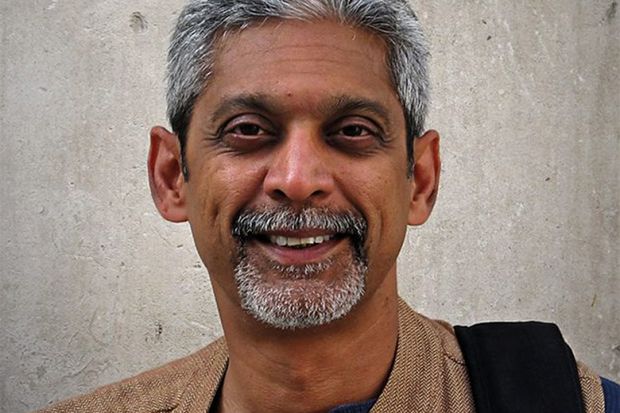

Vikram Patel is an Indian psychiatrist and professor of international mental health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He is co-founder of the Centre for Global Mental Health in London, co-founder of Sangath, a mental health research NGO based in Goa, and co-director of the Centre for Control of Chronic Conditions at the Public Health Foundation of India. His research focuses on delivering mental health care to poor communities. He was named among the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine in 2015, and was recently awarded the Pardes Humanitarian Prize in Mental Health.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in Mumbai (then called Bombay) in 1964.

How has this shaped you?

I was hugely fortunate that my parents and grandfather put enormous value not only on education but also on humility in the context of the gut-wrenching poverty and inequality of India. My mother, while being a pious Hindu housewife, was the most tolerant person I have known, and my values of social justice were heavily influenced by her.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

Quite frankly, a dissolute medical student, more interested in the beaches and hippy lifestyles of Goa than any purposeful vision for my life.

To what extent have attitudes towards mental health changed?

I think there is far more openness about discussing mental health problems and much less shame attached, although there is still too much stigma and discrimination. When I started work in India two decades ago, I was often challenged about mental health being a priority for a poor country or that it was a Western preoccupation with limited relevance to people in other cultures. The best indicator of the change in attitudes is the strong, and sensitive, attention to mental health in the media and the fact that I am no longer embarrassed – on the contrary, I am proud – to describe myself as a psychiatrist.

You spent some time earlier in your life working in professional theatre in India. Did you learn anything that remains useful in your work today?

I think my knack of being a good speaker could be partly attributed to my time in the theatre; to master the art of public speaking, there is no lesson as instructive as going out on to a stage facing an audience who paid to be entertained.

If you weren’t an academic, what do you think you’d be doing?

At the time, I had to make a choice after completing my schooling – my first preference was catering; however, my good grades and the fact that catering was seen as a profession for the “serving classes” in the days of my youth ensured that I found myself in medical school instead. I have always imagined myself running a bar, themed around African music – the only genre I can dance to with abandon – but I love my day job too much to give it up.

What event divided your life into “before” and “after”?

My two years in Zimbabwe immediately after I finished my psychiatric training in London. Working in a setting that had just 10 psychiatrists for 10 million people – and where most care for mental health problems was through traditional healers – was a strident wake-up call that I had to reinvent the practice of psychiatry from scratch.

Why has mental health not been a global health priority previously?

Mental health problems are quite hidden from view, in the sense that they are very private experiences of distress in comparison with physical health problems, and in that they do not materially appear to others to impact on the affected person’s life, with the exception of severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia. There is the notion that mental health problems are so entwined with cultural and social factors that their importance in non-Western or less resourced societies is uncertain, or they are unimportant. Furthermore, there has been the view that their diagnosis and management require very expensive personnel and sophisticated procedures. The work of global mental health practitioners has debunked all these myths, and the science of the field has greatly influenced the growing acceptance of mental health problems not only as being a hugely neglected global health priority, but also as a very tractable one.

How did you shift to your view that diagnoses for mental disorders are universal, rather than culturally specific?

Through my clinical observations in different cultures – in particular how the same interventions help people in diverse settings recover; through witnessing the impact of mental health problems in my closest friends and family; and through my research, which demonstrated unequivocally that mental disorders are not Western inventions but universal human conditions.

What is the worst thing anyone has ever said about your academic work?

That I was propagating an “imperialist” view by applying psychiatry to non-Western societies, and, in doing so, I was also furthering the commercial agenda of Big Pharma in opening new markets for their products.

Which fictional character do you identify with?

Baloo, the bear in The Jungle Book…but don’t ask me why!

What is the strangest letter or gift you have ever received?

A pair of “mojdis”, a traditional kind of footwear, from a physician in Pakistan who sent it with a note that this was a recognition that I was his “teacher” in the sense that my work had inspired him!

What advice would you give to your younger self?

To follow your heart as I have done through my life, even if it means swimming against the tide.

What would you like to be remembered for?

For demystifying mental health problems and their management; mental health is too important to be left to professionals alone, and I hope I will be remembered for generating the science that demonstrates how to realise this vision.

Appointments

Deborah Prentice has been appointed the next provost of Princeton University. A social psychologist, Professor Prentice is Alexander Stewart 1886 professor of psychology and public affairs. She became dean of the faculty in 2014 after 12 years as chair of the department of psychology. “I am honoured and excited” to become provost, she said, adding that Princeton had a “compelling vision of how we can build on the extraordinary strengths of this university in the years ahead, and I am eager to work with the entire university community to make this vision a reality.” She will begin her new role in July.

Andrew Neely will succeed Nigel Slater as the University of Cambridge’s pro vice-chancellor for enterprise and business relations. In the role, he will work to strengthen the university’s industrial and commercial relations. Professor Neely is an engineering fellow at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, leads the university’s Institute for Manufacturing and is founding director of the Cambridge Service Alliance. He held the first joint lectureship at Cambridge (between the engineering department and Judge Business School). “Universities make a difference in the world through their research, education and engagement, and I am looking forward to working with colleagues from across the university to help strengthen our relationships with large and small firms alike,” Professor Neely said.

Madelyn Wessel has been chosen as university counsel and secretary of the corporation at Cornell University. Currently university counsel at Virginia Commonwealth University, she will begin her new responsibilities in May.

Wendy Burn has been elected president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. She has served as dean of the college, and her clinical interest is in old-age psychiatry. Dr Burn will take up the role in June.

David Warnock-Smith has been named director of aviation, events and tourism at Bucks New University. He was previously a programme leader at the University of Huddersfield and has a background in the industry.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: HE & me

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login