How can we imagine a new university?

In this existential moment for higher education, the corporate university is not the only end point possible – we can imagine so much more. David J. Staley offers 10 new ways of thinking about universities, in this excerpt from his book ‘Alternative Universities: Speculative Design for Innovation in Higher Education’

The university is more – much more – than simply a transactional exchange: I pay you tuition, you certify my skills. In the German university as enacted by [Wilhelm] von Humboldt, one left the university a different person, transformed into a disciplined subject. The threat posed by the external environment in the German case was indeed an existential one: Could the university continue to exist in its present form given the changes occurring in the external environment?

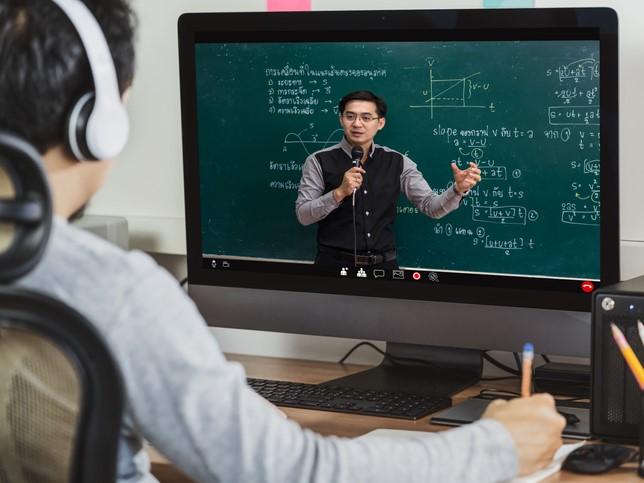

I would submit that truly disruptive innovation in higher education comes with changes in the nature and purpose of those transformative experiences. Too many examples of what passes for innovation in the 21st century – massive open online courses (Moocs) especially – focus on transactions, on questions of delivery. Anyone seeking innovation in higher education today should concentrate on the kind of transformational experience it enacts.

The problem is not that universities are lacking in innovation, but rather that they suffer from a poverty of imagination of what that innovation might be. “This is an existential moment for universities,” writes the philosopher of higher education Ronald Barnett. “All systems of higher education across the world are moving inexorably in the direction of the marketised university. Consequently, the pool of ideas through which the university is comprehended is shrinking.” Indeed, the main existential crisis facing the university is a poverty of ideas about what universities can become. We must look elsewhere, more broadly and with greater imagination, for potential sources of innovation.

- Because you’re worth it: how universities can prove their value to prospective students

- Lifelong learning resources

- The campus is dead, long live the campus

Against this background, the questions arise as to what, if any, are the prospects for imagining the university anew? What role might the imagination play here? What are its limits and what might be its potential for bringing forward new forms of the university? This, then, is the problem before us: the place of the imagination in developing the idea – and the institutional form – of the university.

Part of the hopelessness about the future of universities is not only because of the paucity of fresh ideas, but because the ideas that are publicly discussed “are being driven forward with such determination that it may appear that ‘there is no alternative’”. For Barnett, there are indeed alternatives, if we only imagine the possibilities. He urges us to employ our imaginations productively to generate “a proliferation of ideas of the university”, as it “can show that the corporate university, the entrepreneurial university, the marketised and the bureaucratic university are not the only available representations of the university”. His observations highlight the degree to which the presumptive Moocification of higher education represents only one future path, one direction that disruptive innovation might – or must? – take. Barnett, instead, asks us to consider multiple possibilities. There is a wide variety of possible innovations, especially around reimagining the purpose of the university itself.

In this book, I have taken up Barnett’s challenge and employed my imagination to generate ideas about future forms of the university, alternatives both to our current practices and to the narrowly defined, technologically delivered university. What follows are 10 feasible utopias; I believe that each has the potential to be enacted, and I fully expect to found all of these as fully realised, actual universities.

- Platform university: organised and managed organically through the unregulated interactions between teachers and students

- Microcolleges: made up of one professor and 20 students

- The humanities thinktank: scholars from humanities disciplines produce research to inform policymaking

- Nomad university: a university that shifts location every year, offering a series of gap-year experiences

- The liberal arts college: instead of being based around subjects, learning is based around skills – for example, complex problem-solving, imagination, leadership and others

- Interface university: students learn alongside artificial intelligence, rather than using it as a tool

- The university of the body: information now arrives via all of the body’s senses – students will be given the literacy skills necessary to decode this data

- The institute for advanced play: generating new and novel knowledge through creativity and imagination

- Polymath university: students major in three different disciplines – one of the sciences, one of the arts or humanities, and a professional discipline – in order to master the three main habits of mind

- Future university: students are taught to visualise the future in order to better design and build that future.

For these ideas to become reality, we would very likely need to create a new institution, rather than expect to redesign or reorganise an existing organisation, since resistance to change is endemic in higher education. Another obstacle in the realisation of these speculative designs is that there seems to be little appetite for developing universities that deviate so dramatically from the norm. Institutions of higher education are keen to benchmark other universities, emulate their peer institutions, and, as a result, all look alike. In such an environment, innovation that seeks to create new transformative experiences appears risky and quixotic. Barnett calls for nothing less than a new poetics of the university. Poets “imaginatively [bring] into being new worlds”, chiefly by employing metaphor. “The creation of new metaphors through which to comprehend universities, therefore, is one of the most powerful acts of the imagination.”

He asks, “Can we develop a practical poetry…of the university?” I have taken up the challenge that Barnett has announced to university presidents, vice-chancellors and other higher education leaders: they “should become poets of the university, coming forward with new languages, new metaphors for understanding the possibilities”. Faculty are not excluded, of course, in as much as they are able to exercise some control and influence over the future direction of the university. But Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, raises the question of the locus of creativity. “Has it shifted from the academic disciplines to the institutional agency of the university, and from the research professorate to the university executives? Are very bright people increasingly drawn to quasi-entrepreneurial roles at the head of these organisations?” This book specifically addresses the “very bright people” engaged in university strategy, for that group is involved in what Marginson calls “university-making”. “University-making and space-making have become creative activities in their own right, practised by multi-performing university leaders who draw on a portfolio of qualities and roles, from business entrepreneur to scientific boffin to patron of the arts. Sometimes they are artists themselves of a kind. Most are timid. Some are bold. A few make changes that reverberate through the university world. These university leaders are supported by teams with an assemblage of specialised skills. Yet much rests on their own ‘animal spirits’ and visioning.”

My sense is that Barnett’s call for more “practical poets” is aimed at the university presidents, higher education policy experts, corporate executives and entrepreneurs whose university-building has been imaginatively impoverished and imitative. The speculative designs presented here are in the spirit of the great university-makers of the past, such as Humboldt, John Andrew Rice (the founder of Black Mountain College), and Lucien L. Nunn (the founder of Deep Springs College). These 10 alternative universities might be understood as practical poems about the future of the university.

David J. Staley is an associate professor in the department of history at Ohio State University.

Adapted from Alternative Universities: Speculative Design for Innovation in Higher Education, by David Staley, copyright 2019. Published with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.