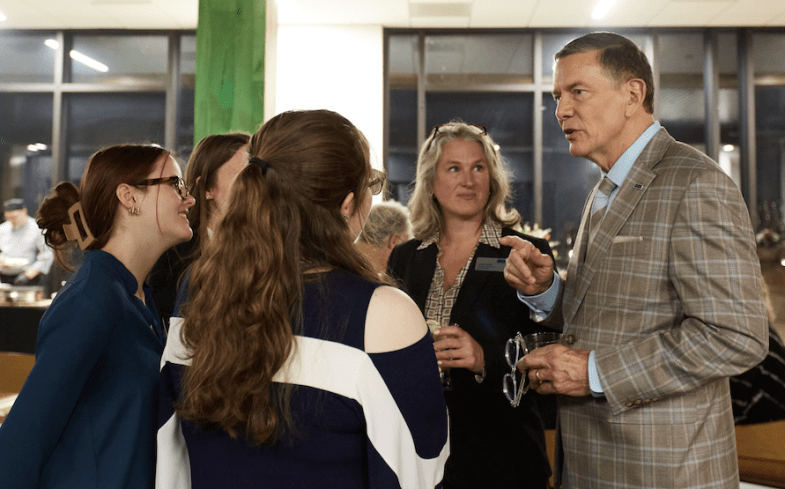

Committed to placing robust yet respectful debate at the heart of learning, the psychologist and president of the University of New England (UNE) tells Times Higher Education how he has fostered an environment on the Maine campus in which views are challenged and students are sometimes made to feel uncomfortable – before demonstrating his readiness to wade into topics you’re told not to discuss in polite company.

Herbert considers universities to be “marketplaces of ideas” and says good ideas require conversations between different groups of thinkers. “If students get offended because they’ve been told that they shouldn’t get offended or made to feel uncomfortable – I think they should absolutely be made to feel uncomfortable. That’s what university education is all about,” he says.

“Faculty should strive to foster difficult conversations inside and outside the classroom.” To that end, he has set up a “President’s Award for Constructive Discourse” for faculty who encourage “robust but honest, frank and respectful dialogue about topics you’re told not to discuss in polite company”. Winners can take home $1,000 (£840). In addition, he promises to support staff who face any sort of backlash from students offended by their words. “They will not be disciplined,” he says – as long as they acted in good faith.

“If you’re encountering new, challenging ideas, you’re going to feel uncomfortable,” he says. “And that’s OK!”

Most of the campus community are supportive of his stance, but Herbert has faced some pushback – albeit in small doses compared with other academics. “It’s strange for me because we’re at a university. But a few people believe that there’s a correct perspective on whatever the issues may be, and if you don’t adhere to it, you’re wrong and a bigot,” he says.

Calling out ‘nonsense’ in the trans debate

True to his word, Herbert is not afraid to wade into perhaps the most contentious issue of the moment: transgender rights. “I’m a big fan of letting people do what they want to do,” he says, but he does consider the issue of transwomen competing in elite athletics a “challenge”. He says the case of University of Pennsylvania swimmer Lia Thomas “raised questions” about the fairness of her record-breaking wins against cisgendered female participants.

“A lot of women have actually said that they fought hard for a separate division of women’s sport for a reason. But the trans community’s response is that if you even raise a question about that, you’re automatically a bigot. They assume it’s motivated by ill will, prejudice or bigotry towards trans people,” says Herbert.

Instead, he wants to “essentially declare ‘nonsense’”. “We need to foster an environment where we talk precisely about these issues. We don’t run away from them,” Herbert says. “We need to empower students and, frankly, the faculty to speak up and encourage these conversations – but in a civil way, not screaming at each other and making threats.”

Such “political polarisation and divisiveness” is a problem for the nation, he says. “It’s to the point of the country becoming not only almost ungovernable, but with people having a hard time talking about the things we ought to be talking about, because people are living in ideological bubbles.”

Challenging perceptions of mental health solutions

From his vantage, Herbert is well aware of the “mental health crisis among students”, which US data suggest has increased over the past decade. “Social media no doubt plays a role. Of course, the Covid pandemic also contributed,” he says.

Like most campuses, UNE provides services for those experiencing mental illness, but Herbert believes it takes a unique approach. “Our counselling is aimed more at building resilience, rather than the therapist trying to fix the problem.

“Even in services beyond counselling, we’re very intentional about empowering the students to solve their own problems, rather than solving it for them,” he continues. “I’m not suggesting this as a panacea, but I do think we’re on to something.”

“[Society] has inadvertently given young people the message that they’re fragile, and we’ve decreased their sense of self-efficacy to be able to cope with life’s problems.”

As children and teenagers, this generation of students was more closely supervised by their parents then previous cohorts, and as a consequence they have developed a “sense that they can’t cope on their own”, Herbert believes. “They didn’t learn how to deal with the normal challenges that come with growing up,” he says.

“Then you add that with the notion of safe spaces, the idea that we have an obligation to keep students not just physically safe, which goes without saying, but psychologically safe, that we need to make everyone feel comfortable,” he says. “The problem with that is that it again inadvertently gives the message that there’s an expectation that you should always feel comfortable, and if you don’t, there’s a problem, and you need to run to somebody else to fix it.”

Herbert is aware that his view might not be widely shared. “Part of the problem is that few university presidents want to articulate this model for fear of sounding unsympathetic. It’s much more nuanced than that.”

He sees how his approach could be perceived. “It could be misunderstood to mean that we’re suggesting that we’re blaming the victim, or that it’s the fault of people who have these problems,” he says. “That’s not what I’m saying, but simply that we need to build resilience to empower people, rather than give them messages of morbidity, weakness and fragility. We need to develop anti-fragility.”

Quick facts

Born: Alice, Texas in 1962

Academic qualifications: PhD and MA in clinical psychology from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro; BA in psychology from the University of Texas at Austin

Academic heroes: John McWhorter of Columbia University; Richard Dawkins of the University of Oxford; Steven Hayes of the University of Nevada, Reno; and Drexel University president John Fry

This is part of our “Talking leadership” series with the people running the world’s top universities about how they solve common strategic issues and implement change. Follow the series here.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login