A global goal of ensuring equal access to higher education by the end of the decade is now “highly unlikely” to be met, with progress seemingly going backwards because of an “equity crisis” fostered by the pandemic, according to a report.

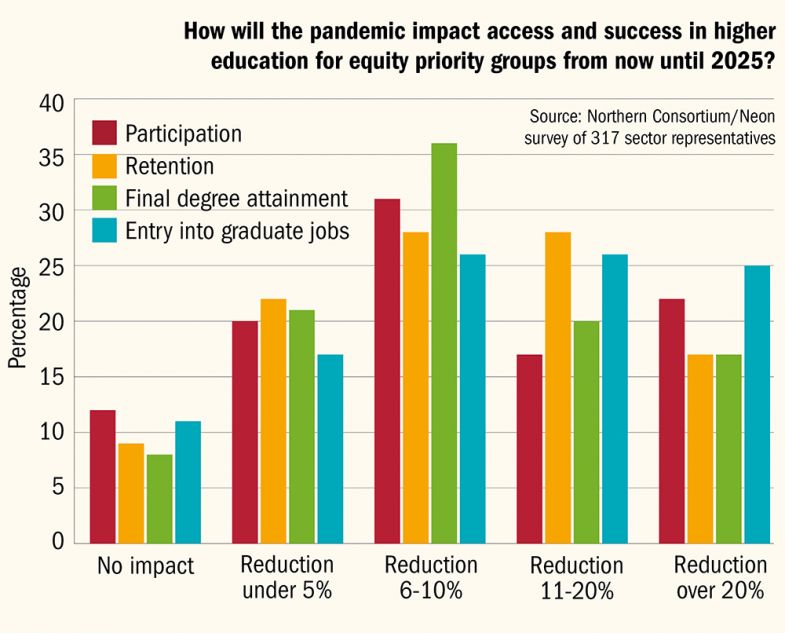

Hundreds of university representatives in more than 50 countries told a survey that they are seeing lower participation, higher dropout rates, poorer degree results and a reduced likelihood of getting a job after graduation for those from more disadvantaged backgrounds, compared with before the Covid-19 outbreak.

The National Education Opportunities Network (Neon) findings – produced for the Northern Consortium on World Access to Higher Education Day on 17 November – raise serious doubts over whether a target included by the United Nations in its Sustainable Development Goals will be met. This commits countries to “by 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university”.

Applications down, dropouts up

Graeme Atherton, the report’s author and director of Neon, said he had seen “no evidence” that the goal was close to being reached, adding that the available data show “how far you are away from anything that approaches equity”.

While a few countries were making some progress, there was a “worrying” lack of significant global policy engagement and few mechanisms in place to share best practice on a world stage, Professor Atherton said.

“It is something of a crisis really, particularly as things globally appear to be getting worse, not better,” he added.

Among other key findings:

- More than 80 per cent of survey respondents say applications from priority groups to higher education in the organisation they work for have fallen during the pandemic. A quarter say this fall has been more than 20 per cent.

- About 90 per cent of respondents thought that between now and 2025 things were likely to get worse for these groups, with participation decreasing, attainment falling, student dropouts rising and progression to graduate employment declining.

- Those from a lower socio-economic background were the group respondents feel were most likely to have been most negatively affected by the pandemic.

Work being done to avert the “crisis” is not sufficient, the report finds, with only 20 per cent of countries having policies in place to address inequalities faced by some citizens in accessing higher education and achieving success once there.

At an institutional level, efforts to address the issues are also found to be lacking. Only 25 per cent of respondents describe the financial support on offer to disadvantaged groups as “significant” while only 30 per cent say the same about their organisation’s outreach work.

Professor Atherton said the pandemic had both dented learners’ progress and distracted institutions from focusing on the issue, with leaders instead putting their efforts into challenges such as recovering international student numbers and coping with economic challenges.

“What happens then is the issue of access gets relegated down the priority list, and it wasn’t high in the first place,” he added.

The report calls for a “culture change” across higher education, expressed in “concrete financial commitments” – rather than just statements of intent – and suggests universities invest 5 per cent of their annual income in boosting access.

A global task force should also be created by 2024, the report recommends, including influential global organisations that can “galvanise commitment” from policymakers and universities.

Finally, it calls for target-setting to become the norm, alongside efforts to address the patchy data collection that is found in all but a minority of countries.

“If you don’t address some of these issues, it challenges the legitimacy of higher education as a whole,” said Professor Atherton, head of the Centre for Inequality and Levelling Up at the University of West London.

“If it becomes entrenched as only serving parts of the population, other parts will become resentful of that. That has already happened a bit possibly in the US and the UK and can happen in other areas.

“If higher education is seen not as a force that reduces inequality but one that reinforces it, it makes us open to some of the populist political strategies we have seen in recent times.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: World ‘going backwards’ on access

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login