Hong Kong’s campuses are some of the most international and liberal-minded in Asia. They serve as an important platform for debate about the fate of freedoms and democracy in the former British colony under Chinese rule. However, as increasingly violent anti-government protests continue into their fifth month, with little signs of abating, the territory’s universities have found themselves in a seemingly impossible position.

The critical nature of Hong Kong’s students and academics has made universities a target for mass protests, clashes and vandalism, as well as criticism from pro-government voices. This came to a head this week, as violent clashes between protestors and police led to the use of use of tear gas on university grounds for the first time during the protests and to the closure of nine public and two private universities for several days. Hong Kong's Vocational Training Council also suspended classes at its 13 tertiary education centres after one of its students was shot by police in a residential area. Subsequently, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, where students responded to police tear gas and rubber bullets on Tuesday by throwing bricks and setting up burning roadblocks, announced a suspension of classes for the entire semester.

Administrators are caught between keeping the peace on their campuses and standing up for the rights of their students as they clash with the authorities in the wider city. Universities are also tasked with defending the academic freedoms of their scholars, many of whom have openly criticised the Hong Kong government at a time of unprecedented backlash against the authorities.

Hundreds of students have been arrested in connection with the protests since they began in June, in response to the Hong Kong government’s intention to implement an extradition treaty with mainland China that would have allowed Hong Kong to commit its citizens – including critical political figures – to mainland China’s much less politically independent judicial system.

In some of the more extreme cases, universities have warned police to stay off their campuses. Academics have rushed to police stations to secure the release of their students. And one University of Hong Kong (HKU) student leader even fled the territory for safety reasons, as the protests grew in size and intensity amid a widespread feeling that the extradition bill was emblematic of a gradual erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomy and civil liberties.

By the time the bill was officially withdrawn in the Legislative Council on 23 October, Hong Kong had endured 20 weeks of civil unrest. Students’ involvement in the protests culminated in a two-week strike at the beginning of the academic year, and, from 9 June to 17 October, nearly 900 students, both secondary and tertiary, were arrested in relation to the protests, the Hong Kong Police tell THE. That number is continuing to rise ahead of contentious district elections this month, as government tactics become more aggressive.

After five HKU students were arrested this week within 24 hours, HKU president Xiang Zhang appealed to the police to “ensure the safety of the detained students and to observe fully their fundamental rights”. In an email to the university community, he added: “We understand that these are times when emotions are running high everywhere. We are also very saddened to see the casualties and loss of life arising from the protests. Let us remember that this is our campus, where we study and work, and we should safeguard it.”

Previously, on 1 November, a small group of angry students had descended on Zhang's personal residence, demanding that he respond to their ultimatum to condemn police brutality, forbid police searches on campus, provide concrete aid to arrested students and hold a forum with students. Zhang emailed students that day agreeing to the forum and calling HKU “a citadel of freedom and knowledge, where we cherish civil and rational debate, and seek to find solutions with knowledge, wisdom and imagination”. He acknowledged that “I know many of you are in pain, Hong Kong is in pain”, adding that “none of you needs to issue an ultimatum to talk to me”.

Three days later, for the second time in two months, staff from Hong Kong Baptist University were called to a police station to aid an arrested student journalist, and a vice-president at Shue Yan University visited a hospitalised student who had reportedly been hit by a tear gas canister while volunteering to provide first aid.

Meanwhile, Wei Shyy, president of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, visited a hospitalised student who allegedly suffered a brain injury while trying to escape police tear gassing earlier this month. On Shyy’s return to campus, he was surrounded for five hours by furious students demanding that he take a stronger stance against the police. The student died that week, and Shyy was seen weeping during a graduation ceremony, as he called for a moment of silence for the young man.

If and when peace returns, this city of 7 million people will never be the same again. About 40 overseas states have issued travel advice or alerts about Hong Kong; the city’s famously efficient subway system has suffered vandalism to 90 per cent of stations; and its economy has entered what is known as a technical recession: two consecutive quarters of declining GDP. Tear gassing, considered a rare and extreme measure when used during the previous pro-democracy movement, Occupy Central, five years ago, is now so common that it has been used in almost all 18 of the territory’s districts, along with rubber bullets and water cannon.

Anthony Cheung, research chair professor of public administration at the Education University of Hong Kong and a former minister in the Hong Kong government, told a political science conference at HKBU in late October that university leaders must “stand firm to maintain university campuses where people can really speak – only then can you really have dialogue”. But when passions are so high, free speech and dialogue can quickly turn ugly.

The heads of the main universities in Hong Kong have met with students and penned numerous statements denouncing violence and calling for calm. In a rare show of solidarity, the chairs of council of all eight public universities issued a joint statement reinforcing that “all members in university communities are expected to uphold free speech and to respect the views held by all other members of the community. In this sense, universities cherish a diversity of views and promote robust, yet civilized, and respectful discussion of such views. Universities are, however, not battlegrounds for the resolution of political issues and should not be drawn into supporting any particular political position.”

According to Christine Loh, a chief development strategist at HKUST, university managers and academics are facing an “uphill battle” to “absorb the frustration and anger” of the territory’s young people. “Tension exists among students – some students are strong supporters of the protests, while others are not – and tension also exists between local Hong Kong students and students from the mainland,” says Loh, a former Hong Kong lawmaker and former government official.

Universities are also struggling to maintain business as usual in their day-to-day activities. The chaos has enforced a variety of cancellations, from international symposia like the 2019 edX Global Forum, due to have run this week at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, to student inaugurations and open days. Some cross-border exchanges, like those at the HKU and Chinese University of Hong Kong medical schools, have also been put on hold.

Hong Kong’s university system has a high reputation internationally. Its top institution, HKU, ranks 35th in the latest Times Higher Education World University Rankings, and it has another two institutions within the top 60, and five within the top 200.

“Hong Kong has spent many years and resources to build its universities through hiring faculty from around the world and increasing the number of non-local students,” Loh says. “The academic and research achievements of our universities have advanced substantially. The immediate impacts of the current problems will be in non-local student and faculty recruitments. Longer term, there may be impacts on rankings, which, in turn, affect reputations.”

Hong Kong’s education ministry, known as the Education Bureau, plays down the problems and voices its support for the city’s universities: “Despite recent developments, Hong Kong remains a safe, open and vibrant international city as well as an education hub,” it says, in a statement to THE. “Since the commencement of the new academic year in September, teaching and research activities at our local universities have been orderly, while universities continue to strive for academic and research excellence. The government will continue to work closely with the higher education sector to promote internationalisation and to further enhance the quality of higher education in Hong Kong.”

Still, there are signs of strain in the relationship between universities and the government. Hong Kong’s embattled chief executive, Carrie Lam, is the ex officio chancellor of all of the territory’s public universities, but she will skip her usual appearances at autumn graduation ceremonies. This decision was announced after some students began donning face masks to receive their diplomas: a symbol of their defiance of the ban on such masks that Lam enacted, using emergency legislation, in October.

Of all the university chiefs, the most outspoken on behalf of his students has been Rocky Tuan, vice-chancellor of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), who has called for an investigation into student arrests and related police violence. Following an October meeting attended by more than 1,000 students, at which he heard testaments about alleged police mistreatment, including sexual harassment, the former University of Pittsburgh senior manager issued a statement that was striking for its emotional openness. “My heart is heavy and unsettled as I pen this personal letter,” he wrote. “I heard loud and clear every word uttered by our students, which brought me no small share of sadness and regret.”

During his first protests-related meeting with students in late July, Tuan had stressed that although he could not use “public expenses” to pay the legal fees of CUHK students facing criminal charges for their role in the protests, the university would “align” such students with “those who have offered legal aids”. Unimpressed students reacted by covering his car with sheets of paper and sticky notes, condemning his responses during the meeting as inadequate. His October statement, by contrast, was received positively by students, who presented him with a large banner of appreciation.

However, the statement also drew an immediate backlash from powerful pro-government forces, such as Chinese state newspaper The People’s Daily, Lam’s predecessor as Hong Kong chief executive Leung Chun-ying and all four of the territory’s police associations.

University-linked groups, for their part, have used strong language to voice their displeasure with the government and its head. HKU Convocation, a statutory body that comprises graduates and teachers of the university, passed a vote by a large majority to ask Lam to step down as chancellor of HKU, her alma mater, for “having caused unforgivable havoc to Hong Kong”.

Such moves have not so far led to any political threats to universities’ funding, but it is notable that all of Hong Kong’s main universities are public and rely on HK$20 billion (£2 billion) in annual government grants for more than half their budgets. Without it, they would be forced to raise undergraduate tuition fees far above their current HK$43,100 (£4,265) figure: perhaps to the figure three times higher that is already charged to non-local students, including those from mainland China.

Moreover, the Chinese government is also an important source of research grants and other donations to Hong Kong universities. For example, HKUST recently received HK$45 million from various sources in mainland China. The institution is also building a new branch campus in Guangzhou, on the other side of the border.

Another potential threat arising from the protests is a decline of non-local students coming to Hong Kong. This is likely to be a particular cause of anxiety given Hong Kong universities’ high level of internationalisation – which is one of the reasons they rank so highly – and the fact that about 70 per cent of the territory’s non-local students come from the mainland, amounting to about 12,000 out of a total student body of 100,000 at the eight main public universities.

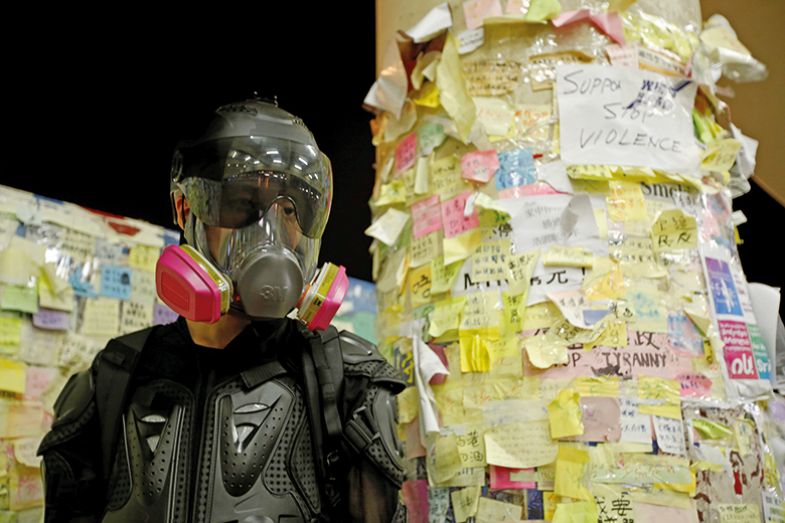

Heightened tensions between Hong Kong and mainland Chinese students have been in evidence at campuses across the world, with clashes between the two groups occurring in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, the US and Taiwan. Most of the conflicts take place at so-called Lennon Walls, which are plastered with colourful sticky notes containing political messages or slogans. Most Hong Kong campuses also have “democracy walls” or “big character walls”, where students can express their personal opinions by posting flyers or other materials. Scuffles happen when some students try to remove materials that they find offensive, but are then accused of censorship by other students.

One problem facing Hong Kong universities is that mixed into well-meaning messages about democracy and freedom are other materials that are offensive, obscene and discriminatory. Some flyers recently seen at HKU rail against “commies” and tell Chinese to “go back to the mainland”. Such messages are potentially intimidating to young people already struggling to adjust to a radically different political culture from that of the mainland.

Sean McMinn, an associate professor of language education at HKUST, meets up with small groups of his students – mostly from Hong Kong, mainland China and other parts of Asia – at a “safe space”, such as the university cafeteria, so they can discuss their personal feelings about the protests with him.

“There are a lot of internal conflicts,” McMinn reports. “They don’t always know what to think, and they may feel pressure from their peers, who are treating this like a black and white issue. If a student expresses another opinion, they may be criticised. So they are afraid of speaking openly, and don’t know who to talk to.”

McMinn teaches digital literacy and has written about the power of social media memes in amplifying political views among youth. “Regardless of my opinion of the government, I don’t like to see unfounded or racist claims. Some of the images are very emotive and reinforce bias. That’s my main concern,” he says.

The protests have prompted universities to institute safeguards against hateful behaviour. In September, the HKU Senate issued a statement adopting a “zero-tolerance” approach to hate speech, identified in accordance with the United Nations’ definition: “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of…their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor”.

One concern, particularly at downtown campuses, is that it is impossible to tell which Lennon Wall contributors or masked protesters are genuine students and which are outsiders. City University learned this after one of its planned meetings with students was disrupted in October. “Surprisingly, before the start of the first session, planned as a civilized dialogue with local undergraduate students, the venue was surrounded by a large number of unidentified people clearly intent on interrupting the session and preventing the dialogue taking place,” wrote Horace Ip, City’s vice-president (student affairs) and Sunny Lee, its vice-president (administration), in a statement issued by the university’s recently established emergency response unit, which they co-chair. “The situation was chaotic and intimidating to staff and those students who wished to attend,” they added.

Indeed, multiple people THE has spoken to testify to having heard students, parents and academics voicing concern about safety in the city. One of them is Education University’s Cheung. “I am not a university administrator, but, personally, I’ve heard that some overseas students – and their parents – are reluctant to come to Hong Kong,” he says. “Every day on TV broadcasts, they see protests, violence, [subway] disruptions – and they don’t know the context or local situation. If the unrest continues for a longer period of time, it could do damage to [academic] exchanges.”

However, while drops in admissions will not be evident until the application process for the 2020-21 academic year wraps up in the spring, universities deny any drop-off in international applications. Both undergraduate and postgraduate interest from beyond the territory “continues to be robust”, according to a spokeswoman for HKU. Some visiting summer students did “express concerns about the situation of class boycotts and protests in the territory”, but there was no major increase in dropout rates from such courses. The same is true of exchange programmes that began in September, she adds.

At CUHK, too, the proportion of mainland students accepting offers is “more or less the same as that of previous years”, a spokeswoman says, and no existing mainland undergraduates have yet withdrawn from studies. “CUHK has striven to create a culturally diverse and inclusive campus to promote mutual understanding among staff and students from different parts of the world,” the spokeswoman adds. “All CUHK members enjoy academic freedom and freedom of expression. The university will continue to uphold and cherish these core values.”

Other universities in the territory echo that commitment to academic freedom, and there has not been a publicly reported case of a professor being removed for critical commentary against the government. Even Benny Tai, the law professor jailed for 16 months for his involvement in the 2014 Occupy Central movement, is still on staff at HKU.

Moreover, academics in the fields of law, politics and journalism have been quick to produce polls and research related to the protests, acting as watchdogs over the government’s actions. For instance, four researchers, all from different Hong Kong universities, conducted 12 onsite surveys during street protests between June and August. Their polling, conducted for CUHK’s Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey, showed that about 80 per cent of demonstrators felt that the protests should continue if the government made no more concessions.

Masato Kajimoto, assistant professor of practice in HKU’s Journalism and Media Studies Centre, has launched a project to fact-check “fake news” about the protests. CUHK is starting a public archive of protest-related materials. And HKBU is planning to act as an independent monitor of the upcoming district elections, on 24 November.

“I’ve always believed that Hong Kong, in terms of academic freedom at universities, has among the best practices in the world,” says the Education University’s Cheung. “Our academics are free to say, research and publish what they want.” But it is clear that any deviation from that state of affairs could affect international academic recruitment.

HKUST’s Loh also acknowledges the possibility that, as well as causing a drop in international student recruitment, the “continuing tensions” on Hong Kong campuses will make it harder for the territory’s universities to hire international staff. “Another concern is that faculty may look to relocate,” she adds.

One academic who moved to Hong Kong in the midst of the crisis is Alistair Cole, who had been a professor at Cardiff University and Sciences Po (Institute of Political Studies) Lyon, before taking the helm at the department of government and international studies at HKBU in September.

The following month, his department hosted the Hong Kong Political Science Association’s annual conference, one of whose speakers was Tanya Chan, a pro-democracy lawmaker who was one of the eight defendants sentenced alongside Tai for their involvement in the Occupy Central movement.

“Hong Kong universities have a strong reputation – and that is something of a safeguard. They are robust institutions,” Cole says. “But they have to be careful to maintain their academic freedom, so they can maintain that reputation.”

Cole says that his university will keep pushing to build its overseas collaborations, in areas such as double-degree programmes. “We are confident that there is still a will and a willingness to come to Hong Kong,” he says.

However, international staff’s inclination to stay the course will not be helped by several instances – albeit isolated – of student protesters lashing out against instructors whom they felt were censorious or not supportive of their cause.

Chan Wai-keung, a lecturer at Hong Kong Community College, an extension of Hong Kong Polytechnic University, was replaced in his teaching duties in early October, after more than 100 student protesters prevented him from leaving the classroom while shouting profanities at him. They were angry about a comment Chan made in a local newspaper calling for tough penalties for breaking the new anti-mask law and for protesting violently.

Meanwhile, Tan Yong Chin, who moved from Singapore to Hong Kong recently to join CUHK, had his office vandalised after he threatened to give students “zero points” for presentations that included “political announcements or statements”, according to an internal email on 18 October, leaked to The South China Morning Post.

Asked if student protests were affecting campus operations, Ray Yep, associate head of the department of public policy at CUHK, admits to “genuine concerns about the recruitment of staff”. And he worries about what the future may hold.

“Hong Kong is a cosmopolitan society, but maintaining that is easier said than done,” Yep says. “We need to draw the line on how to deal with these difficulties.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Walking a diplomatic tightrope.

Note: The version of this article that appears here differs slightly from the print version to reflect events that occurred after the magazine when to press.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login