The cost of attending a university is an important factor in students’ education decisions and governments’ access strategies. Although much debate focuses on tuition fees alone, the policy landscape in Canada is highly complex and would benefit from better alignment.

Regarding tuition fees, there is a remarkable range of “sticker prices”. On average, undergraduate tuition plus compulsory “ancillary” fees for Canadian citizens and permanent residents in 2017-18 are C$7,451 (£4353) a year. But since provincial governments are responsible for education, this average masks enormous geographic variation. Mean provincial undergraduate tuition plus fees range from C$3,652 in Newfoundland to C$9,389 in Ontario.

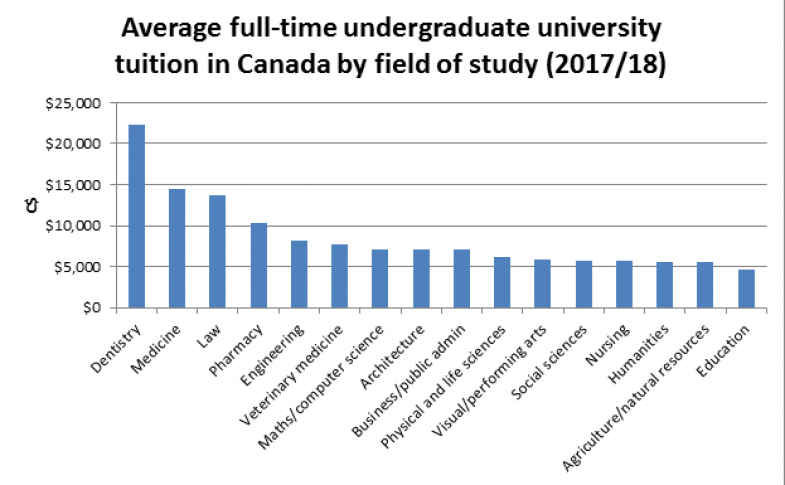

Moreover, within many provinces, tuition fees vary widely across fields of study, with professional programmes such as medicine and law typically having the highest charges. One of the largest variances is in Ontario, ranging from C$6,606 in humanities to C$12,083 in engineering, and to C$38,516 in dentistry. Even in Newfoundland, where students in most fields of study pay a flat C$2,550, medical students pay C$8,250.

Within some provinces, tuition rates also differ between institutions for the same fields of study. In Ontario, full-time first-year social science undergraduates at the University of Ottawa are charged C$7,291, whereas students at McMaster University pay C$7,771. This masks yet another peculiarity: McMaster charges lower tuition fees for first-years than for those in later years, whereas Ottawa does not.

Tuition, however, does not fully determine the cost of university attendance, since a large percentage of domestic students benefit from some form of subsidy. Each university operates its own scholarship and financial aid programme; for instance, of the University of Guelph’s almost 28,000 students, about 7,500 receive university merit- or needs-based funding. Additionally, each province, as well as the federal government, operates financial assistance programmes providing needs-based grants and loans.

Canadian governments also employ substantial tax expenditures/credits of appreciable value to students. While there are some benefits to these mechanisms, they also make the entire system much more complex and less transparent. (Canadian trivia: these tax expenditures started in the 1950s, arguably as a mechanism by which the federal government could “get around the constitution” and spend in areas of provincial jurisdiction.)

There are clearly some advantages to a wide variety of policy levers. And pricing flexibility at the institution level (within the boundaries, of varying strictness, set by provincial governments) allows a limited form of competition that is arguably beneficial.

However, in part, the opacity of the (non-)system means that most prospective students do not have good information for making decisions. Even policymakers do not fully understand the combined effects of all these various prices, grants, loans, tax expenditures and other policies.

In recent years, the federal and some provincial governments have substantially restructured their loans and grants systems to make them more generous to students from low-income families. They have “paid” for this by reducing or eliminating tax credits that largely benefit high-income families.

As pointed out by our colleague Alex Usher, predicting the actual winners and losers from these complex changes is far from straightforward. Still, these reforms probably have been beneficial, and (partly) align with long-standing calls to make post-secondary education more equitable.

But, particularly in some provinces, further policy alignment is necessary. While Canada’s decentralised federation makes coordinated, system-wide post-secondary reform difficult, a deep and careful examination of the combined effects of the entire package of policies that impacts the cost to students would be worthwhile.

Provinces will undoubtedly make different choices in any future reform given their diverse populations, situations and values. However, improved understanding of the impacts of the current policy thicket, and more cooperation between federal and provincial governments (and across ministries within each government), would benefit everyone.

And aligning government pricing and student aid instruments and policies could allow for a better balance between the goals of improving access and funding quality education. Helping students to understand actual costs would be a bonus.

Ross Finnie is director of the Education Policy Research Initiative (EPRI) and a professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Ottawa. Richard E. Mueller is associate director of EPRI and professor of economics at the University of Lethbridge. Arthur Sweetman is associate director of EPRI and professor of economics at McMaster University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Align prices to achieve balance

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login