In 1918, in the dying days of the First World War, a philosophically minded former war secretary and Lord Chancellor by the name of Richard Burdon Haldane chaired a UK government task force called the Machinery of Government Committee. The resulting report recommended that while politicians should have some oversight regarding the general direction of the spending of research funding, decisions on precisely what and who to fund should be left to the scientific community.

At least, that is how the story goes. In fact, the King’s College London historian David Edgerton points out that the so-called Haldane Principle was not actually mentioned in the report. Something resembling the modern understanding of the principle was misattributed to him in 1964 by another Conservative lawyer, the former science minister Lord Hailsham, in opposition to the new Labour government’s introduction of a Ministry of Technology.

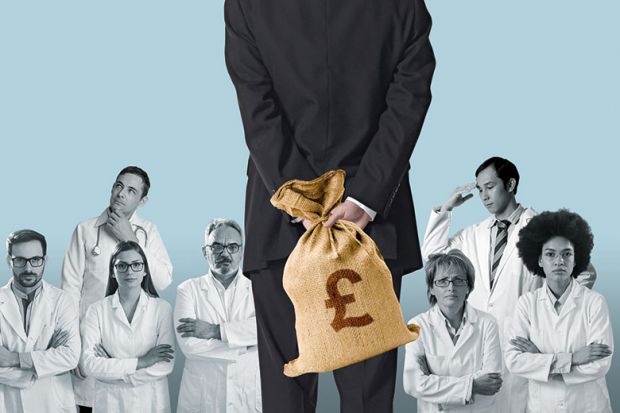

But, whatever its precise origin, and however imprecise its definition, the Haldane Principle has long enjoyed an iconic status among science policy experts, as attested to by the considerable coverage given to its supposed centenary last year – and not merely in the UK. The principle is brandished by scientists whenever they consider politicians to be getting too directive in their aspirations for the national science base – and even if they don’t retreat, politicians will typically feel the need to engage in enough semantic dodging and weaving to make a case that they aren’t actually in breach of the principle after all.

Nevertheless, in an age when governments across the globe are looking to science to fuel their knowledge economies and plug them into the so-called fourth industrial revolution of automation and artificial intelligence, the temptation for politicians to micromanage science and innovation is arguably as strong as it has ever been.

“I really think Haldane is dead – literally and figuratively,” says Philip Moriarty, professor of physics at the University of Nottingham. “The idea of government being kept at arm’s length from academia is just nonsense…Guidance from on high is trotted out with great regularity as a get-out-of-jail-free card by politicians with hollow promises.”

One particular flashpoint over recent years has been the impact agenda. When the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, in common with other UK research councils, started about 10 years ago to ask grant applicants to predict the real-world applications that their research would have, Moriarty’s became one of the loudest voices in opposition. The protesters complained that it was paradoxical to specify in advance what open-ended research would lead to, and accused the research councils of compromising science in order to pander to politicians’ desire for short-term returns on research spending. But the councils remained steadfast, insisting that they only wanted to see evidence that applicants had thought about the potential of their work and how it might be realised.

“I’m not naive – I understand the motives, and the reasons why,” Moriarty says, a decade on. “[UK] investment from industry in R&D was nowhere near as good as [in other countries], so universities have been made to pick up the slack and we are increasingly encouraged to seek investment from industry. But the upshot is that it is so much harder to get funding for basic research projects than it was 20 years ago. The balance has shifted completely.”

Over time, however, Moriarty’s views on impact have mellowed, and he admits to some sympathy with research councils obliged to find “a compromise between academic and political interests”.

“I do think they are doing well for it,” he concedes, “But the reality is that big grants get funded despite the system not because of the system. I baulk at the idea we should always have to think of impact statements in drafting a proposal...You shouldn’t be biasing your outcomes.”

The EPSRC went on to further Haldane-related controversy when it sought in 2011 to begin “shaping capability” in UK physical science by growing or contracting the amount of funding it made available to each subdiscipline based on an assessment of its strength, current capacity and an assessment of its “national importance”. But the irony of irate synthetic organic chemists (whose discipline was slated to shrink) lobbying the then minister for science and universities, David Willetts, for a change of heart was not lost on a politician who often publicly patted himself on the back for abiding by the Haldane Principle (the scientists argued that they weren't asking him to breach the Haldane Principle because EPSRC policies were determined by “civil servants in Swindon” rather than scientists).

Willetts’ successor, Jo Johnson, took up the baton, even going so far as to enshrine the Haldane Principle in law, making the UK the first country to do so. This came within the wider context of an industrial strategy that pledged significant boosts to R&D spending and the semi-merging of the research councils under a new overarching body, UK Research and Innovation, that many researchers feared would be an instrument of political influence (see box).

However, Johnson did not always receive the plaudits for his move that he might have anticipated, with critics arguing that university autonomy was already protected by historic royal charters. In a blogpost written at the time, Richard Jones, professor of physics and pro vice-chancellor for research and innovation at the University of Sheffield, noted that the proposed legislation establishing UKRI – now passed into law – says that “the Secretary of State may give UKRI directions about the allocation or expenditure by UKRI of grants received”.

Jones tells Times Higher Education that while he supports the Haldane Principle, there “needs to be greater clarity on what it actually stands for”. His blog noted that one interpretation would have it that science “should not be subject to any external steering at all, and should be configured to maximise, above all, scientific excellence”. But both he and Willetts agree that if scientists were left completely to their own devices, the focus of research would be very much imbalanced in terms of what gets funded – and where.

“Governments have a right – and more than that, a duty – to direct public funding towards areas of research that need focus, such as clean energy,” Jones says in his blog. And, speaking to Times Higher Education, Willetts cites UKRI’s Strength in Places Fund as an example of a legitimate means by which politicians can ensure that research spending is spread around the nation. According to UKRI, the fund is targeted towards “excellent research and high-quality innovation” that promises to have “a significant impact locally that closes the gap between that region and the best nationally”.

This approach reflects a view of Haldane as stipulating that, as Jones’ blog puts it, “at the micro-level of individual research proposals, decisions should be left to peer review, but…larger scale, strategic decisions can and should be subject to political control. Of course, in this interpretation, where the line of demarcation between strategic decisions and individual research proposals falls is crucial and contested.”

Willetts agrees that the definition of Haldane becomes “fuzzy when you come to the organisation of bigger projects”. But, for Jones, the main problem is that strategic decision-making in the UK is not transparent. “It ought to be a process that is inclusive, with voices from all sorts of organisations which [have] a vested interest – charities, NGOs and so on,” he says, adding that this was part of the promised ideal with the creation of UKRI. “But I am not convinced we have got it right yet – I certainly don’t understand how decisions are made.”

Wherever the precise line is drawn by Haldane on political interference, most observers agree that it was crossed by former Australian education secretary Simon Birmingham last year, when he secretly blocked the allocation of A$4.2 million (£2.3 million) by the Australian Research Council, overturning its funding decisions on 11 humanities projects. This incident, unearthed last year by THE, was a break with established protocol whereby Australian education ministers automatically agree to funding decisions made by funding bodies.

For Willetts, the episode provides a “clear warning” over what can happen when government intervention goes too far, and it makes the case for enshrining the Haldane Principle in law.

The principle “has become fundamental to the way in which we go about distribution of funding in the UK”, he says. "It certainly means ministers do not and cannot interfere. It would have been [impossible] to imagine what happened in Australia happening [in the UK] – though I am mindful that we must not become complacent.”

His view is echoed by Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg, a researcher development manager at the University of Sydney. However, the applied ethnomusicologist, who recently moved back to Australia after years working in the UK, notes that the autonomy offered by Haldane comes at the cost of additional bureaucracy to ensure that funds are being wisely spent. Most significant among the resulting mechanisms in the UK is the research excellence framework: a “mammoth, highly politicised” undertaking in comparison with its Australian cousin, Excellence in Research for Australia.

Enshrining Haldane in Australian law, she says, would require the nation to “implement policies, strategies and bureaucratic institutions”, which would entail significant and time-consuming “upheaval, consultation and bureaucracy”. For instance, “the ARC and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) would need to be managed by another, overarching organisation…policies and procedures would need to be much more aligned with other funding bodies, such as the Medical Research Future Fund, which are rather opaque in their application processes”. It would, in short, be “a huge undertaking”.

This perhaps explains that while Birmingham’s blatant interference in funding decisions “outraged arts, humanities and social sciences academics”, it “has not left people [in Australia] pining for Haldane”, according to Swijghuisen Reigersberg.

Nor is legislation on the cards elsewhere in the world. But that isn’t to say that the Haldane Principle has no traction there. East Asia is often perceived to be the region with the closest government direction of research: a condition of its rapid development in the post-war period. Singapore is a case in point. But while “nobody in Singapore will likely have heard of Haldane”, according to Barry Halliwell, a British biochemist who has spent the past 20 years working at the National University of Singapore, “if you asked them they would agree with the principle entirely”.

Singapore’s close historical ties to the UK and Europe mean that universities and ministers employ similar models of working, explains Halliwell, Tan Chin Tuan centennial professor of biochemistry and a senior adviser on academic appointments and research excellence to the university’s deputy president. “Academics [in Singapore] have freedom to do pretty much what they want, provided they can get the funding for it. There is a strong peer review element for research proposals, and the idea is that universities do more of the basic research and industry leads more of the applied research strategies.”

That balance has shifted recently, however. With no natural resources to trade on, Singapore faces particularly acute pressure to perform as a knowledge economy. Under its Research, Innovation, Enterprise 2020 strategic plan, published in 2016, the government has nominated various grand challenges and implemented some policy-led funds, in order, as the document puts it, “to allow greater flexibility in reprioritising funding towards areas of new economic opportunities and national needs as they arise over the next five years”.

This has prompted fears that research funding is tipping in favour of applied research. However, “in such a small country, there is a strong feedback loop”, Halliwell notes, and he was one of numerous academics to articulate the view to government that “universities were drifting away from basic research at their peril”. Strikingly, the politicians listened, and Singapore’s prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, made a speech earlier this year emphasising the importance of basic research.

Another Singaporean advantage, Halliwell adds, is the flexible nature of its research funding directives. “How much money goes towards which grants [is determined] in five-year cycles,” he explains. “The system is not rigid; experts are at the heart of decision-making and they have been known to make changes mid-cycle according to the demands of the community.”

Flexibility is enhanced by the fact that much of the research undertaken by universities is not publicly funded, but comes, instead, from the interest earned on the considerable endowments accrued by Singapore’s two main universities through donations from wealthy Singaporeans.

But the situation is very different in South Korea, where the government still maintains tight control of the research funding system. Last year, the country was reported to have the highest R&D spend to GDP ratio in the world, at 4.55 per cent, with a total budget of 78.8 trillion Korean won (£52.3 billion). But a significant proportion of that spending is dedicated to national development projects. According to Chang Kim, director of the Korean Association of Human Resource Development, the research budget for open call projects amounts to less than 10 per cent of the total.

Most of the publicly funded projects are run on a contract-style arrangement whereby researchers are actively recruited by the National Foundation of Korea to fulfil set goals. But even for non-directive projects, applicants must explain the national worth of their proposal, Kim explains, and receive a higher evaluation if it promises economic or industrial returns. “As a result, researchers are forced to concentrate primarily on research that can yield short-term results,” says Kim.

But rather than being a conscious clamping down on creative-led research, Kim suggests that “bureaucracy” is to blame here. “This is a problem that occurs when there are more ‘referees’ than ‘players’ in the field,” he says. But in recent years, campaigners have petitioned the government in the hope of expanding support for basic research, citing the UK’s Haldane Principle as an ideal.

“Many experts point out the fact that most research funding budgets are overly focused on large national research projects,” he tells THE. “Experts worry that if this phenomenon continues, the basic science ecosystem of South Korea will collapse. In this context, they argue that institutional arrangements are needed to enable researchers to carry out creative research without any government intervention”.

Kim believes that in a more “bottom-up funding system”, over which researchers had more control, “the autonomy and motivation of the researchers would naturally increase”.

Meanwhile, in the US, top scientists are charged with making funding decisions – but each decision must ultimately be signed off by both president and Congress, which presents problems when disagreements arise.

Politicians often have “an aversion to basic research”, according to John Holdren, reflecting on his time as Barack Obama’s chief scientific adviser. “The first problem is that a lot of people don’t understand that basic research is the seed corn to applied [research]. They want to argue that the National Science Foundation should only be funding research that has an immediate, tangible effect on the economy,” says Holdren, who is now Teresa and John Heinz professor of environmental policy at Harvard University.

That perception is one reason why, in 2016, the House of Representatives passed legislation dictating that NSF grants must be awarded only to projects seen to be in the “national interest”. Another reason is Republican antipathy to social science in particular. In 2013, for instance, the then chair of the House Science Committee, Lamar Smith, drafted legislation requiring the NSF to certify that every grant it awards advances health, prosperity, welfare or national defence. Smith also wrote to the NSF’s acting director demanding to see the internal reviews of five social science grant applications that he deemed of “questionable” value. The agency refused the unprecedented request.

Earlier that same year, House majority leader Eric Cantor successfully amended a spending bill to temporarily prohibit the NSF from funding political science unless it promoted US national security or “economic interests”. Cantor argued that it would be better for the NSF to focus on the natural sciences “to better focus scarce basic research dollars on the important scientific endeavours that can expand our knowledge of true science”. He also objected to several specific funded projects, such as one into why white working-class Americans vote for Republicans despite their espousal of economic policies that favour the wealthy.

Right-wing politicians' hostility to social science is not confined to the US, of course. Hungary's right-wing populist government recently banned the teaching of gender studies, for instance. It has also taken over the Hungarian Academy of Science's former role of financing research institutions, which critics fear could see funding for basic research slashed. In a February statement condemning the move, Academia Europa, the Pan-European academy, specifically called on the Hungarian government to "respect the Haldane principle of science funding adopted by most European governments (decision on science funding can only be made by researchers and not policy-makers)".

Back in the US, Obama pledged in a speech to protect “our rigorous peer-review system” to ensure that research “does not fall victim to political manoeuvres or agendas” that could damage “the integrity of the scientific process”. However, he added that it was important that “we only fund proposals that promise the biggest bang for taxpayer dollars”.

Although the end of the congressional session prevented the House bill from being taken up in the Senate, Holdren says that US scientists increasingly find themselves having to look for alternative sources of funding for basic research or projects on “unapproved” subjects seen as controversial by those in power. Examples include stem cell research, whose public funding was restricted by George W. Bush’s administration, and research into gun violence, whose funding had been severely restricted since 1996, before, in the wake of the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, Obama directed the National Institutes of Health to fund it (a programme that has now ended).

Moreover, Holdren adds, politicians’ decision to constrain research funding “lends itself to a degree of conservatism and cautiousness” within the peer review process itself. In a cash-starved environment, “reviewers have to have confidence that proposals will bear fruit, and that’s when you stop funding high risk, high return endeavours,” he says.

“Obama aspired to increase R&D spend to 3 per cent of GDP – with at least 1 per cent coming from public funding and the rest boosted through incentives for industry,” Holdren recalls. But while the administration “got a good start”, the House imposed a budget cap preventing the total federal spend from exceeding the existing budget.

That incentives were needed to boost industry spending is telling. Many observers believe that the perceived political push for research that yields predictable medium-term returns is bound up with the failure of many companies within the knowledge economy to invest enough of their own money in the research needed to keep them and their nations at the forefront of innovation – requiring the public sector to take up the slack.

For Nottingham’s Moriarty, “the private sector should be encouraged to dip its hand in its pocket a bit more”. And he urges governments to "trust scientists to do their jobs and trust industry to do theirs. True innovation does not come off the back of strict impact agendas.”

But he concedes that “some degree of impact must be shown” by university researchers; there should, in his view, be a “spectrum” of funding sources, with impact seen as a greater obligation for those signing up to do applied research.

However old the Haldane Principle might be, and whatever its precise meaning is understood to be, it is clear that it is not going to shield science from an obligation to forge prosperity from what, a year before Lord Hailsham's first mention of it, Labour prime minister Harold Wilson famously called "the white heat of technology". "Unless we can harness science to our economic planning," Wilson told Labour's annual conference, "we are not going to get the expansion we need."

And Jones, too, warns researchers not to use the Haldane Principle as an excuse to avoid seeking the application of their work. “Academia does need to accept the role of science,” he says. “The money does come from taxpayers. You do have a responsibility. We do need to think hard about translation of research and the motivation behind these goals.”

A fine balance: Futureproofing scientific autonomy

The Haldane Principle was enshrined in UK law in the Higher Education and Research Act 2017, which also established UK Research and Innovation. Although the act’s architect, Jo Johnson, was sacked from his position as minister for universities, science, research and innovation a few months after it was passed, Johnson defends the inclusion of Haldane in the legislation as a “protective mechanism” for scientists. That was particularly necessary given the impending publication of an ambitious industrial strategy White Paper pledging to increase productivity by raising the UK’s investment in R&D to 2.7 per cent of GDP by 2027, ultimately rising to 3 per cent.

“There was a lot of concern at the time that, given that the coming research bill would inform funding decisions for research councils in the future, if Haldane was not written into the legislation then power might be lost for UK scientists,” Johnson tells THE. “The last thing I wanted to do was to direct funding according to the latest Number 10 fad. From my point of view, this legislation was something I hope would prevent what we were beginning to see as a gradual erosion of the Haldane Principle.”

Johnson’s predecessor, David Willetts, had been criticised by some Haldane purists for announcing in 2013 that research capital funding should be concentrated on “eight great technologies”, while former chancellor George Osborne received flak for announcing a string of new research institutes concentrated on specific funding areas, such as graphene and data science. Concerns were also raised when Osborne announced in 2015 that the UK research budget would be expanded significantly with money from the Department for International Development, which, legally, had to be spent on foreign aid.

For Johnson, “the very notion of the industrial strategy” was something he “did not feel convinced by. I was concerned it was going to be nothing more than ministerial strategy playing to industrial projects. My concern was that ministers were simply not going to make that kind of [investment] without a compromise to the scientific research community.”

Asked whether he believes the current balance is right between directive and curiosity-driven research, Johnson says he “strongly believe[s] that any direction of research to meet policy aims risks destroying the value of science”. In his view, “the smartest thing to do is to get the largest possible amount of money and leave it to the good judgement of the research system. It is not the role of government to dictate what happens to that money.”

While he acknowledges it may be “too early to tell” whether his enshrinement of the Haldane Principle in law has been a success, Johnson dismisses any suggestion that he would have been better to rely on the existing royal charters to protect university autonomy as “complete bollocks”.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login