Decolonising medicine, part one: taking the first steps

Decolonisation should not be limited to arts and social sciences, but many struggle with how to apply it across STEM disciplines. In her first resource, Musarrat Maisha Reza shares advice on effective approaches to decolonising medicine

The rising interest in diversifying the curriculum and making it more inclusive comes alongside a lack of understanding of its application in medicine. Tools to decolonise the medical curriculum are scarce.

Discussions with fellow academics in the UK have revealed a perception that decolonisation is more relevant to the arts and social sciences. Medicine has been perceived as “black and white” knowledge with little room for opinions or perspectives. I have heard questions over whether decolonisation of science is relevant because “DNA is DNA” and we cannot change that.

Making sense of decolonisation

In a 2014 paper, Heidi Safia Mirza of Goldsmiths, University of London highlighted how complex exclusion is in higher education with intersecting factors such as class, gender and race at play. She pointed to how Black and ethnic minority women are often treated as “gendered, raced, classed, colonised and sexualised others” in systemic structures of power and dominance.

- Resource collection: Decolonising the curriculum

- Why is self-reflection core to decolonisation and anti-racism in the academy?

- Are STEM admissions processes hindering our diversity efforts?

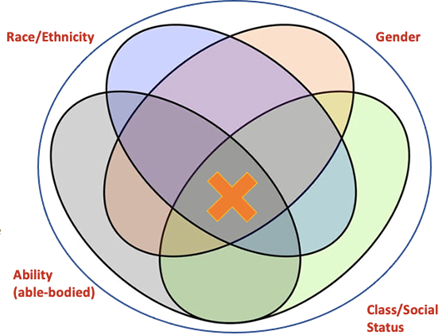

I have tried to make sense of decolonisation and how my intersectionality and lived experiences impact my understanding. Figure 1, below, offers a simplified representation of how I perceive and explain decolonisation. The large blue circle encompasses the concept of decolonisation. I have broken it down into an intersecting Venn diagram and labelled each oval with a specific social identity, such as gender, race and ethnicity, class and disability.

Some individuals are marginalised by one or two factors within a structure that enables white privilege, whereas others embody multiple identities resulting in greater and more complex intersections and discrimination. The orange cross represents someone whose identity embodies all the different social factors labelled in this diagram and the deeper we dive into the intersections, the more excluded their voices become in a society structured to position the white, middle-class, male, heterosexual, cisgendered and able-bodied person in the place of highest privilege.

When applied to a colonised curriculum, my aim would be to dismantle the power hierarchy that upholds this discriminatory structure within academia, such that the individual represented by the orange cross has equity in power and voice.

Keeping this in mind, I developed a decolonisation of medicine module. While such a specific module might risk tokenising decolonisation, it also helps to provide a smoother segue into decolonisation within medicine by raising awareness of the topic and getting both staff and students to think about it critically.

In a series of resources, I will share tips for anyone considering creating their own module focused decolonising medicine, with lessons that are transferable across many other disciplines.

Allow space for objectivity alongside personal viewpoints

Discussions will inevitably arise about past medical atrocities that have resulted in injustice and oppression. Examples include the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which Black men were untreated for syphilis to study the progression of the disease, or the Willowbrook hepatitis study, in which mentally disabled children were experimented on to discover the hepatitis vaccine.

- Be comfortable with opposing viewpoints: It is challenging to take a step back and allow students to understand the “other side”. Unjust practices such as these were once deemed ethical and allowed by people in power. It is important to push students and tutors to investigate why this was accepted and what could be the arguments in favour of such injustices that enabled them to take place.

- Create safe spaces for discussion: There will be reluctance to speak in favour of what we deem unethical today, for fear of looking bad. It is, therefore, essential for tutors to create safe spaces for robust academic discourse. Debate questions such as “Did the Willowbrook hepatitis experiments on the intellectually disabled children bring about more overall good than harm?” to nudge students to expand perspectives and employ an objective thought process.

Embed intersectionality in the syllabus

Decolonisation cannot be discussed without highlighting intersectionality. It is important to show students how the process of colonisation has created structures of oppression not just for other-than-white people but for people with disabilities, women, people from the LGBTQ+ community, or those who do not belong to the upper middle or upper class. Try to touch on a new aspect of intersectionality every week to provide a broad picture.

For example, in the week Tuskegee syphilis trial is discussed, we discuss Black men of the working class. During discussions about Willowbrook, we highlight children with disabilities. In another workshop, we discussed Puerto Rican women and reproductive rights, touching on ethnically minoritised women in the Global South. This demonstrates that decolonisation is not just an issue for one specific group but rather a mission for everyone.

Musarrat Maisha Reza is senior lecturer in biomedical sciences at the University of Exeter.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

Additional Links

Read more from Musarrat Maisha Reza on decolonising medicine:

Decolonising medicine, part two: empowering students

Decolonising medicine, part three: uncovering the full picture with silenced voices and histories