As voters in the UK, France, Germany and the Netherlands go to the polls this year, some politicians and commentators want to tip funding and attention away from higher education and back towards vocational training.

In a worrying sign for universities, a unique pan-European survey suggests that this is a shift that would have widespread public support.

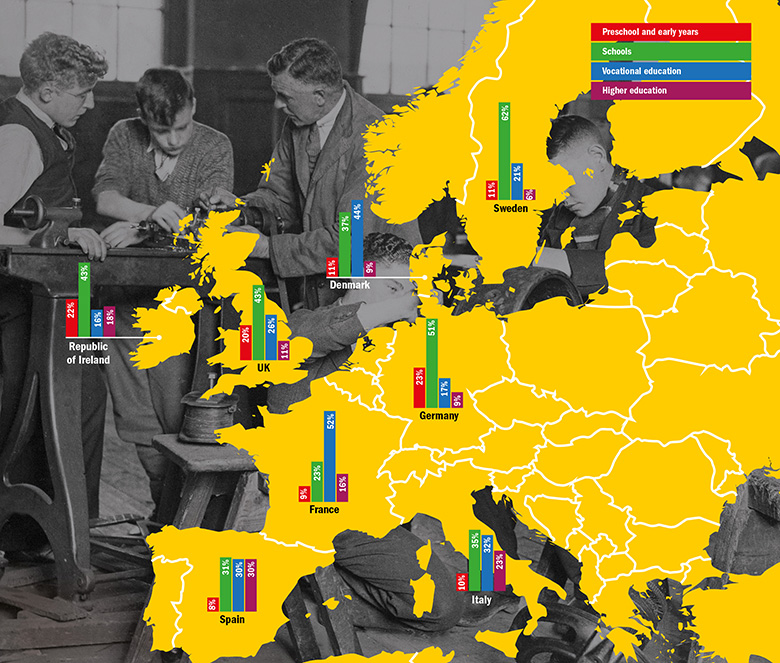

The survey of nearly 9,000 citizens in eight European countries reveals that, when forced to prioritise one area of education, only 17 per cent chose higher education, compared with 30 per cent who want more vocational education and training (VET). Thirty-nine per cent backed general schooling and 15 per cent preschool.

Support for prioritising higher education was highest in Spain (30 per cent) and Italy (23 per cent), and lowest in Sweden (6 per cent), Germany and Denmark (both 9 per cent).

Marius Busemeyer, a political scientist at the University of Konstanz who helped lead the research, said: “I was really surprised that [support for] VET is holding up so well.” Despite the focus in recent decades on higher education expansion, “people still care a lot about VET”.

Enthusiasm for vocational training could be a reaction to the enormous expansion of universities, Professor Busemeyer suggested. “If you have strong increases in spending in one field, then people tend to oppose further funding” and to “feel that more attention needs to be paid to other sectors”.

In Germany, there have been concerns that higher education is chipping away at the traditionally very strong vocational system: one prominent critic, the philosopher Julian Nida-Rümelin, coined the term Akademisierungswahn – loosely translated as academic delusion – to attack a supposed excessive focus on higher education, a term that has found support in the right-wing party Alternative for Germany.

It is “no longer the case” that the apprenticeship and vocational system is attractive enough to compete with higher education, said Professor Busemeyer. In 2013, for the first time in German history, there were more students than apprentices, he added. Some apprenticeship positions have gone unfilled.

What’s your priority? Pan-European survey reveals continent’s education funding priorities

Source: representative survey of 8,905 individuals cited in M. Busemeyer, J. Garritzmann, E. Neimanns and R. Nezei, “Investing in education in Europe: evidence from a new survey of public opinion”, Journal of European Social Policy, 2017. Minimum of 1,000 respondents per country. Figures have been rounded.

Meanwhile, in the UK, where complaints that too many young people go to university are still frequently made, the Conservative Party, ahead of the general election on 8 June, pledged a “major review” of funding across tertiary education as a whole. Although details are lacking so far, this could signal a diversion of money away from universities in favour of further education colleges and proposed new institutes of technology.

High levels of youth unemployment across southern Europe could also be driving support for vocational education there, said Professor Busemeyer. When asked why they backed some forms of education over others, respondents “care mostly about jobs”, he said.

This “bumpy transition from school to work” in France – where nearly a quarter of young people are unemployed – could help to explain why more than half of French respondents thought vocational education was the top priority, said Małgorzata Kuczera, a project manager of reviews into apprenticeship and basic skills at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Many French degrees also had a low labour market value, she added, while VET was “underdeveloped” at upper secondary level – all explaining strong French support for more vocational spending.

But in Italy and Spain, where youth unemployment is even higher than in France, people are more supportive of higher education. This could be because vocational training was still of low status and attempts to improve it had not worked, said Professor Busemeyer. “In Italy, maybe people think it’s simply not a viable option to build it up,” he explained.

Search our database for the latest global university jobs

The survey results, published as “Investing in education in Europe: evidence from a new survey of public opinion” in the Journal of European Social Policy, may not reflect current opinion perfectly, as the poll was conducted in 2014. But it is the first survey to try to understand exactly which types of education the public value, rather than just looking at support for education spending as a whole.

Universities have benefited enormously from the expansion of higher education, Professor Busemeyer argued, but this growth had reached a point where it could not continue with their traditional missions. “You need further differentiation in the system to blur the boundaries between higher education and VET,” he said.

This has already started to happen in Germany, he explained, where there had been an increase, albeit from a low base, of dual study programmes that combine academic and vocational learning.

In Italy, however, vocational education is still largely limited to schools, said Attilio Oliva, president of TreeLLLe, an Italian education thinktank. Little was on offer from universities, where lecturers held a “snobbish” attitude towards teaching it, he said.

After pressure from industrialists, in the past three to four years, Italy had established a number of technical institutes offering two-year courses, but they remained not well known and still taught only a few thousand students, he said.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login