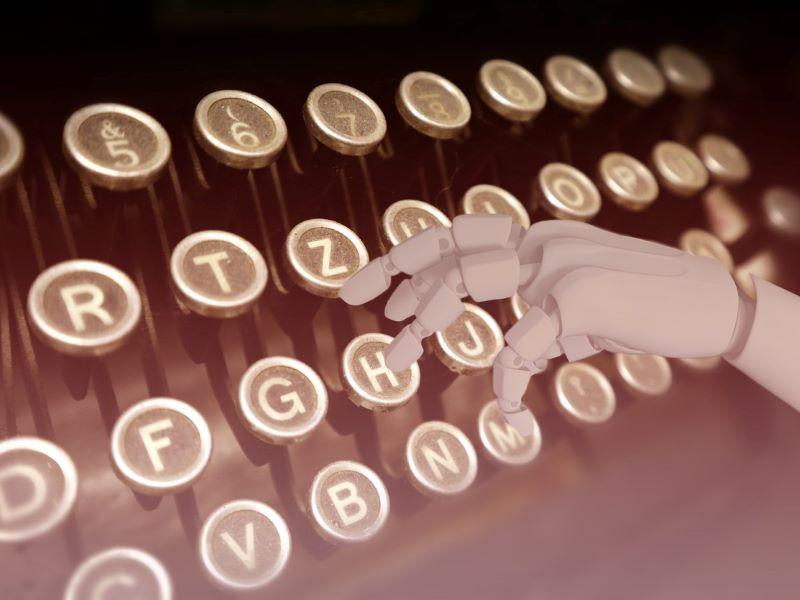

ChatGPT and AI writers: a threat to student agency and free will?

If we resign ourselves to thinking that resistance is futile and allow AI to replace students’ voices, we are surely guilty of abandoning our responsibilities as educators

A great deal of ink has been spilt recently following the launch of ChatGPT and the advent of AI that can generate text and answers of a sufficient standard to be used by students in their assignments. Responses, in my opinion, have thus far been rather predictably, if not troublingly, conformist.

Writers here in THE and elsewhere have variously suggested that if we can’t beat it, we ought to join it and that hybrid or asynchronous communication ought to be embraced and integrated as part of the brave new world of human-machine creativity. More informal discussions with colleagues have suggested that resistance seems futile and that we ought to embrace AI to equip students to operate in a hybrid world of the artificial and the real for the purposes of employability. Some slightly more ambitious voices have suggested that AI-generated assignments make the case for authentic assessment or a more “human” form of assessment even more urgent, but how this might transpire in ways other than falling back on the adage of assessment for learning, constructive feedback and alignment with skills seems less clear.

- ChatGPT has arrived – and nothing has changed

- ChatGPT and the rise of AI writers: how should higher education respond?

- Eight ways to engage with AI writers in higher education

For me, the resignation (often couched as embrace) I hear from some quarters is rather worrying, both educationally and politically. Whilst I’m not predicting, as some have speculated, that AI will render us (like many other professions) obsolete over the next few years, what I suggest is at stake here is that the use or acceptance of AI in assessment actually runs counter to (1) our mission as educators and (2) to the avowed aim of many institutions to produce graduates who not only possess critical literacies but are able to make a meaningful and positive contribution to society.

In essence, the embedding of AI (notably ChatGPT and its inevitable successors) in our teaching and assessment will erode student autonomy over their learning experiences, disenfranchise independent thinking and ultimately nullify freedom of expression.

My own research has illustrated conclusively that students worry about writing assignments that comply with academic conventions while also having to navigate learned behaviours and strategies fostered through prior assessment practices (the highly prescriptive, assessment objective-driven nature of A level, BTEC and Access assessments, for example).

However, given that writing (the predominant mechanism for assessing students) derives from the retrieval and reconstruction of ideas within the self, I have argued that assessment inevitably has an emotional backdrop – which Stephen King in his On Writing: A Memoir of a Craft has aptly characterised as “fear” or “timidity”.

In our students, this often manifests itself in problems forming and articulating an argument that not only does justice to one’s ideas but conforms with the marking scheme. In other words, students often find it difficult to express themselves, to find and articulate their “voice”, through which they can (a) learn (writing as learning) and (b) demonstrate attainment.

This is complex, emotional work, which takes place under the gaze and scrutiny of a marker and in the midst of both the massification of participation and a plethora of other voices (critics, theorists and the like). But what happens if the struggle to articulate one’s voice is delegated (even in part) to AI? Surely this further deprives the student of the opportunity to participate meaningfully in the dialogic nature of learning, critical thinking and academic discourse?

Granted, some have suggested that ChatGPT could be usefully deployed as a tool for overcoming writer’s block, but inevitably some students may be happy to farm out much or all of this work to AI given the much-publicised downturn in engagement (exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic) and the increasingly instrumentalist approach many students display toward learning and assessment. But if we resign ourselves to thinking that resistance is futile and merely allow AI to partly or wholly take the place of the students’ voice and the complicated learning process that goes into fulfilling an assessment task, we are surely guilty of abandoning our responsibilities as educators (assuming that we subscribe to Freire’s notion of education as an “activity of freedom” and Nussbaum’s conception of education as foundational to human development).

Indeed, if we allow AI to increasingly subsume the voice, agency and, ultimately, thought of our students, how can we expect them to go out into the world and participate meaningfully in debates and democracy itself? Not only can it be argued that they will lack the necessary skills to synthesise, evaluate and present arguments autonomously (because AI has done it for them and is being promoted as a tool for doing so) but AI will also have subsumed their free will.

Current assessment methods are of course far from perfect and need to be more meaningfully authentic, but at least they involve human participation and agency. If the very process and vehicle for recording and managing information is increasingly dehumanised, where does that leave us? With the disenfranchisement of our students being accelerated – and ultimately having hastened a vicious cycle of increased disengagement, producing graduates who are dehumanised, alienated and depoliticised as they lack agency and their own voice.

One way we could address these problems is to reimagine university assessment as dialogue – especially in respect of academic writing. We seem to have strayed from the original Socratic notion of argument, learning and student support as dialogue, toward the type of discourse Socrates identified in Gorgias as belonging to the sophists (argumentation).

Most marking criteria seeks to test both evaluation and argumentative skills, but we often interpret this as meaning presenting a persuasive, convincing written argument. This is not necessarily true evaluation and, too often, evaluation is sacrificed on the altar of rhetorical intent.

What I suggest ought to be assessed (and which helps us navigate some of the issues posed by ChatGPT) is a record of the student’s personal, but academically justified, reflections, arguments, philosophising and negotiations. Student work would then be a genuine, warts-and-all record of the process of learning, rather than the submission of a “performative” product or “right argument”, as one of the students in my research so aptly put it. This would enable our students to become better thinkers.

Such an approach would be inclusive, personalised, flexible (its adaptability would make it perfect for aligning with Universal Design for Learning) and encourage students to become critical and reflective thinkers while fostering the “human” skills we often tout as being key for employability. Reflective, dialogic writing offers a way forward for working with and around AI-generated writing while placing agency and learning back where it belongs – in the hands of our students.

Like many of my colleagues, while I’m not sure we can actually fight AI, I do believe it is our duty as educators to resist or curtail it’s potential to further erode student agency, even if that means finding innovative, more dialogic ways around it. As George Orwell recognised, language has the power to “corrupt thought”. As such, we allow AI to displace our control of language at our peril.

Adrian J. Wallbank is lecturer in educational development at the Oxford Centre for Academic Enhancement and Development, Oxford Brookes University, UK.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.