The UK government’s decision to increase the loan repayment threshold for graduates of English universities is a “significant giveaway” that will cost taxpayers more than £2.3 billion a year in the long run, a new analysis has estimated.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, the raising of the salary threshold at which graduates start to repay loans from £21,000 to £25,000 will also hike the level of public subsidy for the system from 31 per cent to 45 per cent.

The analysis of the policy change, announced by Prime Minister Theresa May at the Conservative Party conference in Manchester, comes in a briefing note from IFS published on 3 October.

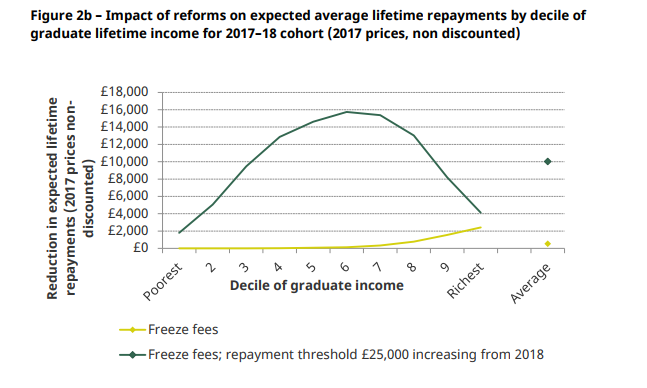

“This is a significant giveaway, largely to middle-earning graduates, who are likely to repay around £15,700 less over their careers, at a long-run cost to government of £2.3 billion per year in 2017 prices,” the note says.

It adds that the change also increases the proportion of graduates who are unlikely to repay their loans in full – due to any remaining debt being written off after 30 years – to 83 per cent, a rise of six percentage points.

Meanwhile, the resource and accounting budgeting (RAB) charge – the proportion of student loans the government does not expect to be repaid and therefore the public subsidy for the system – will go up 14 percentage points over the long term.

Most of the estimates from the IFS on the impact of the changes are long term as the full effect only hits the public finances as graduates near the end of the 30-year repayment period.

The IFS note says that the lowest earning 40 per cent of graduates who went to university since 2012 – when fees were increased to £9,000 – will now be better off than they would have been under the pre-2012 system, when fees were lower.

This is because the new higher repayment threshold only applies for post-2012 loans, so despite having bigger debts overall, low-earning graduates under the current system will make smaller repayments.

As part of the policy announcement, the government also said it would freeze fee levels at £9,250, something the IFS says “has little impact in the short-term, but has potentially significant implications if kept in place in the long-run”.

The note says the freeze would reduce the debt on graduation of the next cohort of students taking three-year degrees by just £800 and save the government £300 million. Only the very highest-earning graduates would benefit, it adds, as most do not repay their loans in full.

It warns that if the freeze continues beyond 2018-19 then it will begin to cause universities major funding uncertainty, given that they had expected to be able to raise fees as part of plans for the teaching excellence framework.

“Freezing the level of tuition fees in cash terms creates uncertainty about the future level of university funding and the implementation of the [TEF],” says the note, by IFS research economists Chris Belfield, Jack Britton and Laura van der Erve.

“This continues a historical trend in university funding noted in previous IFS research, that higher education funding per pupil has consistently been characterised by gradual real-terms falls over a number of years punctuated periodically by relatively sharp increases following large-scale reforms.

“This is not a sensible path for university funding, not least because it makes it difficult for universities to plan effectively for the future.”

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login