During this pandemic, many lecturers have learned a whole lot more about the pros and cons of distance learning, and many have become more proficient at teaching online. While the arrival of a coronavirus vaccine will allow faculty and students to return to in-person classrooms without masks or two metres between desks, this experience can’t help but change some of our teaching practices.

Let me first emphasise that I disagree strongly with those who predict that the recent widespread use of online classes will doom residential education. There is great value to in-person learning, whether in a formal classroom or late at night when friends debate an important issue. We communicate with more than our mouths; we communicate with our whole bodies, and when you can see an entire person, you understand better what they are saying and how they feel about their argument. Furthermore, there is a spontaneity in physical conversion that can produce a different discussion. Groups that are physically together react differently from groups linked by video. We get to know people more intimately when we see all of them.

The research clearly indicates that online education works well for people who know why they are engaging in a topic and have a clear view of what they want from their education. That’s why online professional master’s degrees work so well. But among 18-year-olds who engage in college entirely via online classes, the failure rate is very high. When you are exploring your options, and still figuring out who you are and what you want to do, a residential college experience can be a far better choice.

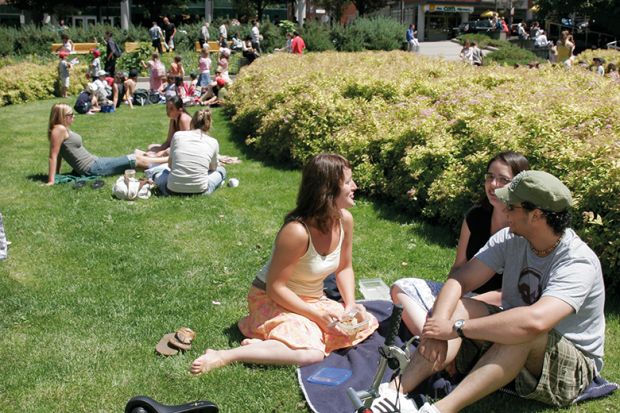

That’s because residential education is about far more than class content. It’s about making new friends, often from very different and more diverse backgrounds than you experienced growing up. It’s about living independently from your parents, figuring out how to turn strangers into roommates and friends, and engaging in a wide variety of extracurricular learning experiences through student-led organisations, social events, internships, community engagement or research projects with faculty and staff mentors.

But saying that residential education will have enduring value isn’t the same as saying that our recent foray into all-online learning will have no impact. There are at least three important ways in which university teaching will change.

First, faculty have learned new teaching strategies that allow them to make use of educational technologies in ways that improve learning. There are places where pre-recorded lectures are appropriate, allowing faculty to spend precious class hours in much more direct engagement with students. I suspect that more faculty in the future will opt for the “flipped classroom”, where students are expected to listen individually to lectures that present substantive material beforehand, then come together in person for more active learning. This may mean working together on problems, working through the applications and implications of the material, or debating the ideas presented.

Second, we will be less bound by time and space in our interactions with students. The pandemic has moved us all into a world where preset schedules are less important. Lectures are often asynchronous, so students do not have to be in class between 11am and 12pm on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Academics’ “office hours” have become much looser, scheduled at the convenience of both faculty and students. Advising appointments are similar. Nobody has to appear in person; indeed, many of these meetings are currently happening between teachers and students on different continents.

I fully expect that video meetings between faculty and students may become the norm. Graduate students in particular tell us that they are delighted not to have to spend 30 minutes getting to a 15-minute meeting. While scholars will want to protect their non-teaching time, they will be more open to quick conversations or email exchanges. On our campus, faculty report that in recent months they have been spending more time than ever in one-on-one meetings with undergraduates. Students will not be lined up outside a faculty member’s door. However, face-to-face meetings might still be needed to work through problems where visualisation matters. This can occur when trying to explain how to solve a technical or mathematical problem, where watching a student solve it can tell you where they are going wrong, and where a teacher might want to grab the pencil and sketch out an alternative approach. Our technologies still make this type of interactive learning more difficult online.

Third, the growing comfort with distance learning will mean that the availability of online classes and degrees will accelerate. I expect that many institutions will expand their online degrees, both for undergraduate and postgraduate students. More programmes will offer hybrid options, where students can take a combination of in-person and online classes. In fact, I suspect that many universities will advertise that enrolled students can complete their degree even if they are not able to attend in person. With older adult learners, the advantage of this flexibility is obvious, but even for younger students this flexibility could allow them to study abroad, take on internships, or manage family responsibilities while still making academic progress.

The challenge for us all in this evolving world is to make sure we are effectively pursuing our educational mission even as modes of instruction become more diverse. As we all know, it is possible for teachers to teach poorly, both in person and online. Monitoring the quality of these different approaches will be important. We need to make sure that lecturers have the skills and tools they need to develop high-quality digital content.

I end with a word of warning. Some believe that greater use of online tools will result in lower costs for higher education. I see little reason why this should be true, at least for institutions that care about quality of learning. Teachers will spend as much – and perhaps even more – time preparing to teach in this new world. We know that large classes in which students simply absorb content by listening are generally far less effective than classes in which students interact with the material – working on problem sets, writing essays, constructing projects or discussing ideas. This requires class sizes that allow student/lecturer interaction.

When we are past this very odd time of physical distancing and dispersed learning, we need to assess what this experience has taught us. Smart teachers and good universities will take advantage of the new skills and the changed mindset that this pandemic has produced, to provide even better educational opportunities for their students.

Rebecca Blank is chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2021 will be published at 12pm BST on 2 September. The results will be exclusively revealed at the THE World Academic Summit, which will explore the challenges created or accelerated by the pandemic and identify new opportunities for progressive reform.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: This is not the end of residential education

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login