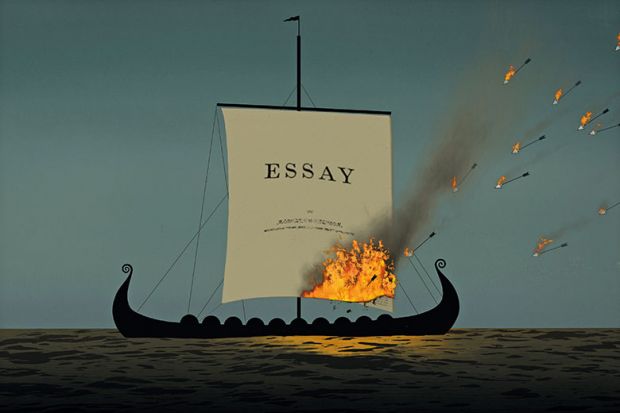

The suggestion that we should ditch assessed essays would once have been decried as heresy. Essays have been the mainstay of higher education assessment for many years, especially in the humanities, and have traditionally been thought of as the best way to assess a student’s ability to digest the literature on the topic in question and to use it to construct their own argument.

But then online essay mills came along.

Phil Newton’s recent research on the extent of “contract cheating” in the academy makes for sobering reading. Based on recent surveys, Newton, director of learning and teaching at Swansea University Medical School, concludes that as many as one in seven recent graduates across the world may have submitted assessed essays that someone else wrote. All this has only intensified the debate that has been raging online for the past few weeks over whether the assessed essay has finally had its day.

Banning the advertising of essay mills – one of Newton’s proposed solutions, in support of which a petition to the UK Parliament is currently circulating – might make some dent in essay mill usage. It is a measure that has already been adopted in New Zealand and is about to be tried in the Republic of Ireland. But, as someone with more than 40 years’ experience of thinking about higher education assessment, I tend to agree with those who argue that, in the face of such industrial-scale cheating, the only solution is to radically move the goalposts.

We can, of course, check whether each student really wrote the essay they submitted, by subjecting them to a mini oral exam regarding its contents. But that takes a lot of time. Adopting such a process as a matter of course would be all the more unacceptable given that academics and others already spend inordinate amounts of time and energy trying to assess essays and give feedback on them. I’m all for students getting feedback on their writing and thinking, but it needs to be provided in an efficient and focused way.

Moreover, marks need to be fair. And the fact is that we are demonstrably not good at grading essays fairly; I’ve checked this out many times in large faculty development sessions, and there has been abundant research over the years confirming it. This is why it may not even be wise to confine the use of assessed essays to exam conditions, where the scope to buy an off-the-shelf answer is much reduced. Essays are an inherently flawed form of assessment even when there is no question over their authorship.

I am not saying that essays have no role at all in higher education. In college-based tutorial systems, where they are the basis of dialogues between students and tutors, they can be invaluable. If essays were written only for such developmental purposes, with student assessment carried out via a different means entirely, feedback would be received without being distorted by feelings arising from a mark or grade. And there would surely be less temptation for struggling or hard-pressed students to take shortcuts and use essay mills.

Of course, contract cheating is not confined to essays. Just about any form of written product can be bought online, including postgraduate and doctoral theses, so just banning the use of essays in assessment would, perhaps, only be a first step in the fight against cheating. However, I suggest that the likelihood of unfair practices being involved diminishes when the written work is more complex and distinctive to the student.

But wouldn’t banning assessed essays curtail universities’ ability to teach students to write grammatically and fluently? Perhaps. But many employers and commentators already grumble that institutions are deficient in this role. And perhaps this is unsurprising in a world where online communication is far more frequent than extended written communication, and where the need to propose an argument or defend a proposition is linked to brevity and careful choice of wording.

Best practice in assessment has developed strongly over the past few years, across many areas of higher education. This centres on allowing students to demonstrate the application and use of knowledge in context; examples include asking them to write draft journal-style articles, compile portfolios of evidence and write up “live” case studies, where the sources of information are still evolving, collaborative or difficult for someone external to access.

Yet in some disciplines and institutions, old assessment methods that don’t add much to student learning remain perniciously hard to combat. Examples include traditional, formulaic lab reports and true-false tests, but essays are the most ubiquitous. If our mission as educators is to help students to develop their array of lifelong-learning skills alongside their mastery of subject content, we need to ensure that we spend our time and energy more profitably. It is time to step off the essay treadmill.

Phil Race is a writer and speaker on assessment, feedback, teaching and learning in higher education. He is a visiting professor at Edge Hill and Plymouth universities and emeritus professor at Leeds Beckett University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: It’s time to write off the essay as a way to gauge learning

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login