In July, The Wall Street Journal published an exposé of the huge debts being accumulated by students doing master’s degrees in the US. Students pay annual fees of up to $100,000 (£75,000) for these two-year courses, and while academics were quick to rebut the suggestion that the master’s is a money-making scheme, the story went global.

In my home country of New Zealand, domestic students only pay about NZ$7,000 (£3,700) a year, rising to about NZ$28,000 for international students. But a survey by the New Zealand Ministry of Education in 2017 suggests that students may not see a return on this investment either. A master’s graduate will be earning about 30 per cent more than a bachelor’s graduate 10 years after graduating, but they won’t earn much more than someone with a postgraduate diploma, which is cheaper because it only takes one year to complete.

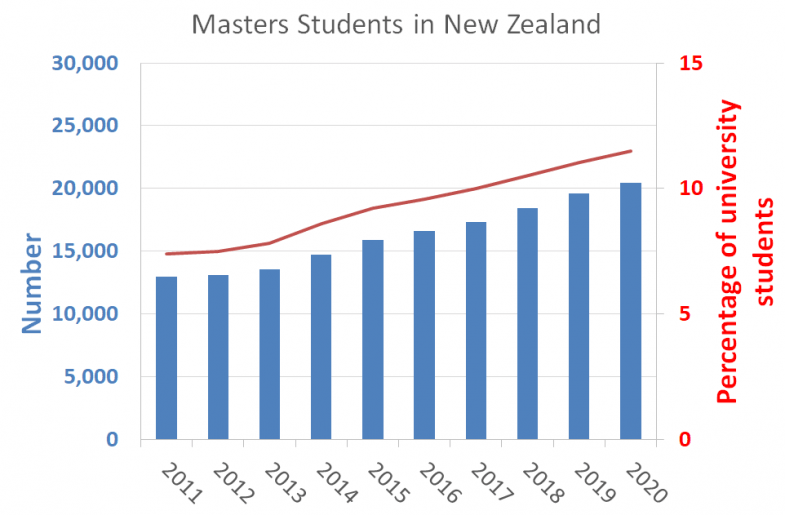

Despite this, the number of master’s students in New Zealand increased by 50 per cent over the past 10 years, accounting for more than 10 per cent of all university students by 2020.

There used to be two reasons to do a master’s: to become an academic or to earn the qualifications needed to enter professions such as medicine, law or veterinary science. Now, students also enrol in master’s degrees to prepare for careers in business, healthcare and government policy. Many students think they now need one to be competitive for a wide range of jobs.

The question is whether universities can deliver the educational experience all these students need. One type of master’s focuses on coursework. It teaches students advanced subject knowledge and skills. For arts and science graduates, a second type of degree combines research training with coursework. I think we need to redesign the latter.

THE Campus resource: Fostering interdisciplinary learning in large-scale doctoral programmes

In April, the New Zealand Productivity Commission found that postgraduates don’t have the sophisticated skill sets needed by the most productive New Zealand firms. Their workforce productivity (output per hour worked) is less than half that of comparable firms in other small, advanced economies, such as Sweden or Singapore. The commission recommended assessing the future needs of firms to build a better pipeline of postgraduate talent.

But that is not as easy as it sounds. We know, for example, that science postgraduates will need skills in the traditional sciences, plus data science and business skills. But a recent report by Graduate Careers in Australia found that employers struggle to predict what skills workers will need in the future.

New Zealand firms are expanding into niches in the export market, such as products with environmental and social credentials. This means they need creative postgraduates who have research skills in one discipline but can also look past traditional disciplinary boundaries and identify the best approach to meeting customers’ needs. Hence, master’s degrees should take a multidisciplinary approach. Theoretical courses should be co-taught by lecturers from different disciplines, on top of skills-based courses and seminars on how to learn new and complex sets of knowledge.

Our goal should be to teach students how to marshal scattered knowledge. Such training would be useful for students whether they are headed for industry or academia – because future academics will need to interact with industry to seek funding and to identify the skills that the students they educate will need in their careers.

It is also vital to address why only half of master’s students in New Zealand complete within the expected two years, according to Ministry of Education data. The reason appears to be that students doing degrees that combine coursework with research are taking too long to do the research for their theses. But is the production of such a document really useful for students who are not going on to academic careers? Enabling them to demonstrate their research skills should be the priority. Shorter assessments, such as literature reviews, proposals and seminars, would be more effective in that regard.

Overhauling the structure of the master’s degree is a win-win. Students will get the skills and the earnings premiums they seek, while universities will attract more enrolments – and fewer headlines questioning their value for money.

Catherine Whitby is associate professor in chemistry at Massey University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Make master’s a mixed bag

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login