Several European higher education systems appear to be closing the gap with the UK on international student recruitment, with some even beginning to attract more learners from outside the continent.

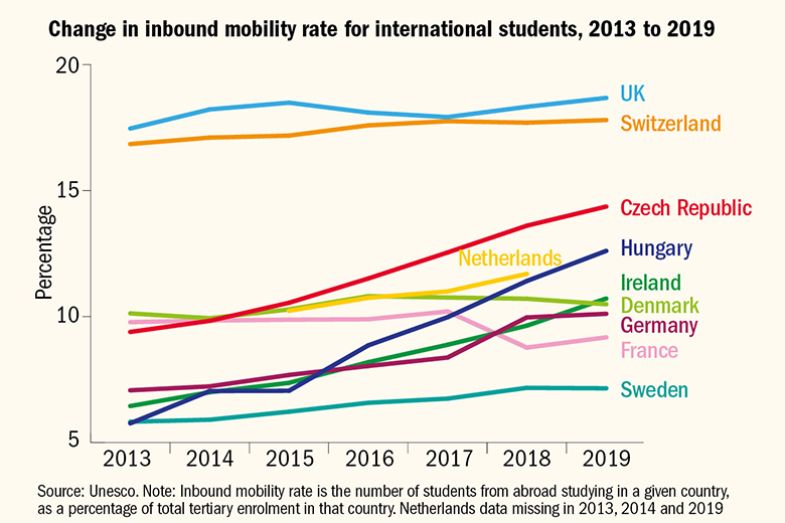

Data from the UN’s Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation show the UK’s inbound mobility rate – the number of students from abroad as a percentage of total tertiary enrolment – has remained broadly static since 2014 at around 18 per cent even as absolute international numbers have increased.

But the figures show that a number of nations in continental Europe that around a decade ago had much lower inbound mobility rates have been rapidly internationalising their student cohorts.

They include newer members of the European Union such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia and Latvia – where the mobility rate has climbed to above 10 per cent – but also some older members like the Netherlands, whose latest figures in 2018 showed 12 per cent of all tertiary students were from abroad compared with just 4 per cent in 2010.

The underlying data suggest many of these countries have internationalised their campuses by, like existing continental learning hubs such as Switzerland, accepting more students from within Europe. In the Netherlands, well over half of international students are European and in Denmark and the Czech Republic this figure is 80 per cent.

But others appear to be increasing their international students from other parts of the world. For instance, in 2015 in Germany, 42 per cent of learners from outside the country came from Europe, but this fell to 32 per cent in 2019.

Two other countries whose inbound mobility rate has been quickly increasing, the Republic of Ireland and Hungary, also had relatively high proportions of international students from Asia, at 47 per cent and 40 per cent respectively. Ireland is one country where universities have been explicitly pushing to recruit more students from China.

Michael Gaebel, director of higher education policy at the European University Association, said mobility statistics had to be treated with some care because, if they used citizenship to estimate incoming numbers, this could mean some groups, like the children of migrants who moved some years earlier, were classified as international students. It was also important to differentiate between mobility for full degrees and short-term exchanges.

But he said it was true that European higher education systems had been diversifying their intakes as factors such as the growth of English-language courses and lower or no fees in some countries attracted learners from across the world.

“Mobility is much more diversified than it used to be. Over the last two decades I think students have discovered the wide range of diverse possibilities” in where to study, he said, adding that, for example, “Finland wasn’t a popular study destination some 15 or 20 years ago. Nowadays it is.”

A key trend to watch now, he said, would be how the pandemic and the shift to online learning affected such mobility trends.

A report published by the British Council and Studyportals last month said the growing number of courses now being taught in English around the world meant almost one in five English-medium degree programmes were now outside Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US.

However, the increased international mobility aided by such growth is causing tensions in some European countries, most notably the Netherlands, where limits on capacity are sparking a debate on whether measures are needed to curtail international recruitment.

One of the possible ideas being considered in the Netherlands is to limit the number of courses in English, but while agreeing on the value of language diversity, Mr Gaebel was unsure that this would reverse the trend given the global demand for such programmes.

“Talking to colleagues in the Netherlands, no one can imagine a future without teaching in English,” he said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: UK losing its lead on international mobility as Europe closes gap

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login