Everyone is waiting for it to rain at London’s Serpentine Gallery. This year’s Serpentine Pavilion, the institution’s great annual architectural unveiling, is a tree-inspired enclosure. Its one long wall, made of indigo-stained wooden slats formed into tessellated triangular units, curves around a courtyard only partially covered by a sloping, latticed canopy that, on a wet day, funnels the raindrops into small waterfalls.

The design, by German-based and Burkina Faso-born architect Diébédo Francis Kéré, is at once secluded and encompassing. The Burkinabe trees on which it is modelled are meeting places, in whose shade people gather. “I hope that everyone will feel invited,” Kéré has said in an interview. The sentiment is as simple as the design. But meeting places that truly encourage human beings to gather freely seem to me more remarkable than that simplicity suggests.

Perhaps I think this way because the university is a workplace that continually gathers and assembles people in the most mundane spaces. We come together for faculty meetings, library committees and exam boards in cramped campus rooms. We sit on stackable chairs – often within inches of a fire safety notice, a piece of chewed gum and a Blu-tack-flecked wall.

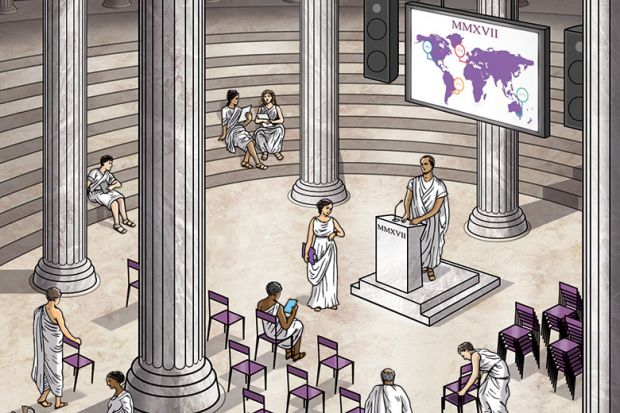

We also have other forms of meeting, which possess a greater figurative dignity. We meet for “roundtables” (never actually at round tables), speak on “panels” (reading at a desk) and attend symposia (with limited drinking, minimal partying and no togas). More novel and creative kinds of gatherings are given bewildering names such as “idea sandpits” or “research hubs”. Usually, though, such bold nomenclature signifies only a greater likelihood of multi-coloured pens and the sort of “ice-breaking” game in which many of us grow icier.

At this time of year, there is an understandable relief that most of our meetings are over for the summer. Now we can nestle into the bosom of a neglected research project and not have to look at an agenda again until September – or at least those of us who have not been lured on to the conference carousel can.

As some readers will already know, I am a lamentable sceptic about the kind of intellectual exchange that the tired conference format usually permits (“Conference season is here again”, Opinion, 9 July 2015). But last month witnessed an exception, with the launch of English Shared Futures, a discipline-wide effort to gather together teachers and researchers from across UK English studies. Initiated by the English Association and University English, the conference organisers anticipated 300 attendees. In reality, 600 turned up.

Our North American peers are more accustomed to such a disciplinary mega-meeting of the great and the good. The Modern Language Association’s annual convention – more commonly known as simply the MLA – is legend. It is a bustling hothouse of un-tenured teachers, pushy academic presses and imperious professors of the kind mercilessly lampooned by David Lodge in several of his campus novels. Luckily, English Shared Futures was a much kinder affair, sensitively geared to reflect more sombrely on the strength and scope of UK English studies. It included strong strands focused on teaching and early career academic development, and pointed sessions on sexual harassment and the experiences of black and minority ethnic academics.

By chance, English Shared Futures happened to be hosted in a rather remarkable venue. The Newcastle Civic Centre, designed by George Kenyon, is a stylishly mid-century monument to municipal modernism. Its 12-storey tower is capped with an iconic copper-faced lantern, complete with a crown of seahorses (a symbol of Newcastle’s seaport past), the blue lights of which are visible across the city at night. The adjacent council chamber, meanwhile, is an elliptical drum raised on cast-iron piloti in a generously landscaped courtyard with swooping bronze swan sculptures. Nine tall, steely flambeaux span the length of the entrance: a reference to the barrels of tar that used to be lit to draw residents to parish meetings. This is a place to meet indeed.

I am tired of meetings and roll my eyes with the best of them when reviewing the minutes, but there is something about the idea of an assembly that is different. Sometimes our disciplines are large and splintered: we are unused to seeing ourselves in the round. We suffer from the usual silos and subject-based separatisms. Gathering together doesn’t fix that. Nor does it ameliorate the problems we all face: growing casualisation and ever greater competition for funding and jobs. But it allows us to gauge the temperature and form new alliances; to recognise the collective state of a subject and the people committed to it. This is what assemblies do. They induce a kind of civic feeling.

At this time of year, we are less likely to be assembling than to be walking in a procession, watching graduates toss their caps. In her essay Three Guineas, Virginia Woolf cautioned against the merits of thoughtlessly joining “the procession of educated men”, insisting that we ask: “On what terms shall we join that procession? Above all, where is it leading us…?”

Assemblies, though, seem more benign. They ask us to witness our numbers and play our different parts but still sense our collective cause, so that we might at least make efforts to coordinate a shared future. The Prosecco at the procession is always nice, and there is no harm in messing around in an “idea sandpit”. But there is nothing like gathering together to ask who we are and where our collective endeavour should be directed.

Shahidha Bari is lecturer in Romanticism at Queen Mary University of London.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Assembly point

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login