Yes, you who must leave everything that you cannot control

It begins with your family, but soon it comes around to your soul

(Sisters of Mercy, 1967)

Notwithstanding the many activities that I shared with Leonard Cohen while growing up with him in Montreal, I would not claim exceptional knowledge of him. Nor would my personal or professional thoughts about his words, music and performance, while strongly held, add anything really useful to opinion already on the record. Leonard’s achievement has been explored, especially since his death a year ago, in countless column inches of impassioned detail.

Absent, however, from the many accounts with which I am familiar is an element that practically shouts out to be acknowledged. Context is the missing piece: the particular circumstances within which Leonard came into this world, and was educated and nurtured. After all, on the age-old question of whether history makes people or people make history, sufficient evidence exists of the former being closer to the truth. As former UK prime minister Harold “Supermac” Macmillan is claimed to have replied when asked what blows governments off course, it’s a matter of “events, dear boy, events”.

The tale worth telling here is one of a superficially stable community whose latent hostilities, in the home as well as beyond, would inexorably, if subconsciously, help shape Leonard’s outlook on life and art. McGill University, which both Leonard and I attended, assumed a vital role in this.

We matriculated and as suddenly – so it seems in retrospect – we graduated. But what happened between remains important. We were sufficiently close to call each other friend, his extended family often the subject of sociable conversation around my family table. We attended some of the same fraternities, where opinion, customarily well fuelled with drink, was shared among like-minded souls (Leonard eventually became president of the debating union). We partied together and – with Leonard comfortably outpacing me – chased the same girls. From time to time, our pursuits were interrupted by an ankle twisted or a leg broken on the nearby ski slopes of the picturesque Laurentian Mountains.

In general at McGill, classes, seminars and term papers were endured with occasional enthusiasm, and it was a rare son or daughter who would attend en famille much – indeed, any – of Montreal’s envied cultural offerings. It would be generous to speak of our condition as naive, or to suggest that we were well prepared for the realities of a callous world all too soon in the offing.

Emblematic of that world was the unforgettable day in September 1959 – by which time Leonard had returned to Montreal after a year in the graduate school of Columbia University in New York City – when the death was announced of Maurice Duplessis, Quebec’s doctrinaire and long-serving premier. I well recall the sheer euphoria with which we all greeted the news. Even within the province’s most parochial circles, the potential for change after an era that later became known as La Grande Noirceur (The Great Darkness) will have been impossible to ignore, conceivably even welcomed. It was a historic day, an explosion of suppressed resentments, whose revolutionary impact will have concentrated the attention of a 24-year-old who, at McGill, had won prizes for his poetry, and saw writing as his vocation.

I lift my voice and pray

May the lights in The Land of Plenty

Shine on the truth some day

(The Land of Plenty, 2001)

Light of a kind did indeed promptly penetrate a crack in the region’s prevailing scheme of things. Here was demonstrable local evidence of that universal wisdom that Leonard would borrow from First Nations. If revolution could reasonably be said to possess a soul, to paraphrase the Russian Marxist revolutionary Lunacharsky, then art could be claimed to be its mouthpiece.

Both Leonard and I were more or less typical products of the Jewish Diaspora. The streets of Montreal, where we were both born, were not quite paved with gold, but, for newcomers, the city was a North American destination of choice. Part of the explanation was its volatile blend of French and Scottish settlers, a chemistry that helped to shape Canada’s most culturally diverse, creative and exciting community.

Sadly, it was also Canada’s most belligerent and adversarial community. Montreal had always been deeply conflicted at multiple levels of race and ethnicity, with consequences for those whose antecedents had escaped the singular ordeals of European life. That something of that particular history awaited our immigrant families in the “bright and shining new world” was inconceivable to them. And yet it did.

What possible justification could a schoolteacher use to greet his incoming class with the command that Jews were immediately to stand, the easier to be identified? How could a school district possibly be permitted to embargo Jewish students altogether? How could McGill, the nation’s international university, justify imposing multiple restrictions on its first-year intake of them? Shamefully, considering the shocking news broadcast daily about Nazified Europe, it was all true.

Parochialism in the wider province was, if anything, even more manifest. The gulf evoked the two Frances of Quebec’s colonial origins – the rural, “real” France favoured by Duplessis, and the secular France légale – and the tensions that played themselves out across the land in classrooms, boardrooms and around the family hearth – and too often violently on its streets, as I myself, utterly panic-stricken, would on separate occasions experience. France’s recent national elections, highlighted by the confrontation between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, prove that we exist in history’s shadow.

For those of Montreal’s Jews with memories, there has also been an all-too-familiar ring to reports of – as The New York Times put it earlier this year – “the [media’s] trivialisation of anti-Muslim crime and the outright demonization of Muslims [that] contribute to a poisonous political climate across Quebec”. It is an image at odds with Canada’s lofty 150th birthday message, broadcast far and wide this year by its progressive new prime minister, Justin Trudeau.

How, then, to cope with this indiscriminate prejudice, if not to foil one’s apparent fate? There were options. One was splendidly encapsulated by another of Leonard’s friends, Bernard Shapiro, whom I interviewed for The Times and BBC Radio 4 in 1994: “We just got on with it.” The occasion was Shapiro’s instalment as the first Jewish principal of McGill, an international event given the campus’ long tradition of anti-Semitism.

Leonard’s choice was the more calculated. He escaped, finally making, in 1967, for the American frontier and the warmer welcome that was thought always to be on tap there, and that he is said to have experienced while at Columbia. As Sylvie Simmons writes in her 2012 biography, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen: “The big reason for [Leonard’s] going to New York was to get away from Montreal, to put space between himself and the life his upper class Montreal Jewish background [had] mapped out for him.”

I’m sentimental,

if you know what I mean;

I love the country but

I can’t stand the scene

(Democracy, 1992)

“Go south, young man” was a conventional frame of mind in those times. And in going, Leonard berated Canada’s Jewish community, in which, as he put it, “honour had migrated from the scholar to the manufacturer, where it hardened into arrogant self-defence”. It was, Leonard said, a culture “[with] nothing but contempt for the poor and learned...scruffy immigrants with no possessions and the smell of failure. What such a wicked community needed”, he argued, “was not a priest but a prophet.” That statement was clearly an evocation of the Duplessis legacy.

Leonard’s Montreal “was all about division and separation [where] the Jews and Protestants had been piled together on the simple grounds of being neither French nor Catholic...and where the only French in [the Montreal subdivision of] Westmount were the domestic help”.

Westmount’s Jews were a close-knit and socially prominent minority in a wealthy English Protestant neighbourhood. The latter was itself a minority, albeit a powerful one, in a city and province overwhelmingly Catholic French: themselves a minority in Canada. “Everybody felt like some kind of outsider”, Leonard lamented. “Everybody felt like they belonged to something important. It was a romantic, conspiratorial, mental environment, a place of blood, soil, and destiny.”

If you are the dealer,

let me out of the game

If you are the healer,

I’m broken and lame

If thine is the glory,

mine must be the shame

(You Want it Darker, 2016)

Not to be outdone were the considerable numbers choosing education at the Jewish day schools, isolated from the monolithic Protestant and Catholic systems, themselves mutually isolated. All of which ordained a ghettoised society on a grand scale. It was as if a culture had been designed expressly to breed ignorance, suspicion, hostility and ultimately fear.

Mention isolation, however, and it would be inexcusable to ignore the Mohawk Indians of the First Nations, especially the community’s attitudes and behaviour towards them. Inured to unemployment, poverty and disease, they existed on a reservation, an officially sanctioned form of detention on Montreal’s outskirts, out of sight and literally out of mind. Nor may it be assumed that such history has been consigned to the past. As recently as two years ago, Payam Akhavan, a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague and professor of law at McGill, told an audience at the Canadian High Commission in London that “Canada’s stubborn indifference to the plight of indigenous peoples is so entrenched that their shameful situation has become increasingly accepted as a normal condition, rather than a national crisis requiring urgent action.” This amounts to every Canadian’s claim to original sin.

McGill’s setting epitomised the heart and soul of the unloved British presence in Montreal. Its anglicised campus was, at least until Duplessis’ death, a conspicuous reminder to the francophone majority of its subservient “other” status in the scheme of things, dating back at least to 1759 and a momentous military defeat of the French by the British at Quebec City.

Seldom since then had successive anglophone generations been short of pretexts to reinforce their inherited power to compromise the rights of others where convenient. Hence their wholesale claim to positions of authority in manufacturing, finance, transportation, publishing and the media. If French-speaking, unless doctor or priest, you were labouring class. Even the city’s architecture, evoking Scotland, was an inescapable reminder of the natural order of things.

Si tu vois mon pays,

(If you see my country)

Mon pays malheureux,

(My unhappy country)

Va dire à mes amis

(Go and tell my friends)

Que je me souviens d’eux.

(That I remember them)

(Un Canadien Errant [The Lost Canadian], 1979)

This promise of abundant opportunities in business, professions and the trades for English speakers – albeit Jewish ones – such as Leonard and me helped cloud one’s awareness and mitigate the everyday effects of prevailing bigotries. The world in which we grew up certainly wasn’t all gloom.

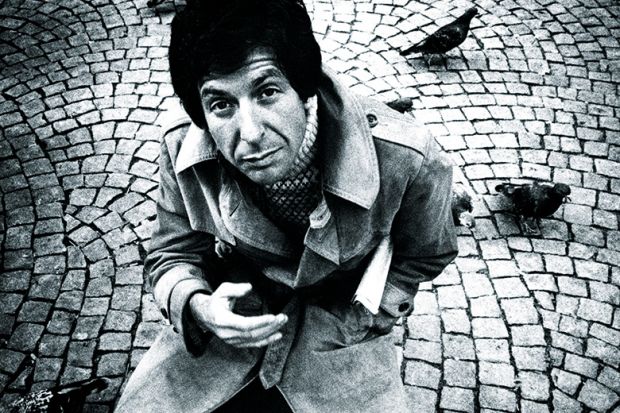

Still, an abiding image persists of Leonard at McGill: a solitary figure after class, slipping through the campus gates with his guitar slung across his back. He was heading towards life beyond the lecture hall, putting behind him a world that defied easy expression. A nearby cafe was his objective, a student hangout. Here, he would find his dissident voice, his back already turned to “everything that you cannot control”, the default philosophy of his life.

I heard the snake was baffled by his sin

He shed his scales to find the snake within

But born again is born without a skin

The poison enters into everything.

(Treaty , 2016)

Kenneth Asch is a freelance journalist. He is also director of the self-conceived Peace and Commemoration project at the University of Oxford, which examines the modern relevance of ancient Greek tragedy through words and music. It is due to be launched at the University of Helsinki next spring, before touring the Europaeum network of universities.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login