Student debt has been big news in the UK over the past year. The Labour Party has promised to abolish it and anger over it fuels the furore over vice-chancellors’ pay that has led to the government’s review of university finance.

But it isn’t just students who are getting into increasing debt in the modern world of marketised higher education. Amid all the headlines in December about excessive retirement pay-offs, it would have been easy to miss the University of Oxford’s £750 million bond issue: the largest yet by a UK university and more than double the £350 million that its rival, the University of Cambridge, raised in the same way in 2012 – albeit with a repayment period of 100 years, as opposed to 40.

Although a £70 million bond issue was launched as long ago as 2000 by Keele University, 2012 was the first year of the current wave of UK bond issues, kicked off by De Montfort University’s £110 million, 30-year issue. Other universities to have since taken the same path include Cardiff University (£300 million; 2016; 39 years) and the universities of Southampton (£300 million; 2017; 40 years), Leeds (£250 million; 2016; 34 years), Liverpool (£250 million; 2015; 40 years) and Manchester (£300 million; 2013; 40 years). In contrast, no bonds at all were issued between 2008 and 2011 by UK universities.

This recent opening of the floodgates potentially raises questions for universities’ future viability. UK institutions are already struggling to cover the increasing costs of their pension liabilities; their plans to abolish the Universities Superannuation Scheme’s defined benefits approach have led to a recent series of high-profile strikes by university staff. Could the increasing cost of servicing debt put a further cat among the financial pigeons?

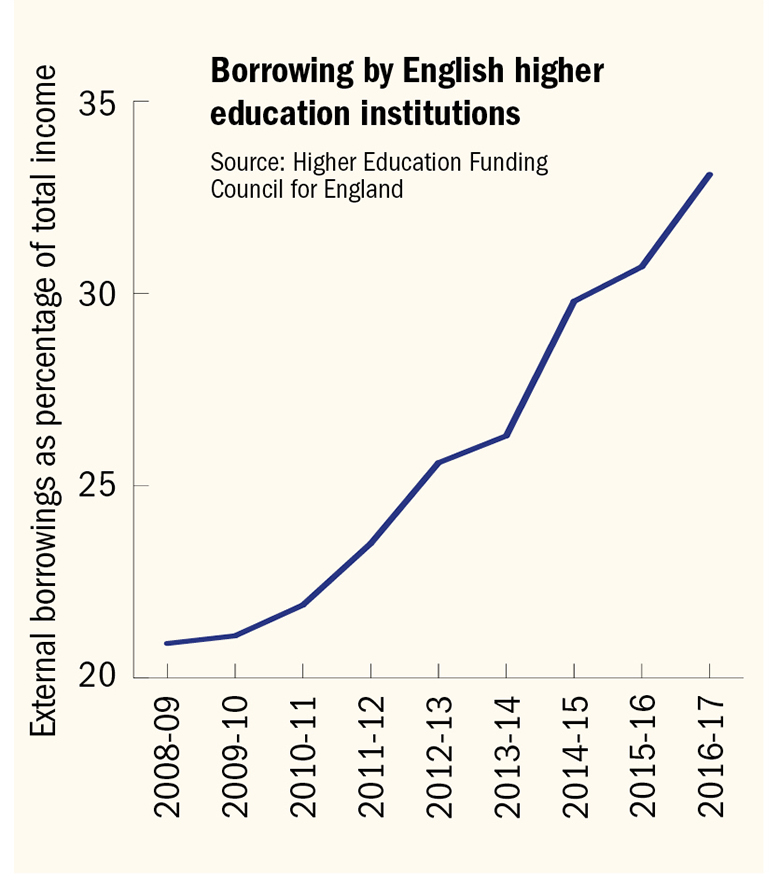

Overall, debt levels are certainly rising. UK universities’ external borrowing as a percentage of their income rose from 29.8 per cent in 2014-15 to 31.2 per cent in 2015-16, according to the most recent Financial Health of the Higher Education Sector report from the Higher Education Funding Council for England. In 2010-11, it was just 21.9 per cent.

Borrowing by English institutions 2008-2017

Data for the US are patchier than for the UK, but they also paint a picture of rising debt: in the decade to 2013, public university and community college debt more than doubled, to $151 billion (£109 billion), according to a 2016 Socio-Economic Review paper titled “The financialization of US higher education” . And bonds account for a significant chunk of that figure. As long ago as 2009, higher education bond sales in the US totalled $35 billion, according to newspaper The Bond Buyer. Indeed, bond finance is so well established in the US that when Harvard University launched a $2.5 billion issue in 2016, it scarcely raised an eyebrow.

In Australia and Canada too, institutions including the universities of Sydney, Melbourne and Ottawa, as well as Toronto’s Ryerson University, have launched large bond issues in recent years.

So what is behind this borrowing boom? The very low interest rates that have endured since the financial crisis of 2008 mean that pension funds and other institutional investors have been keen to find a long-term home for their capital, explains Luke Reeve, a partner at EY specialising in capital and debt advice. Hence, they have been increasingly happy to lend to universities. Meanwhile, rules brought in since the crisis have made it uneconomical for banks – traditional lenders to the UK sector – to offer longer-term loans, Reeve adds, leaving universities with little choice but to issue bonds if they want to compensate for falls in state capital funding.

Universities in the UK and Australia have also been encouraged to compete for students, and so have started constructing new buildings to wow potential applicants on open days. According to Julie Mercer, head of education and a partner at Deloitte UK, British universities are engaged in an “arms race”: a phrase that pops up repeatedly when you speak to figures closely involved in university borrowing. “If everyone else is investing in new facilities and you’re not, it’s very hard to hold your nerve and decide that, actually, you probably shouldn’t,” she says. “If everybody else is creating bigger, shinier, higher-quality, more innovative facilities, it’s hard not to get involved in that as well.”

This phenomenon is very familiar in the US, where campuses are competing with each other to build luxury dormitories, complete with swimming pools and climbing walls, according to Charlie Eaton, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of California, Merced and one of the authors of “The financialization of US higher education” paper. At the beginning of 2017, for instance, the University of Miami announced that it would spend $155 million on a 1,100-bed dorm complex, including a 200-seat auditorium, a “curated warehouse” for exhibitions and plays, “outdoor recreation decks” and a bike room.

And, it seems, such investments can pay off. One study of US student choice, “College as country club: do colleges cater to student preferences for consumption?”, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2013, found that wealthier students typically do choose their universities on the basis of “consumption amenities” on campus, as opposed to “academic quality”.

Not all university debt relates to luxury student facilities, however. Oxford’s bond issue is motivated by “research and education”, according to David Prout, pro vice-chancellor for planning and resources at the institution, with a larger “strategic goal” of remaining “at the highest levels in terms of world rankings”.

Moreover, those who work with universities to raise capital emphasise how prudent higher education institutions remain. EY’s Reeve, for instance, reports that their boards offer more scrutiny of debt plans than those of any other type of institution that his firm advises. Nevertheless, it does appear that university leaders are becoming more comfortable with debt. Marc Finer, director in KPMG’s debt advisory group, says that some vice-chancellors have concluded that “doing nothing is the more risky option if we [want to still be] around for as long in the future as we have been in the past”.

And defenders of borrowing often argue that universities should take their chance to invest in the future at a time of historically low interest rates – an argument not dissimilar to that made by UK Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn in favour of increased state spending funded by borrowing.

The ultimate test of financial prudence, of course, is whether debts incurred can be repaid. In universities’ case, that will depend largely on income from student fees. And while the rise of robots and artificial intelligence might raise long-term questions about universities’ role in a potentially diminishing labour market, few see student numbers dipping significantly any time soon.

“The global demand [for higher education] is enormous and UK universities have seen that,” says EY’s Reeve. “Statistically the demand is there…On an investment basis [borrowing] doesn’t look unwise.”

And the ratings agencies, which assess borrowers’ creditworthiness, agree. “Higher education continues to be a necessary credential in order to get a good job. In fact, higher levels of higher education are increasingly necessary to advance in the workforce,” says Susan Fitzgerald, associate managing director for global higher education at Moody’s.

But the assumptions underlying all this optimism do at least seem open to question. The most important one relates to student numbers.

“Most sets of forecasts that I see from universities are on the basis of student numbers increasing. Very few universities are standing still,” says Philip Stephenson, a director in Grant Thornton’s debt advisory team. But he points out that “not everybody can grow; there’s got to be a tipping point where the growth stops or stagnates”.

Anti-immigration rhetoric and policies in the West could, for instance, see the number of high fee-paying international students start to contract. There have already been signs that international students are less likely to take up places in the US after the election of Donald Trump as president, and EU student applications to the UK fell by 7 per cent in the first application round since the Brexit referendum in 2016. Indeed, when Moody’s issued its AAA credit rating for Oxford prior to its bond issue, it noted that “unlike many of its Russell Group peers”, the university’s strategy “is not reliant on growth in student numbers”.

For Stephenson, such worries should not prevent universities from borrowing because “standing still is also not an option, as the expectation of discerning students continues to rise”. But Howard Bunsis, a professor of accounting at Eastern Michigan University who has visited dozens of US universities to analyse their finances, is wary of the “build it and they will come” attitude taken by many institutions, describing it as “a tremendous gamble”. And, back in the UK, such worries have come to the surface at UCL, where there is discontent over a planned £1.25 billion expansion into East London. In early February, a formal investigation was launched into whether academics’ warnings about the project’s “serious financial and academic risks” have been properly scrutinised.

The looming end of the era of super-low interest rates could also slow the borrowing spree. Although existing borrowers have, to an extent, “locked in” the low rates to their repayment schedules, future rate rises could leave others less able to afford capital. Hefce warned in its most recent financial health report that “a rise in interest rates could add significant costs, placing increasing financial burden on individual institutions’ sustainability if not well managed”.

Political risks also exist. Several years ago, for instance, the University of California system took advantage of its high Moody’s credit rating to borrow large amounts of money to repair buildings, fund pensions and construct new buildings, including a $937 million bond issue in 2011. According to Merced’s Eaton, that rating was predicated on the assumption that the institution had the “market power” to raise fees.

“That ended up being completely wrong,” he explains; in 2012, the state halted tuition fee increases and forced universities to take more in-state students, prompting Moody’s to downgrade the university’s outlook from “stable” to “negative”. Something similar could happen in the UK, too, Eaton thinks: “Imagine if you have a Corbyn administration that says: no more tuition [fees], ever.”

His wider point is that “a financial-market-based approach to capitalising universities is very problematic because the university is providing a public good, so there’s a public expectation of how it will be provided, which can run up against the financial markets”.

What happens if universities struggle to repay their debts? So far, headlines about bankrupt or distressed universities are scarce. But one famous example from the US is Cooper Union, an arts, architecture and engineering university in New York City that has historically been free to attend. It sparked student protests by introducing tuition fees in 2013, citing financial difficulties; one of the reported reasons was the unaffordability of a $175 million loan it took out in order, in part, to fund a showpiece new engineering building.

Working with distressed colleges is “unfortunately a growing line of business”, says Larry Ladd, director of Grant Thornton’s US higher education practice. He has worked with several institutions over the past year that have closed because they could not pay their lenders. But he makes the point that when universities do get into trouble, it’s often too simplistic to blame their debts. In many cases, “the college would have gotten into trouble earlier if it hadn’t borrowed money”, he argues. “I never believe that debt is the source of these distressed colleges’ problems.”

What happens to a university in distress, and the amount of financial scrutiny that it faces in general, depends on the type of borrowing it has undertaken. Public bonds, such as those raised by Oxford, are used for the very biggest sums; Barclays estimates that the minimum size of a public bond is about £250 million. Public bonds are sold on the open market and can be traded openly. They also require a public credit rating from an agency such as Moody’s, and some have attached covenants: financial conditions such as a threshold level of income versus debt that, if breached, can trigger an intervention from the lender.

Oxford’s bonds have no covenants, which Prout says is “pretty normal” for university issues. But although highly trusted institutions can issue bonds with few strings attached, they still have to worry about their credit ratings. Oxford’s AAA rating is “essential”, Prout says, and the university would not put it in jeopardy by borrowing too much.

“We are looking at the creditworthiness of the university over the next two to three years,” explains Jeanne Harrison, a senior analyst for the specialist agency Moody’s Public Sector Europe. Rating agencies look at the “intrinsic strength” of a university’s finances, but also form a “qualitative judgement” on whether the government would step in if it got into trouble, she says. The current policy in England is that “market exit” will be permitted. But “from our perspective, we think that [policy] is more likely to impact the newer, financially weaker players” than the more “established” institutions, she adds.

In contrast to public bonds, private placements are typically smaller issues, restricted to a single institution or group of investors, such as pension funds or insurers. “This is private lending, like bank lending, but it’s not banks who are doing it,” explains KPMG’s Finer. In May last year, for example, the University of Bristol announced that it had raised £200 million to build a new campus from the US-based Pricoa Capital Group. And in March, the University of Portsmouth revealed that it had raised £100 million from “two North American institutional investors”, in order to support “estate development”. According to the Financial Times, Lloyds Bank estimates that private placements account for about half of the £3 billion borrowed by UK universities on the capital markets since 2016.

In these arrangements, some institutions are permitted to pay merely the interest until the debt matures after the specified period, according to Finer, whereas others will be obliged to hold “substantially more cash than [they] require” and to have “wiggle room in their business to underperform without compromising the lender’s confidence that it will get its money back”.

There may also be restrictions on how money raised via private placements is used, as well as “oversight by lenders of how the capital programme is progressing relative to the plan”. Lenders won’t sit in on board meetings, but may require accounts and budgets of capital projects, Finer says. “It’s not overt control – it’s just that you’ve got a stakeholder in the business that you need to manage more intensively [than with a public bond].”

If a university breached a covenant, it would be required, as a first step, “to hire a financial consultant to help it improve its financial condition”, explains Grant Thornton’s Ladd. But if problems persist, some lenders will bring in “workout specialists”, who “tend to be a lot more directive” and can say to a university: “Time to slash personnel by 10 per cent. Do it. You have six months”.

Still, Ladd and several other financial experts point out that lenders are likely to take a relatively lenient approach with universities compared with other borrowers because no bank wants to be held responsible for shutting a campus: that would be a “very bad public relations move”, Ladd notes.

There is one thing that university debt bulls and bears agree on: more borrowing is likely to increase inequality between institutions.

For a start, smaller, poorer universities find it much harder to raise money. EY’s Reeve says that he recently had to advise a client not to go through with an attempt to raise debt capital since its revenues and value of estate were simply too low compared with the size of the loan that it sought: “They just don’t have the credit quality,” he says.

There are also inequalities in terms of the strings attached to loans. “Riskier institutions” that do manage to borrow money will be subject to more restrictions on “how they run their business”, Finer points out.

And lower-ranked institutions will bear the brunt of an overall reduction in student numbers, points out Grant Thornton’s Stephenson. If applications fall, “where someone might have historically gone to a medium-tariff university, they may now have the option of going to a high-tariff institution, due to that university’s having space”, he says, causing the medium-tariff institution to accept students that would previously have gone to a lower-tariff institution. The latter have nowhere to turn to make good their losses.

Smaller institutions that can’t raise money to build the facilities that students expect “are stuck between a rock and a hard place, as they need capital to remain competitive with their peers, but struggle to borrow because of their asset base or reputation”, Stephenson says. But those with a “niche offering” that are seen as “best in their class” can still be successful. The key is “sustainable investment, which [provides] capital expenditure to remain competitive…at a pace that is affordable for the institution”.

At the other end of the scale, the very richest private US universities, blessed with endowments in the tens of billions of dollars, are now behaving more like lenders than borrowers, according to Merced’s Eaton: “There’s a joke that Harvard is a hedge fund with a university attached.”

According to “The financialization of US higher education”, the richest 1 per cent of US private universities made nearly $38,000 more per student annually from their endowment fund returns than they paid out to service their own debts. But why would an institution such as Harvard need to go into debt at all? The answer is that instead of spending its endowment – which has roughly achieved a 10 per cent annual return for three decades – Harvard issues bonds instead at interest rates nearer to 3 per cent, explains Eaton. Because lenders to tax-exempt institutions do not have to pay tax on the interest that they are paid, they are able to charge universities even lower interest rates, he explains.

As his paper puts it, “by leveraging their strong credit ratings, wealthy institutions could use inexpensive debt to effectively maximize their overall financial returns”. Harvard is now increasingly financing the costs of educating its students through investment returns on its endowment, rather than through fees, Eaton adds.

The picture is very different outside the elite, where institutions do not have the critical mass of capital to play a similar game. Below the richest 10 per cent, US public universities pay out about $200 per student more in interest per year than they earn from their endowments, his calculations find. He worries that such universities have been led into difficulties by vain attempts to emulate the likes of Harvard “without having an equivalent financing model” – and he adds that that fear also applies to borrowing by UK universities, including Oxford and Cambridge.

Oxford’s Prout insists that UK levels of debt are still “nowhere near” those of the US. And even though, for all its recent efforts, Oxford’s endowment is still dwarfed by those of many of its US competitors, it does receive 40 per cent of its revenue from Oxford University Press: a “reliable source of income…which partially mitigates the risk of domestic policy volatility”, according to the small print of its Moody’s rating.

Whether or not university bonds prove to be wise investments or reckless gambles, one thing is clear. Something about the sector has changed significantly when arguably one of the best sources of information about universities’ finances and future prospects is a credit rating agency.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Going for broke

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login