Figures pointing to UK school-leavers being “markedly less successful” in gaining a university place this year suggest that the economics of undergraduate education could be “beginning to unravel” for some English institutions, an admissions expert has warned.

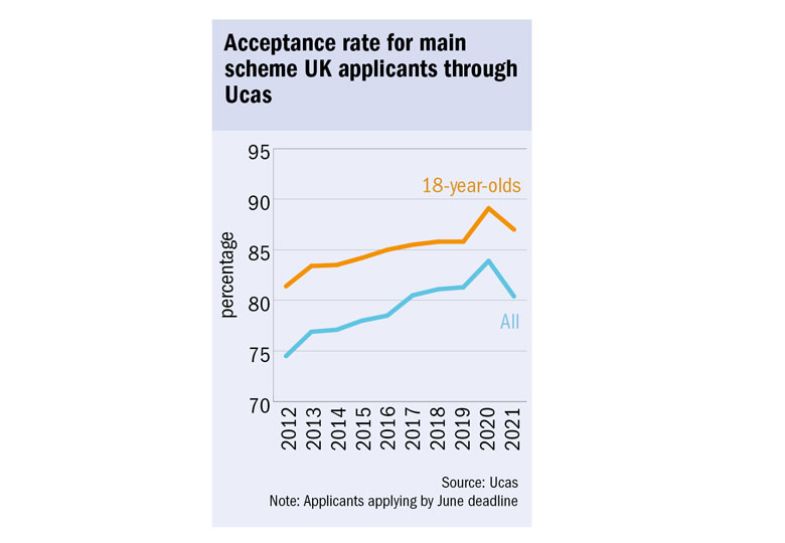

End of-cycle statistics published by Ucas showed that although record numbers of students with offers achieved their first-choice university this year, the share of applicants gaining a place fell from 84 per cent to 80 per cent.

This was the first fall in this measure, known as the acceptance rate, since at least 2012, according to the data, and is the lowest share of applicants gaining a place since 2017.

Mark Corver, co-founder of consultancy dataHE and former director of analysis and research at Ucas, said that places on nursing courses failing to keep pace with a surge in demand did explain part of the fall but this was “not the whole story”.

He said this could be seen from looking at data for 18-year-olds, who are less likely to be nursing applicants, and among whom the acceptance rate still fell for the first time since at least 2012, from 89 per cent to 87 per cent.

Despite this still being higher than 2019, the fall was a “large one” in the context of school-leavers getting record-high grades this year, Dr Corver said.

“This cohort, which had extensive disruption to their education and no exams, were markedly less successful in gaining a place than the 2020 cohort,” he said.

He thought this was most probably linked to a limit on the supply of places meeting rising “aggregate demand” for university.

The 18-year-old population is now on an upward trajectory while an increasing share of this age group is also applying to university, something that policy watchers have been warning will lead to tens of thousands more undergraduate places being needed by 2030.

Dr Corver added that the pandemic was also feeding the short-term rise in aggregate demand by not only leading to higher school-leaving grades but “curtailing alternatives” for young people in the economy. On the supply side, meanwhile, many universities were already dealing with a huge cohort entering in 2020.

“Many universities took in a lot of extra students last year and real capacity constraints, including in accommodation, were an issue in places,” he said.

But he said that another factor hitting the acceptance rate was “probably that the economics of full-time UK undergraduate [education] is beginning to unravel for some universities” due to maximum fees in England hardly rising in a decade.

“The real value of…tuition fees is now down around 20 per cent on 2012. This reduces the ability and desire of universities to increase their UK intake to meet demand; an invisible economic cap rather than a visible student number control,” Dr Corver said.

“The ready supply of places from universities has been taken for granted by policymakers in England for a decade. With growing young demand and unfavourable economics that period may be ending.”

Dr Corver has already warned that such constraints could particularly hit disadvantaged students trying to access the most selective universities. The Ucas data show that the share of all applicants gaining an offer to such institutions fell below 70 per cent this year for the first time since 2013.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login