Laura (not her real name) is a lecturer at the University of Oxford. Her salary is more than 60 per cent higher than the UK average, and she describes her academic position as a “dream job”. But she fears that she may have no choice but to leave.

Stroll down Oxford’s historic high street, glance in the window of an estate agent, and it becomes obvious why. According to the website Rightmove, the average house price in Oxford is now just under £470,000: more than 10 times Laura’s salary.

Laura and her partner do not have a large enough combined income to afford a house in the city even though they have saved up a “pretty respectable” deposit. Instead, they rent a house for an “extortionate” £1,300 a month. Nor is the prospect of home ownership even on the horizon. The price of houses on Laura’s street have been going up “exponentially” in recent years, and sports cars have begun appearing outside them – perhaps owned by commuters with lucrative London jobs, she suggests.

“I’ve never earned more in my life, but I’ve never felt so poor,” she says. “If we choose to stay here, we are still really hurting ourselves financially, which is sad.”

Oxford has been described as the UK’s most unaffordable city; the gulf between house prices and average incomes there is even bigger than it is in London. Bob Price, the city’s Labour council leader, warns that “if things carry on…we are very much in danger of not having Oxford in the top four or five universities in the world”.

Oxford’s plight is by no means unique. If you are an academic attempting to buy a house in, say, San Francisco, New York, Sydney or Hong Kong, Laura’s plight might well sound frustratingly familiar. Spiralling real estate values in many of the world’s top university cities are causing major headaches for institutions trying to recruit and retain top scholars. Some institutions are even being forced to plough tens of millions of dollars into temporary accommodation, affordable housing and loan programmes for academics.

Yet, as data compiled by Times Higher Education show (see below), the pain is not spread equally – and, in a globalised market for top academics and the prestige they bring, this could create major winners and losers.

In Price’s view, Oxford is losing out badly. Many of the star overseas professors whom the university wants to attract are “used to a certain lifestyle” and expect to be able to live in the city centre. But even if offered a salary of, say, £100,000 (the average professorial salary at the University of Oxford is £67,224), they find that the cheapest house they would settle for costs 10 times this.

The days when professors could realistically afford to buy a detached house in leafy North Oxford are all but gone. On the street where J. R. R. Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings, all but one of the homes sold in the past decade have gone for more than £1 million – and some for substantially more.

“As a consequence, academics don’t live in Oxford; they live outside – which sounds OK, but then you have the consequential problem of people commuting in,” Price says. Nearly 50,000 people attempt to travel into the small, congested city every day, he explains, and university parking spaces are limited.

Until the end of 2013, Price was director of human resources at the city of Oxford’s other higher education institution, Oxford Brookes University. When recruiting new academics or administrators, at “pretty much every senior position…at least one dropped out from the shortlist” because of housing costs, he says. For one senior post, the original shortlist of half a dozen dwindled to just one candidate, “overwhelmingly” because of the unaffordability of housing, the dropouts told him.

By contrast, Alistair Fitt, the new vicechancellor of Oxford Brookes, points out that academics often do not explain their reasons for withdrawing from shortlists. So although the cost of housing in Oxford is “undoubtedly a major issue”, he says that he has not seen “any really hard evidence” that it results in a “significant number of candidates dropping out”.

At the University of Oxford, however, senior managers are candid about the problem. “Every time we recruit somebody, we have a headache making sure they can afford a house equivalent to the one they are [currently] in,” says John Bell, Regius professor of medicine at Oxford, who shares responsibility for recruiting senior scholars to Oxford’s medical science division. “That gets to be quite hard.”

But, says William James, pro vice-chancellor for planning and resources at Oxford, it is early career contract research staff who are worst affected by the issue. “Anxiety about unaffordable rents and the unsuitability of cheap rooms is good neither for them nor for their research,” he observes.

The issue extends much further up the career ladder. Laura has a permanent contract and is well beyond the early career stage. But she says that quitting Oxford for another university because of housing costs is “a common topic of discussion among young academics” there. Some scholars pining for a roof of their own are even considering quitting academia altogether. Sarah (not her real name) is a social sciences research manager and PhD student at the University of Cambridge, where, according to Rightmove, average house prices are just as high as they are in Oxford (although the city is generally agreed to have a better variety of nearby commuter towns and the average professorial salary is higher, at £81,096). Even though her husband brings in a “considerable” private sector salary, “at the moment there’s absolutely no way we could buy anywhere near Cambridge”, she says – adding that many of her academic contemporaries are in a similar position. If she and her partner cannot find a way to save up a mortgage deposit, Sarah says that she will look for a different job entirely.

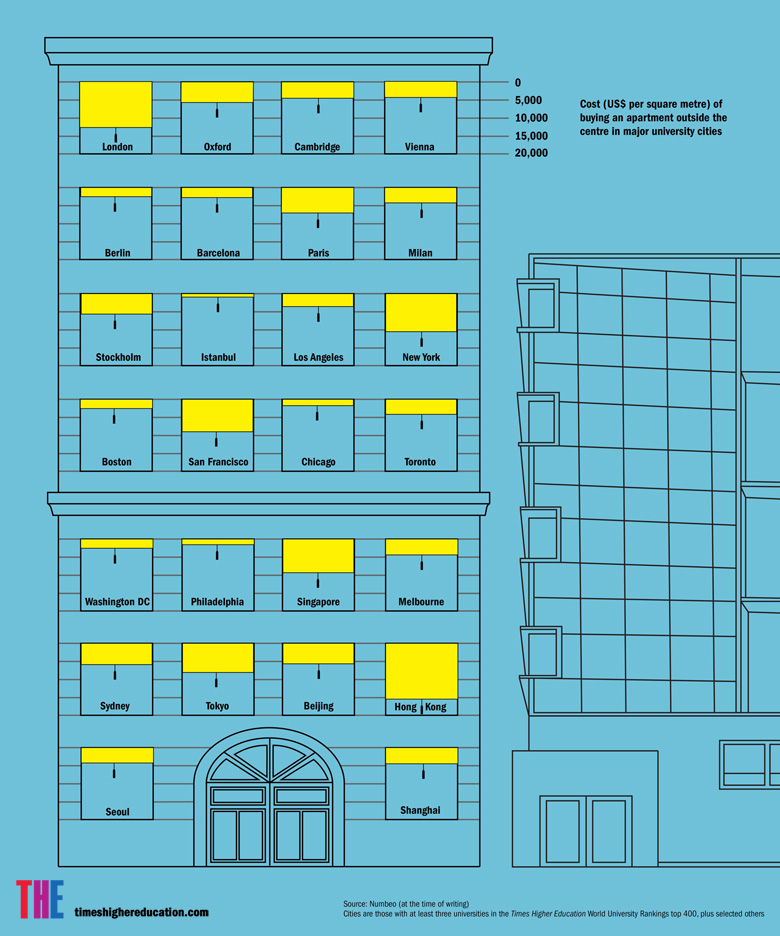

The cost of buying an apartment in major university cities

“Something has to give because Cambridge can compete on its reputation for only so long,” she says.

London, of course, is the starting point for all conversations about ludicrous property prices in the UK. It is home to 23 universities, as well as more than a dozen branch campuses, specialist institutes and colleges. It has more universities ranked in the top 400 of THE’s World University Rankings than any other city in the world. And, according to the website Numbeo, it is the second most expensive university city in the world in which to buy a square metre of property (see above).

Not surprisingly, then, university leaders there are feeling the effects. “We do know that we have to offer pay at the higher ends of pay bands, or, for senior roles, we have to offer more attractive packages,” says Julius Weinberg, vice-chancellor of Kingston University. “This is particularly true in attracting staff from outside the South East [of England] and abroad.

“We also have concerns about the retention of younger staff, as they will often seek roles outside London when wanting to start a family or have more space,” he adds.

Echoing the point that the high cost of housing in the capital is “particularly challenging” for early career staff, Evelyn Welch, vice-principal for arts and sciences at King’s College London, suggests that the taxpayer might need to step in. “We welcome any opportunity and government support that will ensure we are able to attract and retain world-class academic talent in a city like London,” she says.

It is almost impossible to quantify the scale of the recruitment problem because universities cannot know exactly who has been put off from applying for their jobs by housing costs. Weinberg acknowledges that there is “anecdotal evidence” that Kingston’s pool of candidates is reduced because applicants are deterred by housing costs, but Oxford’s Bell says that although his division “may lose a few” senior candidates to other universities, he does not think that the number is very large because the lure of working with the best will always draw people to Oxford. “I don’t honestly think house prices are going to change that dynamic,” he says.

When recruiting, “you can usually never really match a North American salary. The houses [there] tend to be very big…and cheap. But then again, people are prepared to…make a sacrifice to come to Oxford,” he adds.

Price disagrees, however. Oxford has achieved its current reputation, he points out, because top academics are attracted by the prospect of working with other talented minds in a “virtuous circle” of success. But “if you start to lose that because person X goes from Oxford to Berkeley” because of unaffordable housing, this leads to a “vicious circle” of people leaving the university.

London is much bigger and better connected than Oxford, and some believe that its myriad cultural attractions help to make up for its high living costs. Sir Paul Nurse, chief executive of the Crick Institute, London’s new biomedical “superlab”, has said that for younger researchers “the attractions of one of the greatest cities in the world…will compensate for not living in the largest flat that they could do if they lived somewhere else”. James Stirling, provost of Imperial College London (average professorial salary: £91,176), also sees the “‘added value’ benefits of living and working in a global city” as something that lures academics in – adding that “London and its surrounding commuter areas [provide] a significant amount of diversity in terms of housing options available”.

Yet unaffordable housing can undermine some of the services that academics take for granted. In October last year, the BBC reported that Oxford’s housing costs meant that the city was facing “catastrophe” because it was unable to attract bus drivers, nurses and teachers. Similar warnings are being made about London – not least with regard to students. Last November, the London Assembly’s housing committee warned that those from “ordinary families” risk being priced out of the capital, where average weekly student rents reached nearly £160 a week in 2012‑13: a rise of 26 per cent in three years.

Scholars in many other university cities will recognise these problems. San Francisco’s tech boom has been blamed for driving teachers out of the area and lowering the quality of local schools. In Hong Kong, the price of houses – or, more accurately, apartments – dominates newspaper headlines almost as much as it does in the UK. As it is spread across a peninsula and numerous islands, the city has little room to expand, and it is the only city pricier per square metre than London (see graphic, above).

This is a worry for Tony Chan, president of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Asked if housing costs are a threat to recruitment, he says: “I think we are heading towards that crisis.” HKUST has about 500 apartments on campus for academics and senior support staff, which they are able to rent for 10 per cent of their income. This is very cheap by Hong Kong standards, but, as Chan points out, the disadvantage is that academics cannot build equity in their own property.

To ameliorate its housing problems, the institution has divided some apartments in two. But after a switch from three- to four-year degrees, the university has had to increase the number of faculty by a third. “We are still in the process of recruiting,” Chan says. “So at some point, we are going to run out of apartments, and then we have a problem.”

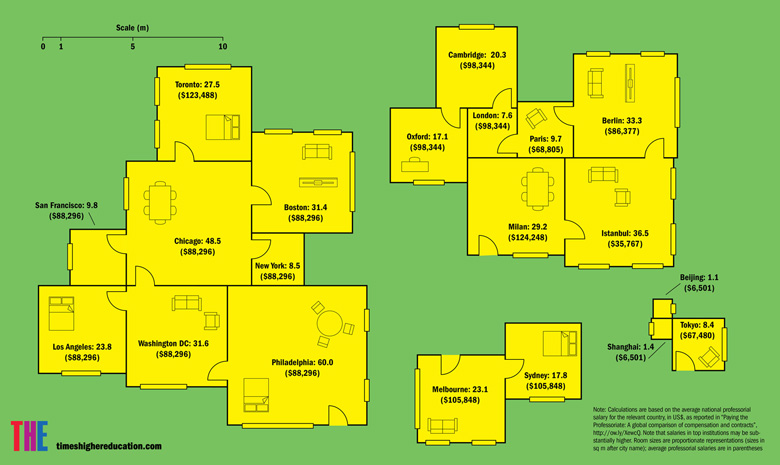

How many square metres per year can you buy with a professorial salary?

In the US, institutions in property hotspots face comparable problems. A spokeswoman for Stanford – where academics have to compete with tech industry millionaires for a home in Palo Alto – acknowledges that the university is “located in one of the costliest housing markets in the US”. And the high cost of Bay Area housing is cited in Stanford’s latest annual financial accounts as one of the future “challenges” facing the university.

But Stanford, where the average professorial salary is $210,339 (£146,508), assists its staff in several ways. Faculty are offered interest-only loans to buy houses, and the university has built a 900-home “faculty neighbourhood” on campus. By the end of 2018, it will have added 180 more homes in a new “University Terrace” development next to its research park. These houses are sold to faculty, and any price rises are fixed by the university, preventing departing academics from cashing in by selling them on the open market.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the continent in Boston, Harvard University has taken on a role more usually reserved for city authorities. In the decade from 2000, it lent about $20 million (£13.6 million) to finance the purchase and refurbishment of affordable accommodation. But these developments are not built specifically for academics: they include homeless shelters and workspaces for artists, as well as homes for first-time buyers. Harvard does also own 66 properties in Cambridge and Boston that it rents out to graduates and faculty. A spokeswoman says that the university has the capacity to house nearly half of postgraduates in its own buildings. However, rents are set at market rates – the cheapest available costs $1,140 a month for a single bedroom.

UK universities are beginning to turn to similar solutions. Cambridge has a shared equity scheme to help new academics purchase a house, contributing up to £300,000 to buy a property in tandem with the academic. Faculty using the scheme must pay 2 per cent interest a year on the university’s contribution.

The university’s new North West Cambridge Development will, from this summer, provide rental accommodation for 1,500 staff from the university and other linked research organisations “who cannot afford open-market rent”. But the development’s website admits that the university “is unlikely to be able to meet all of its need for [university] key worker housing at the…development”. Priority will be given to research postdocs, a spokesman said. But more broadly, “building new and affordable houses is…vital to the economic health of the region”.

Dusty Amroliwala, deputy vice-chancellor and chief operating officer at the University of East London, is considering whether an apartment block in new student accommodation should be set aside for university staff in their first two or three years of employment to allow them to “find their feet” in the capital. The Crick Institute is toying with a similar idea. The problem is that academics who end up relying on their universities for housing become like a “vicar in a tithed house”, says Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder professor of geography at Oxford and a prolific writer on housing problems in the UK.

In other words, faculty become overly tied to their institution. This might sound attractive to a particularly cynical university manager, but Dorling argues that “you would actually want somebody who is unhappy in their job to leave”.

Living in the same complex as students brings its own irritations. One of the reasons Dorling left the University of Bristol early in his career was that “the undergraduates could outbid me [in rental costs], and were always in the flat above me. If you can’t get away from students at night, as well as during the day, that’s not good.”

At the National University of Singapore – where, as in Hong Kong, space constraints have pushed up housing costs – staff are offered either subsidised housing or an allowance to compensate for the cost of renting privately.

The latter option is something that UK universities may have to start looking into, says John Raftery, vice-chancellor of London Metropolitan University. But he admits that his own institution “couldn’t afford” to do so.

While Dorling acknowledges that there are spots in the US where houses are even less affordable than they are in Oxford, he argues that the UK is “very, very bad compared with Europe”. He makes the simple point that as a university seeking to hire staff “you would want to be in the position that anyone from anywhere can come to a post if they are good” without having to worry about housing, but he does not see that scenario becoming closer to reality any time soon in the UK.

“People often make the mistake of thinking it’s so bad it can’t get worse. But we don’t have signs of the prices slowing down,” he says.

According to Oxford’s Bell, that “many of the best universities sit in a place where the house prices are crazy” is, to some extent, inevitable. “Universities drive economic growth”, which in turn drives up prices.

But his confidence that Oxford’s academic pulling power will save it from being outstripped by high-quality institutions in cheaper cities such as Chicago and Berlin may be shaken by the thinking of academics such as Laura, who is seriously contemplating moving to the US.

Quitting Oxford would not be an easy choice for her and her partner because “when you get a job [at Oxford] you think, ‘I’ve done it!’” But then “the novelty wears off”, she says, adding that she feels like “a cog in somebody else’s investment”. She would rather not have to leave, but the reality is that “the situation in Oxford is making that decision for us”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The housing block

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login