Academics nursing their wounds after coming through another gruelling assessment round might baulk at the idea that this period should be one of joy.

Students may complain about the work they are expected to do, but the burden of setting assignments, marking them and then dealing with increasing numbers of appeals is placing a strain on teachers too.

And there is a sense across the sector that things only seem to be getting worse as universities facing questions such as how to make graduates more “job-ready” often alight on the same answer: more assessment.

Despite all that, Jan McArthur, senior lecturer in education and social justice at Lancaster University, believes that – if assessment is done right – joy is exactly the emotion academics could be feeling right now.

“What they are doing is looking at that moment of their students’ achievement. It should be really joyous,” she said.

“Even if their student hasn’t achieved, there should be a joy in a teacher thinking: ‘This student hasn’t understood yet, but I can help them.’”

Instead of joy, however, assessments often conjure up feelings of stress, panic, helplessness and exhaustion for all involved. “If you talk to an academic during assessment time, it is doom and gloom and horrible,” Dr McArthur acknowledged.

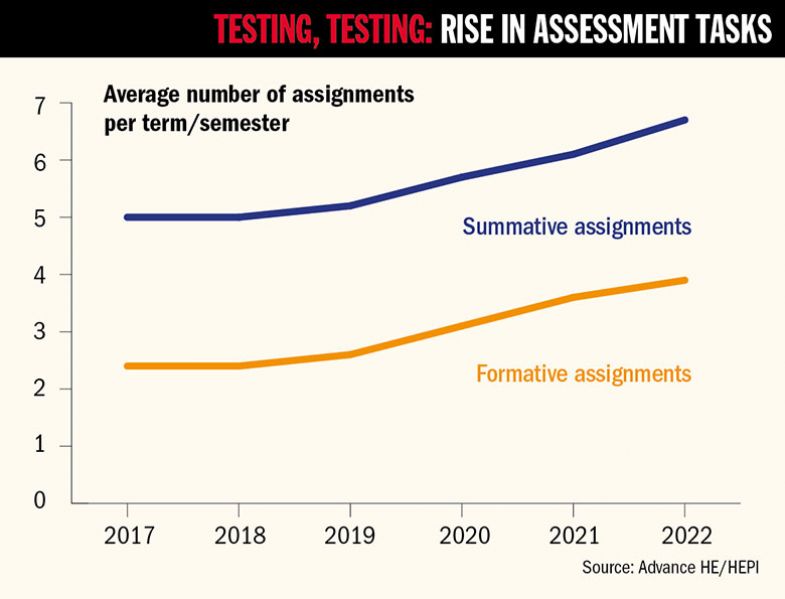

Part of the problem is the proliferation of assessments seen in recent years. Amid recognition that students do not fare well when faced with the prospect of one end-of-year exam that can make or break their academic career, many universities have switched to a model that features more assessments with lower stakes, often a mix of projects, exams, essays and presentations. While many of these are summative assessments, meaning that they contribute to grading, there has also been significant growth in the use of formative assessments, which are used to provide ongoing feedback.

THE Campus resource: Why you should write feedback to your students before they've submitted

A 2018 study by Carmen Tomas, of the University of Nottingham, and Tansey Jessop, now at the University of Bristol, found that students at research-intensive institutions across the UK typically completed 50 summative assessments over the course of their degree, although there was wide variation between subjects, with one mathematics degree involving a stunning 227.

The UK’s latest Student Academic Experience Survey, run by Advance HE and the Higher Education Policy Institute, found that the volume of both summative and formative assignments reached record highs in 2022. Among the 10,142 undergraduates who participated in the survey, the average number of summative assessments per term was put at 6.7, compared with 5.0 in 2017; while the number of formative assessments rose from 2.4 to 3.9 over the same period.

Comments in the survey indicated that students felt unprepared for how much work they would have to do, that deadlines were “all over the place” and that work-life balance was unhealthily out of kilter.

Students are now in a situation, Dr McArthur said, where they feel “under a constant state of anxiety” because there always seems to be an assessment due.

“It is more prevalent in some disciplines than others, but it is becoming more prevalent across the board. As soon as you get one assessment in, it is on to the next one. The time for contemplation, reflection, rewriting mistakes – all the things we know are essential to good learning – there’s no time for them any more,” she said.

This is a phenomenon that is experienced in higher education systems around the world. As universities – often compelled by governments – have placed greater emphasis on learning outcomes, assessment has assumed an ever more important role, according to Rola Ajjawi, associate professor in educational research at Australia’s Deakin University.

“What you end up doing is designing your assessment so that you can prove that you have assessed every learning outcome in a unit of study…What that’s done is, I think, led to more over-assessment because we are trying to ensure every single learning outcome is covered,” she said.

For Dr McArthur, the system of assessment now used across higher education has been “cobbled together” via the accretion of “incremental” changes over time and has become too far removed from the fundamental purpose of the exercise.

“I think there’s a lot of people trying to do what they are told is good practice, but because it is all incremental, it is creating something that was not intended at all,” she said.

“There’s a feeling that, ‘We have to have a presentation because we’re told to assess presentation skills, so we’ll stick in one of those.’ And they do that and it’s well-meaning, but it is not coherent.”

Mary Richardson, professor of educational assessment at the UCL Institute of Education, agreed that academics’ keenness to embrace new and different ways of doing things had often added to the workload.

She said new elements have been added to courses alongside, rather than instead of, traditional forms of assessment, which are still often considered to be the gold standard by the population at large.

“There are lots of great ways to assess students, but our general public and societal approach is still very, very conservative and old-fashioned,” Professor Richardson added.

“We’re encouraged to be more diverse and think about what we are doing, but that is not necessarily reflected in what students or employers want. There is a constant tension about, ‘What kind of grade is this, and is it comparable?’”

Ms Tomas, the author of the 2018 study, argued that the modularisation of courses posed challenges for institutions when assessing students.

“We are trying to promote an understanding of how the accumulation of assessments across modules looks and feels for the student,” said Ms Tomas, until recently associate director of educational excellence at Nottingham and soon to be an honorary assistant professor of education there.

“We need to take a programme-level view and gain a better understanding of what the student is doing across their studies. A better balance is needed, but the challenges we experience are deeply ingrained in our systems.”

Most agreed, however, that the way to fix the problems of over-assessment was not by reintroducing high-stakes final exams, maintaining that continuous testing could work if assignments were better planned and thought out.

For Dr Ajjawi, assessments should be more sequenced and should feed into one another so that students can use feedback to better inform their approach to the next piece of work.

Introducing an element of choice could also be crucial, with students potentially being given the option to pick between several forms of assignment. “Our approach to fairness is that everyone must sit the same exam. But actually, that’s not promoting equity because our students have diverse needs, so we are not designing choice or distinctiveness for individual students into assessments,” Dr Ajjawi said.

THE Campus resource: Strategies for the constructive use of various assessment methods

Professor Richardson said she has been trialling a new technique with undergraduates, known as patchwork test assessment. This involves students being given questions at the start of term and set to work on writing them straight away, completing short pieces on which they receive rapid feedback from tutors and peers. This ensures that by the end of a 10-week module, they already have half the assignment written up.

Dr McArthur agreed that such portfolio-based assessment, where students build up a body of work over time, could be more flexible and less stressful for those taking part.

At Nottingham, the idea of involving students more in their own assessment, rather than seeing it as a process that is done to them, is also being trialled.

Ms Tomas said students have been trained to self-assess and peer-assess and have been given a role in planning, with the aim of helping them gain a deeper understanding of standards and performance.

If students’ stress levels are to improve, better coordination across courses is needed, most academics agreed. Dr Ajjawi felt that summative assessments should be decoupled from units of study so that each test, essay or project could draw on multiple units at the same time.

But such bold changes require bravery, and hopes that things would be different post-pandemic are fading.

In fact, there is a sense that to compensate for a lack of face-to-face contact, and to address concerns about upholding academic integrity in an online environment, universities responded to the Covid challenge by introducing more testing.

There is much that can be learned from student feedback – such as that they appreciate a more relaxed approach to granting extensions – but questions remain over whether any institution is really prepared to challenge the status quo.

“The problem with assessment is that it is so important that people are frightened to change it, other than in ways that reinforce the same old system,” Dr McArthur said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Is assessment burden causing hard-pressed students to wilt?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login