Browse the full results of the World University Rankings 2024

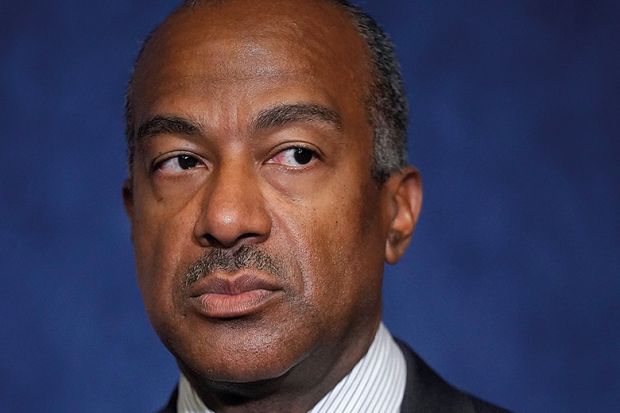

In the aftermath of the US Supreme Court rejecting race-based considerations in US college admissions, Gary May probably has as good a read as anyone on the seriousness of what US higher education now faces.

May is the only black chancellor in the renowned University of California system, serving since 2017 as head of its northernmost campus, UC Davis. He came to California after three decades at the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he served as dean of the nation’s “largest and most diverse” college of engineering.

Yet racial diversity has remained a persistent struggle at UC Davis. With California voters having imposed their own ban on affirmative action in admissions back in 1996, the campus has managed a 4 per cent enrolment of black students – below the 6 per cent level of the state-wide population.

The reasons for that, May suggests, are complicated. Part of it is the overall strength of the UC system: while UC Davis is rated as highly selective, students competitive enough to be admitted there often find another of the UC’s top-ranked campuses at least as attractive.

“Even the ones that we do accept have multiple choices,” May says. “They’re probably accepted at every UC that they applied to, as well as [the University of Southern California] and Stanford and other places,” he says. “So they have choices and sometimes they have a better, either financial or other, circumstance at one of their other choices, than they would at Davis.”

It doesn't help that the city of Davis is fairly small and its surrounding region is rural – generally not attractive features for black students from urban areas. “We have to do a little bit of salesmanship to get students who come from those backgrounds to be interested in Davis,” May says.

And there’s inertia – the catch-22 in which a low percentage of black students makes it less likely for others to join them. As May explains it, “you want to have an environment where students feel like there’s a community – and one of the ways to build community is to have a critical mass.” But, he says, “you can’t have a community where there’s only a handful of people.”

On top of that, there’s the even more difficult questions about capabilities. UC Davis can admit only 6,000 first-time freshmen each year out of 110,000 applications, plus another 3,000 transfer students, May notes. “It’s just a competitive environment,” he says, “and so students with disadvantaged backgrounds have a lot of competition to overcome to be enrolled.”

Fortunately, Davis has a good model to emulate: its own medical school. For the past decade, the UC Davis Medical School’s assessment of its applicants has included the use of a socioeconomic disadvantage scale that ranks candidates from zero to 99 on a combination of factors that cover family wealth, neighbourhood condition and parental education.

The result is an entering class that – despite the state’s 1996 ban on racial preferences in admissions – is 14 per cent black and 30 per cent Hispanic, well exceeding the national average. US medical schools graduated 10 per cent black matriculants and 12 per cent Hispanic matriculants in 2023, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“Those are not explicitly race-based,” May says of the measures in the Medical School’s socioeconomic disadvantage scale, “but they make pretty good proxies for race, and allow us to have the most diverse medical class in the country that’s not at a HBCU [historically black college or university] or a minority-serving institution.”

May is now trying to translate that success to the overall UC Davis campus, asking his administrators for a formal assessment of the possibilities and legalities. None of it seems straightforward. In addition to the difficulties of getting minority students to choose UC Davis, the threat remains of more US Supreme Court action on the topic.

In its ruling last month against race-based considerations in college admissions nationwide, the conservative-dominated top US court did hold out the possibility of letting institutions make assessments of “how race affected the applicant’s life, so long as that discussion is concretely tied to a quality of character or unique ability that the particular applicant can contribute to the university”.

Experts have said it’s not clear how the Supreme Court might eventually apply that logic to specific cases, such as that of the UC Davis Medical School, with likely new legal challenges. In the meantime, some of those experts have warned institutions against making statements that acknowledge that their policies do have predictable effects on racial percentages.

That problem aside, May recognises that a key to success with minority enrolment is the retention of those who do get admitted and then accept. UC Davis’ struggles to recruit and keep its minority students have been publicly highlighted by Ebony Lewis, chief strategy officer at the university's Office for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, who used her 2021 doctoral thesis to chronicle the reasons why black students avoid UC Davis, and has been leading on brainstorming ways to fix that.

One of UC Davis’ chief efforts in that direction, May says, is its “Summer Bridge” programme, which gives selected freshmen an eight-week head start on their college careers.

Another is UC Davis’ partnerships with minority-serving institutions. Although the campus doesn’t have the wealth of nearby HBCUs that May enjoyed at Georgia Tech, it’s been creating similar relationships with local community colleges, including a branch of Sacramento City College that’s right at UC Davis. “You partner with places where those students are being produced, to do your collaborative programmes and recruiting,” May says.

And the concern isn’t just for black students, May says. More than a third of the California population is Latino, and yet that racial group represents just under 30 per cent of the student population at UC Davis, he says. Even white students are underrepresented on the campus, owing to the disproportionately large number of ethnic Asian students, he says.

A third strategy for raising minority enrolment at UC Davis, May says, centres on creating a critical mass of minority faculty who can serve as teachers, mentors and role models. High school seniors don’t necessarily consider such things when they choose a college. “But when they get there, it becomes a factor,” he says.

Although May prefers not to antagonise state lawmakers, he allows that there are ways in which the legislature might be more helpful. California lawmakers prioritise education for the state’s residents by requiring that in-state students get at least 82 per cent of the university’s slots. May understands the value of such a move, but also acknowledges that it limits his flexibility in expanding black enrolment, preventing him from admitting more qualified out-of-state minority students.

“They’re very unsympathetic to arguments for any of the UCs trying to recruit non-California residents,” he says of the state’s policymakers. “Those arguments are not really heard.”

May argues that it’s also possible for the state government to boost financial support aimed at attracting black students, even temporarily, to help build the critical mass he feels would help ensure a long-term gain in black enrolment. But that doesn’t seem likely in the current financial circumstances, he acknowledges.

Overall, being the UC campus closest to the state capitol in Sacramento has pros and cons, May believes.

“It’s a double-edged sword – it gives us a little more access, but it also gives us a little more scrutiny at the same time,” he says. “I’ve been on both sides of it, but overall, I think on balance it’s a good thing.”

paul.basken@timeshighereducation.com

This is part of our “Talking leadership” series with the people running the world’s top universities about how they solve common strategic issues and implement change. Follow the series here.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login